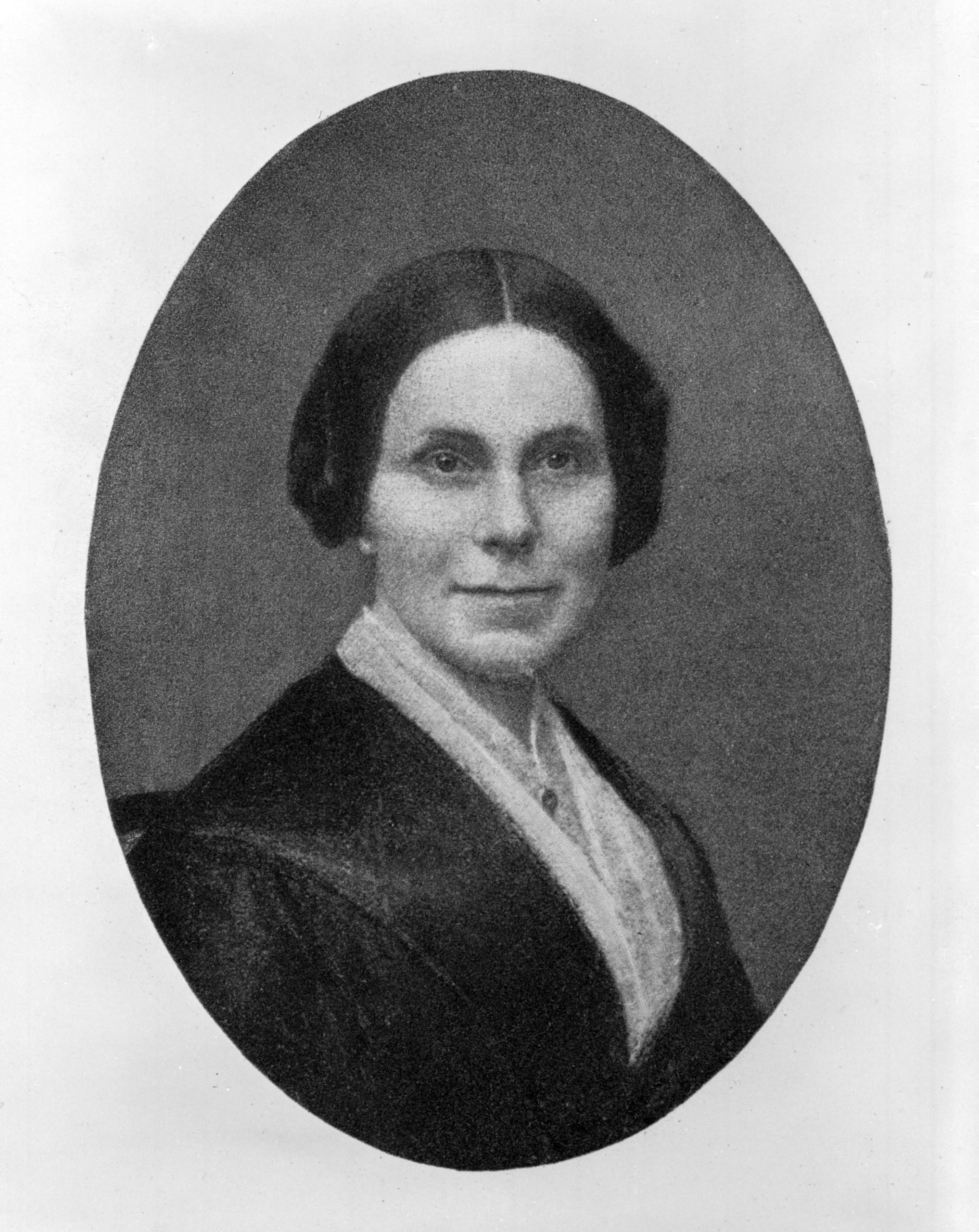

Elizabeth Buffum Chace and the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island

Essay by Elizabeth C. Stevens. Editor, Newport History

“My master had power and law on his side; I had a determined will. There is might in each.”

