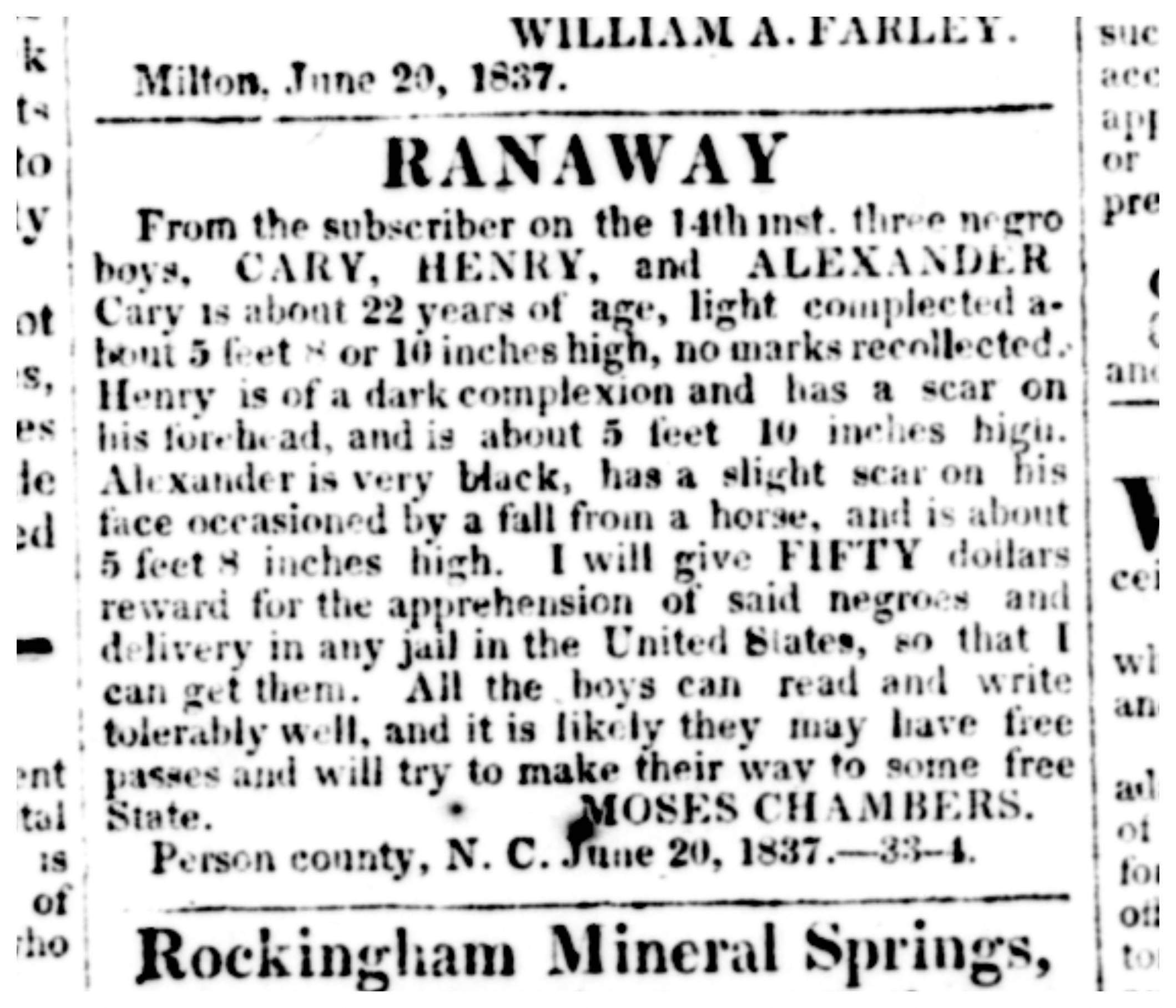

Runaway Advertisement for James Curry

This “runaway” advertisement appeared in the July 11, 1837 edition of a newspaper called Milton Spectator out of Milton, North Carolina. The advertisement lists James Curry (as “Cary”) and his brothers. The advertisement was placed by his enslaver, Moses Chambers. This following essay tells the story of James Curry’s life as an enslaved man and his self-emancipation to freedom.

The electronic scan of the advertisement can be found on the University of North Carolina’s digital archives page.

The Narrative of James Curry

Essay by Elizabeth C. Stevens. Editor, Newport History

In the decades before the Civil War, a number of formerly enslaved people wrote and published slave narratives. A “slave narrative,” also now called a “freedom” or “liberation” narrative, was an account of a person’s captivity and escape from bondage. Antislavery activists sometimes assisted formerly enslaved people in writing or shaping their stories. Those who worked for the abolition of slavery felt that publicizing these dramatic first-person accounts of enslaved life would convert others to support the antislavery cause. Abolitionists knew that there was tremendous power in the words of formerly enslaved people describing their lives in bondage and their difficult quest for freedom.1“North American Slave Narratives,” introduction by William L. Andrews, accessed March 2, 2011 [link]; Frances Smith Foster, Witnessing Slavery: The Development of the Ante-Bellum Slave Narratives (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994

Rhode Islander Elizabeth Buffum Chace, an antislavery activist, joined the radical abolitionist movement in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the 1830s. While living in Fall River, she and her husband and other activists assisted a young man, James Curry, who had fled from slavery in North Carolina. It appears that James discarded his slave name, which had been “Cary,” and adopted a new one when he arrived in the North.2See footnote about Cary’s “Runaway” Advertisement below. According to Chace’s Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, Curry’s arrival in Fall River and the months he spent there in 1837 and 1838 galvanized the abolitionists’ efforts to assist other freedom seekers.3Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E. L. Freeman, 1891), 27 While he was staying in Fall River, possibly at her house, Chace had written down the details of Curry’s life and turned them into a “narrative.” It is likely that Curry told his story to Chace, with the expectation that it would be published or otherwise shared with the public as part of abolitionists’ efforts to bring an end to slavery.

After moving back to Rhode Island in 1839, Chace sought to publish Curry’s story. The “Narrative of James Curry, A Fugitive Slave” was finished on September 30, 1838, but it did not appear in print until January 1840 in the Liberator, a fiery antislavery newspaper edited by William Lloyd Garrison in Boston. James Curry’s “narrative” filled almost the entire first page of the paper and finished on the second page. Two footnotes were added to the text in the Liberator. Both were styled as questions about the content of the Narrative (asked by a listener, perhaps Chace) and answered by Curry.4“Narrative of James Curry, A Fugitive Slave,” Liberator, January 10, 1840; on William Lloyd Garrison, see Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000)

It is not clear whether James Curry dictated his account to Elizabeth Buffum Chace or whether she made notes while listening to him speak and afterward re-worked his story in her own words. Years later, Chace’s daughter maintained that Elizabeth Buffum Chace had written out [Curry’s] narrative “in autobiographical form as taken from his lips.”5Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Her Environment (Boston, W.B. Clarke, 1914), 71 A re-publication of the “Narrative of James Curry” included a note, possibly from Chace, that she replicated the “story as he told it many times to me. . .”6Malcolm Lovell, ed., Two Quaker Sisters (New York: Liveright, 1937), 136 In any event, Chace composed Curry’s narrative in the first person, as though he himself were speaking.

“We commenced work as soon as we could see in the morning”: James Curry’s childhood

James Curry’s account begins, “I was born in Person County, North Carolina.7Person County is located in the north-central part of the state, along the border of Virginia My master’s name was Moses Chambers.”8Moses Chambers genealogical profile [link] Curry was born about 1815.9Moses Chambers’ “Runaway” advertisement published in July 1837, listed Curry (or “Cary”) as “about 22 years of age.” N. C. Runaway Slave Advertisements, Accessed March 2, 2021 [link]

Curry first recounted the history of his mother, Lucy, “the daughter of a white man and a slave woman.”10Curry never named his mother in the Narrative. However, a relative of his enslaver identifies James as “one of Lucy’s boys” As a young woman, Lucy made two unsuccessful attempts to flee captivity, but stopped trying to escape after she had children. Curry’s father, Peter Burnet, was a “free colored man.” When James Curry was young, his father moved with an employer to a different part of the South, and the family never saw him again.11In a “summary” of James Curry’s “Narrative,” Erin Bartels Butler writes that James Curry’s father was “sold into slavery” after leaving North Carolina. Accessed March 10, 2021 [link] Curry remembered his mother as a “proud-spirited woman” who insisted that her children have two names—not the single name usually given to babies born in slavery. Curry related that his mother was “a very good and tender mother.”