–Harriet A. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave-Girl, Written by Herself.1Harriet A. Jacobs Incidents in the Life of a Slave-Girl, Written by Herself (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987). 85

“No guests were ever more welcome to my door, than those who came in the darkness of night, to escape from the human bloodhounds who were seeking for prey.”

–Elizabeth Buffum Chace2Letter from Elizabeth Buffum Chace, April 18, 1893, Old Anti-Slavery Days. Proceedings of the Commemorative Meeting Held by the Danvers Historical Society, at the Town Hall, Danvers, April 26, 1893 [Danvers, Mass.: Danvers Mirror Print, 1893], 70-71

The Underground Railroad was neither underground nor a railroad

In the years leading up to the Civil War, enslaved people resisted their captivity by attempting to escape from bondage. By the 1830s, slavery had been outlawed in Rhode Island and other northern states, and most enslaved people in the North had been emancipated. Still, the economy of the United States was dependent on the labor provided by millions of men, women, and children enslaved in southern states. Enslaved people were considered valuable “property,” and their enslavers sought to retrieve them even after they had fled to the North by offering substantial rewards and engaging “slave catchers” to find and arrest them and return them into bondage. Therefore, the risks to escapees were very high. Those taken back into captivity were often brutally punished and even murdered to deter other enslaved persons from fleeing. Unitarian minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an abolitionist in Worcester, Massachusetts assisted freedom seekers, cited the bravery and courage of the men and women who escaped from the brutal conditions of slavery as on a par with any heroism that the world had ever known.3Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Out-door Papers (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1863), 42

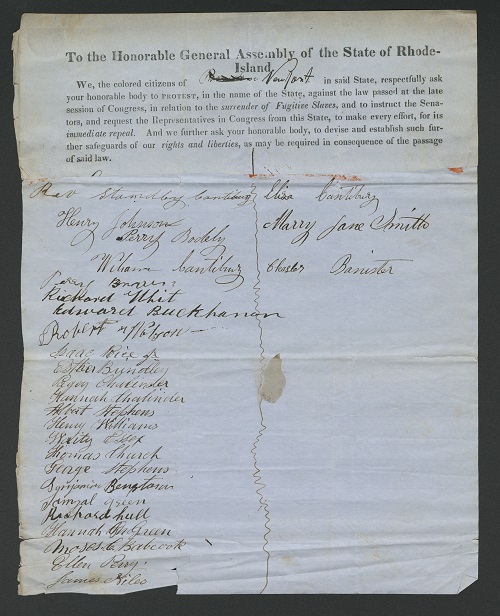

Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law from the “colored citizens” of Newport

Read more about Rhode Islanders' involvement in the Underground Railroad here

The “Underground Railroad” was the term used for thousands of sympathizers in both the North and South who assisted freedom seekers, especially in the North and even in Canada. The Underground Railroad was neither underground nor a railroad. It was an informal network of people who secretly aided freedom seekers by providing food, clothing, shelter, money, transportation, and information as enslaved people fled to freedom. Work for the Underground Railroad was clandestine and, therefore, “underground.” In Rhode Island and elsewhere, both Black and white people were engaged in the effort to shelter and protect enslaved people who had self-emancipated themselves. In the South, friends, relatives, and strangers help enslaved people to flee and during their perilous journeys. In writing of the Underground Railroad, historian Eric Foner has observed that, “Most escapes could not have been successful without the support of black communities, free and slave, north and south.” Foner asserts that “The networks assisting fugitives offered a rare instance in antebellum America of interracial cooperation.”4Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015), 18.19 Those who took part in any facet of the Underground Railroad enabled families and individuals to evade capture and re-enslavement.5William Still, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters &c., Narrating the Hardships Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in their Efforts for Freedom (pub. 1871, reprinted 1970, Chicago, Johnson Publishing Co.); Fergus M. Bordewich, The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: HarperCollins, 2005); Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1961)

The work of those who participated in the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island was shrouded in secrecy so that the freedom seekers they sought to protect could safely reach their destinations, and those who helped them could avoid jail or fines. Even after enslaved people in the South had been emancipated in 1863, people in Rhode Island who took part in the effort left little evidence of their work. Little is known about those who worked on the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island. One white Rhode Islander—Elizabeth Buffum Chace—left a brief first-person account of her activities that aided the flight of enslaved people to freedom.

Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Nineteenth-Century Mother and Antislavery Worker

Elizabeth Buffum Chace (1806-1899) lived a full, active, and long life. She was an antislavery activist before the Civil War and a woman’s rights advocate in the decades after it. She was a founder and president of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association, working to secure voting rights for women from 1868 until her death in 1899. Chace’s work in the antislavery movement before was the foundational experience of her life of activism, as recounted in her slim volume, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences.6Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E.L. Freeman, 1891 Chace’s account was re-published in 1937 under the title “My Anti-Slavery Reminiscences,” and included in a book about Chace and her sister Lucy Buffum Lovell. The re-print was edited by a descendant of Lucy Lovell, with material deleted and added from other sources that Chace did not use in her original volume.7Malcolm Lovell, ed., Two Quaker Sisters [New York: Liveright Publishing Co., 1927], 110-182)

Elizabeth Buffum Chace was a twenty-six-year-old mother when she became a convert to the cause of radical anti-slavery activism. She was a birthright Quaker, born in Rhode Island and raised partially by her grandparents in a Quaker enclave in Smithfield. Elizabeth Buffum had moved to Fall River in the mid-1820s. In 1828, she married Quaker textile manufacturer Samuel B. Chace and began to raise her family there. Quakers were opposed to slavery, but many did not accept antislavery activism among their members. Arnold Buffum, Chace’s father, was the first president of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, which advocated for the immediate abolition of slavery. Many in the North accepted slavery as a given, and among those few who publicly opposed it, some argued that it would be too disruptive to end the practice of slavery all at once. A small fraction of abolitionists like Arnold Buffum and his daughters, who favored the immediate elimination of slavery, were considered by most Americans to be dangerous agitators willing to risk tearing apart the union of the United States. When he was a child, Arnold Buffum’s family in Smithfield had sheltered and protected freedom seekers who had fled enslavement in New York State.8Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 8-12