During his childhood, James Curry worked as a “domestic servant.” Although literacy among enslaved people was outlawed, he persuaded the son of Moses Chambers, a boy who was about his age, to secretly teach him to read and write. Curry learned to read and write and often surreptitiously read a Bible in the house where he worked.

Curry recalled that Moses Chambers’s wife treated him in a “kindly” manner but was “very cruel” to other enslaved persons, even children. As a boy, he witnessed a savage attack on a young girl who was nine or ten years old. Chambers’ wife beat the girl’s naked body repeatedly with “willow twigs” and when her arm was tired, the woman would “thrash the girl on the floor and stamp on her with her foot, and choke her to stop her screams.” The beating continued for some three hours. The girl eventually died of injuries sustained that day.

Curry described the intense labor and ill-treatment of the enslaved people where he lived. When he turned sixteen, Curry began daily work in the fields. “We commenced work as soon as we could see in the morning,” growing and harvesting tobacco, grain, and cotton. The enslaved workers labored until noontime before they were permitted to have breakfast, and “then until dark, when we had our dinner, and hastened to our night-work for ourselves.” They were allowed just two meals per day. Breakfast, at noontime, was “warm cornbread and buttermilk.” Dinner, between eight and nine o’clock in the evening, consisted of “cornbread, or potatoes and the meat which remained from the master’s dinner or one herring apiece.”

After a full day of toil, enslaved people would work for themselves “in the night upon their little patches of ground, which they had cleared, raising tobacco and food for hogs.” They were allowed to barter or sell items to obtain clothing and food and eat any produce they grew. After they had cleared and successfully cultivated these small “patches” of land, their enslaver, Chambers, would expropriate their developed land for his own use, and the enslaved workers would be forced to begin again on another barren plot of earth.

“I must stand there”: The assault on Lucy Curry

James Curry’s mother was in charge of many domestic chores in the house, and he described her “labor” as “very hard.” She rose early to milk fourteen cows and then was burdened with preparing meals to feed both her enslaver’s family and the enslaved people who lived there. She cooked every day for some thirty or more people, provided child care for enslaved families and her enslaver’s family of seven children, and did the household’s laundry and ironing. Curry estimated that his mother had “the care of from ten to fifteen children whose mothers worked in the field.” After her chores were done, late in the evening, as she alternately dozed and worked in her own quarters, Lucy sewed and mended clothes for her family and others whom she cared for, including three enslaved orphans whose mother had died.

One of James’s traumatic memories of his childhood was when Chambers’ daughter assaulted his mother, who pushed the young woman away. For having defended herself, James’s mother was savagely beaten with a “hickory rod” by both the enslaver and his daughter. James witnessed this assault and remembered his trauma, “I must stand there, and did not dare to crook my finger in her defense.”

Curry worked in the fields during the spring and summer. In the fall and winter, he worked alongside his uncle in a “hatter’s shop.” His mother’s brother was a skilled artisan and contributed to their enslaver’s income by making and selling hats.

“Just to let them know he was their master”

Curry recalled Judge “Cammon” [Cameron] from Raleigh, who owned a plantation in the neighborhood.12Judge Duncan Cameron (1777-1853) was a lawyer, judge, banker and legislator. His family was among the largest landholders in North Carolina and owned plantations in Alabama and Mississippi as well. 13Sydney Nathans, To Free A Family, The Journey of Mary Walker (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012); accessed March 1, 2021 When traveling about the area, the judge wielded a “large cane.” If he met a Black person “on the road,” Curry remembered, and the person did not show the judge what he considered to be proper deference, the judge “would beat him with his cane.” Judge Cameron “would whip enslaved people for no offense, just to let them know he was their master,” James Curry recalled.14On a website noting Cameron’s prominence as a large plantation owner, lawyer, legislator, and in North Carolina, it is noted that “Cameron’s legacy in Ohio is much different. A slave who escaped to Salem, Ohio, with the assistance of Quakers, told a story about Cameron, which is not known in NC [North Carolina] today. Apparently, when Cameron walked the streets of Raleigh or Hillsborough and saw a slave, he would hit the slave on the top of the head with the brass ball on his cane as a reminder of the status of blacks. This story has made it into the underground railroad annals in Ohio, but has not made it back to NC.” Accessed February 28, 2021 [link]