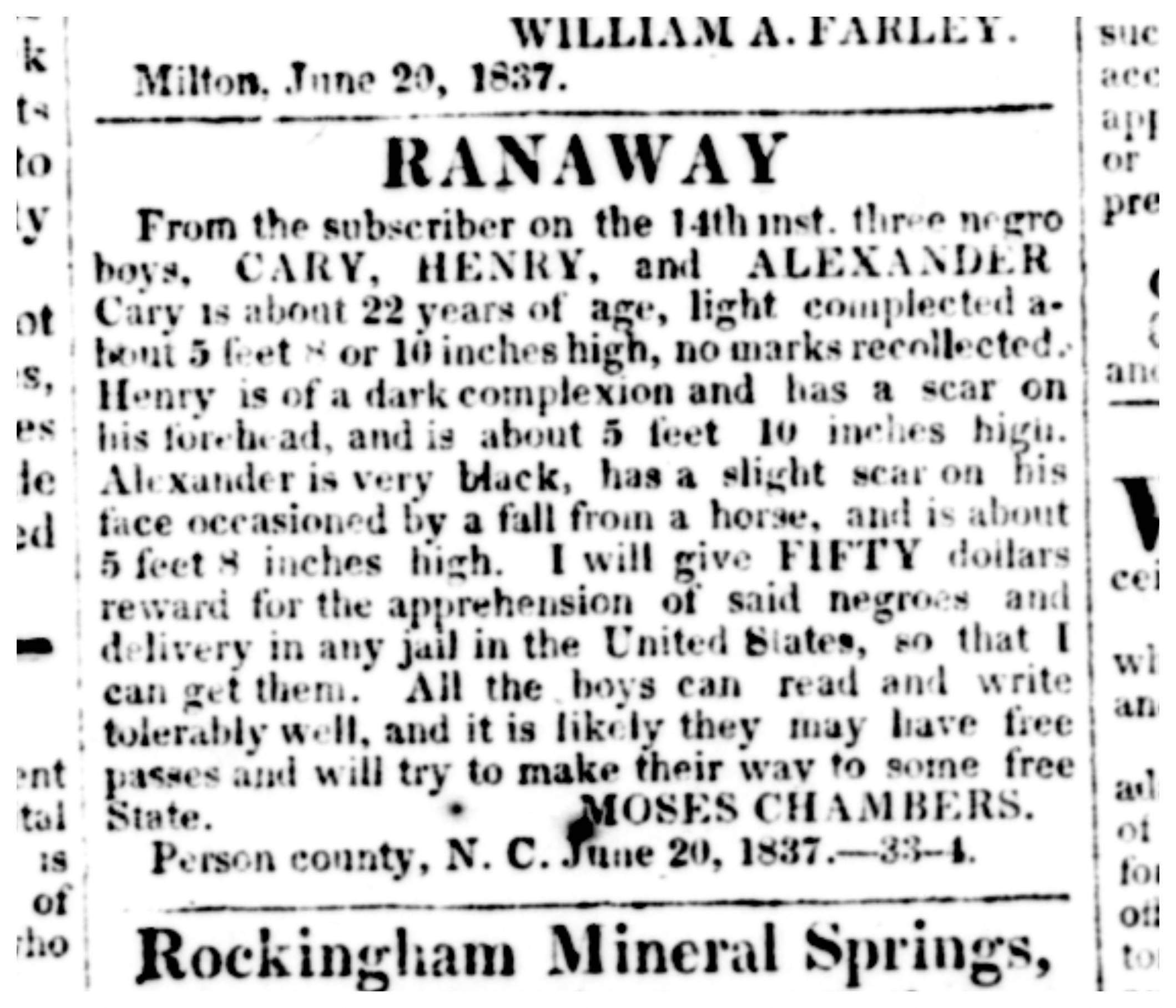

Runaway Advertisement for James Curry

Read about James Curry here

In the 1830s, with her sisters and other women, Elizabeth Buffum Chace formed the Fall River Female Antislavery Society, which brought antislavery lecturers to Fall River. The women organized fairs to raise money for the cause and carried petitions throughout the town to be signed by Fall River residents and sent to Congress.9Elizabeth C. Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman: A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist and Workers’ Rights Activism (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003), 22-29 Although some women in the Fall River Female Anti-Slavery Society objected, Chace and her sisters successfully argued that African-American women should be admitted as members. Sometime around 1838, Chace became involved in the clandestine work of the Underground Railroad in Fall River. We know that around this time, she and her husband sheltered James Curry, a formerly enslaved man, after he fled a brutal enslaver in North Carolina. Chace continued to maintain contact with Curry after he safely arrived in Canada.10Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 12-14, 16-17; [Elizabeth Buffum Chace], “The Narrative of James Curry,” The Liberator, January 10, 1840

Chace’s life at this time was beset by tragedy when all five of her young children died of various illnesses between 1837 and 1843.11Her two-year-old daughter, Susan, died after a short illness in 1837. In 1839, her oldest child, George, died at the age of 9 after a lingering illness, and six months later, her daughter Adelia, 7, died of scarlet fever. Her son, John Gould Chace, died of scarlet fever when he was six years old in 1842, and the baby, Oliver, died at 18 months, during the next year (1843) when Chace was pregnant with her sixth child After the death of her youngest child, Elizabeth Buffum Chace took the momentous step of leaving the Quaker meeting because it was not hospitable to radical antislavery activity among its members. She eventually had five more children, the youngest of whom was born in 1852 when she was forty-five years old. The deaths of her children and her work as a mother only strengthened her resolve to work for an end to slavery. She felt a kinship with enslaved mothers who were cruelly separated from their own children and vowed to dedicate her life to fighting for their freedom.12Undated manuscript, December 13, 1842, Elizabeth Buffum Chace Family Papers, Ms 89.12, Brown University; Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 30-42

“To escape the vigilance of the mercenary human blood hounds”: The Underground Railroad in Valley Falls, R.I.

In 1839, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Samuel Chace left Fall River and, after living in temporary housing in Pawtucket, moved to Valley Falls, Rhode Island, in 1840. Valley Falls was a town that straddled the Blackstone River in what is now southern Cumberland and Lincoln. There, Samuel Chace managed a textile mill, the Valley Falls Company, owned by his father.13Robert Grieve, An Illustrated History of Pawtucket, Central Falls and Vicinity (Pawtucket: Pawtucket Gazette and Chronicle, 1897), 170 The Chaces built a house on the Cumberland side of the Blackstone River in Valley Falls. In 1857, the family moved to a larger stone house known as “The Homestead,” on the Smithfield side of the Blackstone River (now Lincoln), also in Valley Falls.14Lillie Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 71, 134-35 In Valley Falls, Elizabeth Buffum Chace continued her antislavery work by organizing meetings and speakers. She provided lodging at her homes in Valley Falls for such notable antislavery advocates as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Sojourner Truth, Abby Kelley Foster, Charles Lenox Remond, and Lucy Stone.15Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 50

In both the Cumberland house and the Homestead, the Chace family aided and sheltered the formerly enslaved, seeking to “escape the vigilance of the mercenary human blood hounds,” as she referred to the slave hunters who searched for people who had escaped slavery. Elizabeth Buffum Chace explained in her memoir that some of the people she aided had been enslaved in Virginia and fled bondage by taking passage “either secretly or with consent of the Captains” via “small trading vessels” at Norfolk or Portsmouth. They were assisted by Black mariners who served on the ships involved in the trade between northern and southern ports and other enslaved and free Black people who worked on and around the docks in the southern coastal towns and cities. Some of these stowaways ended up in New Bedford, a prosperous coastal town in Massachusetts that was hospitable to enslaved people seeking freedom.16Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27; Kathryn Glover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 78, 157-260

Chace and others worked out a route with several segments to aid freedom seekers fleeing via southeastern Massachusetts. New Bedford residents would arrange for them to travel to Fall River. There, the formerly enslaved people were sheltered by antislavery sympathizers, including Nathaniel B. Borden, a prosperous merchant and politician, and his wife, Chace’s older sister, Sarah Buffum Borden.17Arthur Sherman Phillips, Phillips History of Fall River, Fasicle III (Fall River: Dover Press, 1946), 132-133 Then, “In the darkness of night,” Fall River resident Robert Adams drove the escaped individuals or families in a “closed carriage” to the Chace home at Valley Falls. Adams, a bookstore owner, was obliged to travel by night and with the carriage curtains drawn lest the presence of freedom seekers be detected.18Edward Stowe Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River and the Operation of the Underground Railroad (Fall River: Fall River Historical Society Press, 2017), 17-26; “Robert Adams,” in Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2008), 1:13; Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 38 There was a special sense of urgency if slave hunters were known to be in the vicinity looking for particular “runaways,” as their capture would mean re-enslavement, perhaps vicious punishment, and even death.

The Chace family welcomed refugees from slavery into their home in Valley Falls. Like many northerners who were abolitionists but who also shared some prevalent racist notions about Blacks, Chace at first believed that enslaved people had suffered mental decline caused by their traumatic experiences. However, she and her family, “were surprised at the amount of intelligence and sharp-sightedness displayed by these victims of cruelty.”19Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 38 The formerly enslaved people stayed only briefly. When it was deemed safe, Samuel Chace assisted the freedom seekers onto a car on the Providence and Worcester railroad, asking a sympathetic conductor to watch out for them. Continuing on their grueling quest for freedom, the people who had sheltered with the Chaces were transferred at Worcester to a train heading to Vermont. When they arrived in Burlington, Vermont, the freedom seekers were met by Joshua Young, a Unitarian minister who guided them on the final leg of their journey from Burlington to Canada.20Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27-28; Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River, 87-93; “Joshua Young” in Snodgrass, Encyclopedia, 2:592 Elizabeth Buffum Chace gave the escaped people an empty envelope addressed to the Chaces in Valley Falls, to be mailed when they reached Canada. When the envelope reached Valley Falls, she then knew “by its post-mark,” that the persons had arrived safely.21Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 28 Having to make a number of stops while evading re-capture made the long journey especially dangerous and harrowing for the freedom seekers. Every time they paused on their way, they risked being discovered by people who lived in the vicinity. Having to linger in a house, waiting for assistance to go the next leg of the journey, exposed the freedom seekers to possibly being found out.