James Curry wrote that his enslaver, who also bought and sold enslaved people, “was not a cruel master only at times.” He noted that Chambers “was considered a good man among slave-holders. Yet, he was a narrow-minded, covetous, unfeeling man.” One time their enslaver gave Curry’s mother two “sickly” piglets. She fed and took care of them, but when they “got to be nice large hogs” the “master” took them back for his own family. Likewise, when James was given two little pigs by the local miller, he raised them on produce from his little garden patch. When these pigs were slaughtered, James and his mother were whipped for keeping some pieces of meat for themselves. Although James maintained that Chambers “seldom whipped his slaves cruelly,” there were times “when he began to whip a slave” and ‘it seemed as though he never knew when to stop. He usually was drunk as often as once a week, and then, if anything occurred to enrage him, there was no limit to his fury.”

As the narrative showed, violence upon enslaved people was omnipresent. James witnessed the punishment of two enslaved men, one accused of stealing and selling wheat and the other accused of buying the stolen wheat. The men were “stripped and tied each to a fallen tree.” Two enslavers, one of whom was the adult son of Chambers, Curry’s own enslaver, “commenced beating” the men at eight o’clock in the morning. They attacked the men “with willow sticks, from five to six feet in length, tied together in bunches of from three to five. . . [T]he two enslavers continued beating the men until one o’clock in the afternoon. . . Their passions seemed to rise and fall like the waves of the sea, and the poor creatures suffered accordingly,” Curry remembered. One of the men “was all the time shrieking, and begging, and pleading for mercy” to no effect.

Excessive physical chastisement was not the only form of torment that James described. “As soon as this unmerciful torture was completed,” Curry related, his enslaver’s son “went directly to the tavern, where he had a drove of slaves ready to start, and set off for Alabama.” The Narrative then digressed as Curry addressed his Northern readers. “I wish some of your people could see a drove of men, women, and children driven away to the south.” “Husbands and wives, parents and children torn from each other. Oh! the weeping, the most dreadful weeping and howling!” Curry informed all “who might read this narrative, that there is no sin which man can commit, that those slaveholders are not guilty of.”

“Freedom reigned predominant in my breast”: Curry’s plan to escape his bondage

Vicious beatings upon the bodies of enslaved people fed their desire to be free. Curry asserted, “From my childhood, the desire for freedom reigned predominant in my breast, and I resolved, if I was ever whipped after I became a man, I would no longer be a slave. . .[N]o slave would dare to say, in the presence of a white man, that he wished for freedom. But among themselves, it is their constant theme. No slave thinks they were made to be slaves. Let them be ever so ignorant, it is impossible to beat it into them that they were made to be slaves. I would look at the birds as they flew over my head or sung their free songs upon the trees and think it strange that, of all God’s creatures, the poor negro only was held in bondage.” James felt impelled to tell his story because he believed that people in the North must not yet know what slavery was; if they did, he believed, they would instantly act to eradicate it.

When he was twenty, Curry fell in love with “a free young woman of color.” He was forbidden to marry her by his enslaver, who “swore he would slit my throat from ear to ear” if Curry should marry a “free” woman. Due to his master’s refusal to sanction the marriage, Curry related, “We did not dare to have any even of the trifling ceremony allowed to the slaves, but God married us.” When his enslaver discovered that Curry had defied him, he threatened to separate him from his wife and further vowed that he would cut Curry’s throat with a penknife. Curry related, “I told him he might kill me if he chose, I had rather die than be separated from my wife.” It is not known if Curry ever saw his wife again.

Sometime after his marriage, James Curry was placed in a situation in which his enslaver claimed that James had disobeyed him. An overseer flogged Curry with “a hickory rod and struck me some thirty or forty strokes over my clothes.” During the beating, James remembered, “I firmly resolved that I would no longer be a slave. I would now escape or die in the attempt. They might shoot me down if they chose, but I would not live a slave.”