“Still fearing their capture on the road”:The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increases the danger

The Fugitive Slave Act was passed by Congress in 1850. It made it explicitly illegal for anyone living in the North to thwart the work of slave catchers and required northern residents to aid in the pursuit of the self-emancipated. Under the terms of the law, even persons who had fled slavery decades earlier, who had established families, employment, and roots in their northern U.S. communities, could be re-captured and returned to slavery. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, some of those individuals and families who had previously settled in the North decided to flee to Canada from northern locales via the Underground Railroad. Black and white abolitionists and residents of New England who aided them, such as Elizabeth Buffum Chace, were liable to fines and imprisonment for sheltering and aiding those who had escaped enslavement. Many white northerners maintained that although they did not like slavery, they were bound to obey the law and to assist those searching for freedom seekers in northern states.

Although their names are not given in her narratives, Chace related several accounts of freedom seekers who stayed at her home in Valley Falls. She told of a man who had fled from Portsmouth, Virginia, to New Bedford with his family and found work. He was a skilled worker, (perhaps a blacksmith) and therefore “valuable property.” About a year later, his whereabouts were discovered by his former enslaver, who went to New Bedford seeking to take him back to slavery. Some African Americans in New Bedford quickly alerted abolitionists, and the man was spirited away to Fall River. Because his re-capture was possibly imminent, Quaker sympathizers there did not dare to wait until nightfall to send him to Rhode Island. When he arrived in Valley Falls, “the large noble-looking colored man” was dressed in a Quaker bonnet and shawl. He apparently found his disguise quite amusing when he arrived at the Chace home in Valley Falls. Chace noted that the hunted man carried “a revolver in his pocket and vowed that, had he been overtaken on the road, he would defend himself to the death. . .for no slave would he ever be again.” He spent the night in Valley Falls, and Elizabeth Buffum Chace wrote, “We sent him off on the early morning train, with fear and trembling; but had the happiness in a few days to learn of his safe arrival [in Canada]. . . and that afterwards, he had been joined by his wife and child.”22Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27-28; Lillie B. Chace Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” Atlantic 64 (August 1889), 168

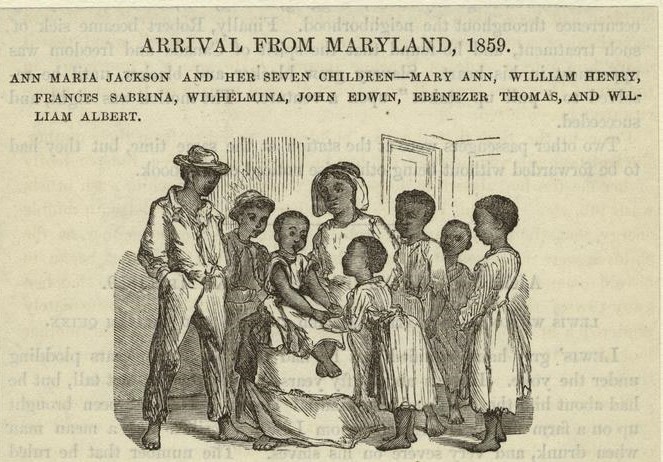

Engraving of Ann Maria Jackson and her Seven Children

Learn how children and teens participated in the Underground Railroad here

Another account that Elizabeth Buffum Chace related in her Reminiscences demonstrates that the Underground Railroad was a truly cooperative effort in which dozens of individuals, Black and white, might be involved to rescue even one person. Chace told of two men in their twenties who had stowed away on a trading vessel out of Portsmouth, Virginia, headed for Wareham, in southeastern Massachusetts. They were hidden and protected during the voyage “through the friendly interest of the colored steward.” On landing in Massachusetts, one of them was discovered in his hiding place aboard the ship, but managed to evade the captain’s efforts at recapture. Although the captain ordered sailors to “stop him,” the sailors apparently abetted his escape because they “never stirred.” The man was then aided in his flight by an African-American woman, her son, and their neighbors in the town, who took him in and fed and clothed him. He told them about the other freedom seeker aboard the ship, and they requested help from a sympathetic white resident, who then rescued another man from his hiding place aboard the ship. Alerted by members of the African-American community, New Bedford abolitionists arranged for transportation for both young men to Fall River. From there, Robert Adams drove them to Valley Falls in his carriage. The two men were not dressed warmly enough for a February journey to Canada. But, with the “help of one of our neighbors,” the men were given “warmer clothing for their winter journey northward…” They arrived safely in Canada after consecutive encounters with dozens of sympathetic people.23Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 30-33; Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” 169

Chace wrote of a formerly enslaved woman who had settled in Fall River prior to the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law and who felt compelled to flee once it was passed. One night, “good Robert Adams aroused us with a carriage full—a woman and three children.” The mother had escaped from Maryland with her family “some time before” and had established herself at Fall River “as a laundress” and “was doing well.” When she learned that a notorious slave catcher had been “seen prowling around the neighborhood where colored people lived, and. . . suspiciously, peering into the stable” where her [teen-aged] son had previously been employed, the mother was alarmed. Chace’s Fall River contacts swiftly brought the woman and her three younger children to wait at Valley Falls for her eldest son to arrive from a farm in the vicinity of Fall River where he worked.

Chace’s account reveals the almost unbearable tension that these formerly enslaved people endured even while exhibiting unremitting courage on their flight. The family stayed for several days, ‘in hourly fear and expectation of the arrival of the slave-catcher.” The Chaces’ “doors and windows [were] fastened by day as well as by night,” and she did not “dare to let our neighbors know who were our guests, lest some one should betray them.” Chace remembered that her “faithful Irish servants declared that they would fight, before the woman and her children should be carried into slavery.” Chace undoubtedly inadvertently added to the mother’s sense of danger by telling her that if the family were apprehended on the northbound train, the woman should attempt to give her youngest child, a two-year-old girl, who “looked nearly white,” to “some kind looking person,” to be sent back to the Chaces. Finally, the son arrived, “and we sent them off,” Chace remembered, “still fearing their capture on the road.” Samuel Chace accompanied the hurried family part-way on the train to Worcester. He handed care of them over to the conductor who assured him that the family would be looked after, “and if no train was going North soon enough to secure their safety,” the railway superintendent had promised to “put on an extra train” to speed them on their way. Chace concluded, “The envelope came back with the Toronto post-mark, and the man-stealers lost their prey.”24Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 34-38

“No guests were ever more welcome to my door”: Elizabeth Buffum Chace and the Underground Railroad

Her experiences in the antislavery movement aiding formerly enslaved people to escape to freedom were formative for Elizabeth Buffum Chace. She believed that the most noble work that young people can do in life is to labor for a “great cause.” She encouraged the readers of her little book, Antislavery Reminiscences, to be inspired by the work of antislavery activists and by the heroism of those enslaved people who chose a dangerous path to freedom. Writing her memoir in 1891, Chace, who by then had spent almost twenty-five years working for woman suffrage in Rhode Island, observed that although her readers could no longer be abolitionists, they could adopt another “great cause”—that of woman suffrage.25Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 46-47 Nevertheless, her activist impulses were rooted in the radical abolition movement and her participation in the vast web of helpers that was the Underground Railroad had a special place in her life story of activism. Perhaps she shared some of the sentiment of her antislavery and woman suffrage 26For more information on the struggle for woman suffrage in Rhode Island please see our Encompass chapter[link]colleague and friend, Frederick Douglass, who wrote of helping men, women and children escape from bondage: “I can say I never did more congenial, attractive, fascinating and satisfactory work. . . . it brought to my heart unspeakable joy.”27Frederick, Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications Inc., 2003), 190

Terms:

Freedom Seekers: freedom seekers are enslaved individuals who liberated themselves from enslavement. You may see the term “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” used in older documents or texts. Recent scholarship acknowledges that “freedom seekers” or “self-emancipated” are preferable to use since the other terms places the individual in a lawbreaking context, or one deserving of capture and punishment. See the National Park Service’s “Language of Slavery” for more information

Clandestine: secret or hidden

Self-Emancipated: individuals who have liberated themselves from enslavement. You may see the term “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” used in older documents or texts. Recent scholarship acknowledges that “freedom seekers” or “self-emancipated” are more accurate terms to use since the other terms places the individual in a lawbreaking context, or one deserving of capture and punishment. See the National Park Service’s “Language of Slavery” for more information

Fugitives: people fleeing from slavery. In the narrative, we prefer to use the term “freedom seeker.” However, you may see the term “fugitive” in other works, within our narrative if it is part of a quotation, or when part of the name of the Fugitive Slave Law.

Antebellum America: America in the decades before the Civil War

Emancipated: freed

Antislavery activists: people who worked to end slavery in the United States

Quaker: a member of the Society of Friends, a religious group that had banned the practice of slavery among its members. Quakers also advocated for many other causes, including women’s suffrage, prison reform, and pacifism.

Abolitionists: people who worked for the elimination of slavery in the U.S.

Enslaver: someone who enslaved people and benefited from their labor

Slave hunter: a person who tracked down formerly enslaved people in order to capture them and return them into slavery.

Mariners: men who worked aboard ships.

Stowaways: people hidden on board a boat or ship

Runaways: a term used for people who escaped from enslavement

Refugees: people who leave their homes to flee from a dangerous or life-threatening situation

narratives, stories or accounts

Narrative: story

Colored: in the nineteenth century, it was common usage to refer to a Black person as “colored”

Inadvertently: not on purpose

Questions:

Why do we know so little about the Underground Railroad? What is the Underground Railroad?

Why is the term “freedom seeker” used? Why do some scholars believe terms like “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” are no longer appropriate? Do you agree? Why or why not?

What does “self-emancipated” mean? What does it mean to have agency, and in what ways did enslaved people express agency?

- 1Harriet A. Jacobs Incidents in the Life of a Slave-Girl, Written by Herself (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987). 85

- 2Letter from Elizabeth Buffum Chace, April 18, 1893, Old Anti-Slavery Days. Proceedings of the Commemorative Meeting Held by the Danvers Historical Society, at the Town Hall, Danvers, April 26, 1893 [Danvers, Mass.: Danvers Mirror Print, 1893], 70-71

- 3Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Out-door Papers (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1863), 42

- 4Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015), 18.19

- 5William Still, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters &c., Narrating the Hardships Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in their Efforts for Freedom (pub. 1871, reprinted 1970, Chicago, Johnson Publishing Co.); Fergus M. Bordewich, The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: HarperCollins, 2005); Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1961)

- 6Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E.L. Freeman, 1891

- 7Malcolm Lovell, ed., Two Quaker Sisters [New York: Liveright Publishing Co., 1927], 110-182)

- 8Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 8-12

- 9Elizabeth C. Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman: A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist and Workers’ Rights Activism (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003), 22-29

- 10Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 12-14, 16-17; [Elizabeth Buffum Chace], “The Narrative of James Curry,” The Liberator, January 10, 1840

- 11Her two-year-old daughter, Susan, died after a short illness in 1837. In 1839, her oldest child, George, died at the age of 9 after a lingering illness, and six months later, her daughter Adelia, 7, died of scarlet fever. Her son, John Gould Chace, died of scarlet fever when he was six years old in 1842, and the baby, Oliver, died at 18 months, during the next year (1843) when Chace was pregnant with her sixth child

- 12Undated manuscript, December 13, 1842, Elizabeth Buffum Chace Family Papers, Ms 89.12, Brown University; Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 30-42

- 13Robert Grieve, An Illustrated History of Pawtucket, Central Falls and Vicinity (Pawtucket: Pawtucket Gazette and Chronicle, 1897), 170

- 14Lillie Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 71, 134-35

- 15Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 50

- 16Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27; Kathryn Glover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 78, 157-260

- 17Arthur Sherman Phillips, Phillips History of Fall River, Fasicle III (Fall River: Dover Press, 1946), 132-133

- 18Edward Stowe Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River and the Operation of the Underground Railroad (Fall River: Fall River Historical Society Press, 2017), 17-26; “Robert Adams,” in Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2008), 1:13; Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 38

- 19Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 38

- 20Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27-28; Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River, 87-93; “Joshua Young” in Snodgrass, Encyclopedia, 2:592

- 21Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 28

- 22Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 27-28; Lillie B. Chace Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” Atlantic 64 (August 1889), 168

- 23Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 30-33; Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” 169

- 24Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 34-38

- 25Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 46-47

- 26For more information on the struggle for woman suffrage in Rhode Island please see our Encompass chapter[link]

- 27Frederick, Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications Inc., 2003), 190