James Curry’s self-emancipation

In June 1837, while his enslaver was away, James and his two younger brothers fled on horseback. After bidding farewell to his distraught wife, they “started without money and without clothes. . . but with our hearts full of hope. We travelled by night and slept in the woods during the day.”15Moses Chambers, James Curry’s enslaver, published an advertisement entitled “Ranaway” in the Milton, N.C. Spectator of July 11, 1837. Dated June 20, 1837, Chambers’s notice offered a $50 reward for “three Negro boys, CARY, HENRY, and ALEXANDER” who had left his premises on June 14th. “Cary” was James Curry, described by Chambers as “about 22 years of age, light complected, about 5 feet 8 or 10 inches high, no marks recollected.” After giving a physical description of “Alexander” and “Henry,” Chambers offered the monetary reward “for the apprehension of said negroes and delivery in any jail in the United States, so that I can get them. All the boys can read and write tolerably well, and it is likely they may have free passes and will try to make their way to some free State.” N. C. Runaway Slave Advertisements, Accessed March 2, 2021 [link]

Throughout his entire flight to the North, James was aided by African Americans. “We suffered much from hunger,” Curry remembered. He and his brothers sometimes went two or three days without eating. They dared not ask for food, “except when we found a slave’s, or free colored person’s house remote from any other, and then we were never refused, if they had food to give.” At one point the famished men were discovered and were separated, leaving Curry without his horse and on his own. Although lost and disheartened and attacked by a “wild beast,” he continued on. He had been warned by “a colored man” to “beware of Dumfries,” a town some twenty-eight miles southwest of Washington, D.C. On the outskirts of town, Curry jumped on a horse he found in a field so that he could ride through Dumfries without causing suspicion. When through the town, he let the horse go and continued on foot.

When James arrived in Washington, he “made friends with a colored family, with whom I rested eight days.” After leaving the capital, he became lost but “soon entered a colored person’s house on the side of the canal, where they gave me breakfast and treated me very kindly. . .” He traveled on through Williamsport and Hagerstown in Maryland and, on July 19th, arrived in the “free state” of Pennsylvania “with a heart full of gratitude to God.” After doing some odd jobs at a house in Chambersburg, he was warned by an African-American domestic worker that he was not safe there. James hurriedly left and made his way toward Philadelphia, where Quakers assisted him.

Although he was very disappointed that he could not send for his wife, Curry related that his “Friends”16The capitalization suggests that Chace could be referring to the Quakers in the Philadelphia area advised him that the situation in Canada was unsettled and aided him in heading to Massachusetts. He proceeded via New York and arrived in Fall River, where the fledgling abolitionist community, including Elizabeth Buffum Chace and her husband, Samuel, extended “kindness to the poor fugitive.” Although he had “not here found that perfect freedom which I anticipated,” James related, “yet I have never for the moment regretted that I thus sought my liberty.” It appears that James Curry left Fall River for Canada sometime around the end of 1838. He arrived safely in Canada sometime later in 1839.17In Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s draft of a letter to James Curry, dated January 15, 1840, Chace wrote that Curry had left “more than one year ago.” Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1:70

“Where the arm of the oppressor could not reach thee”: James Curry’s arrival in Canada

In January 1840, Chace wrote to James Curry from her temporary home in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where she lived before moving to nearby Valley Falls. She and her husband had been “very anxious” about him until Curry’s letter to a Fall River abolitionist “informed us of thy safe arrival on British ground, where the arm of the oppressor could not reach thee.”18Curry’s letter informing them of his safe arrival in Canada was sent to Richard C. French, an abolitionist colleague from Fall River. (Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 70; Edward Stowe Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River, and the Operation of the Underground Railroad (Fall River, Mass.: Fall River Historical Society Press, 2017), 29 She wanted to know how he felt as a “free man, no longer a ‘chattel personal’?” She wondered if he had found employment for “thy free hands” and “above all, has thy wife reached thee?” She promised to send Curry a copy of the Liberator with his “Narrative” in it.19Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1:70-71. Wyman refers to the version of Chace’s January 1840 letter as a “draft” that was “unaddressed.” It is not known if it was ever sent. It appears that James Curry left Fall River on or after the date of the Narrative (September 20, 1838) and before February 1839, as Chace mentions that two of her children had died (“Death has twice entered our dwelling”) since Curry left. Nine-year-old George Chace died on February 25, 1839; his younger sister, Adelia, died of scarlet fever in August. Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1: 70-71; on her children’s deaths, see ibid, 43, and Elizabeth Buffum Chace journal and miscellaneous papers, Elizabeth Buffum Chace Family Papers, Ms, 89:12, Brown University

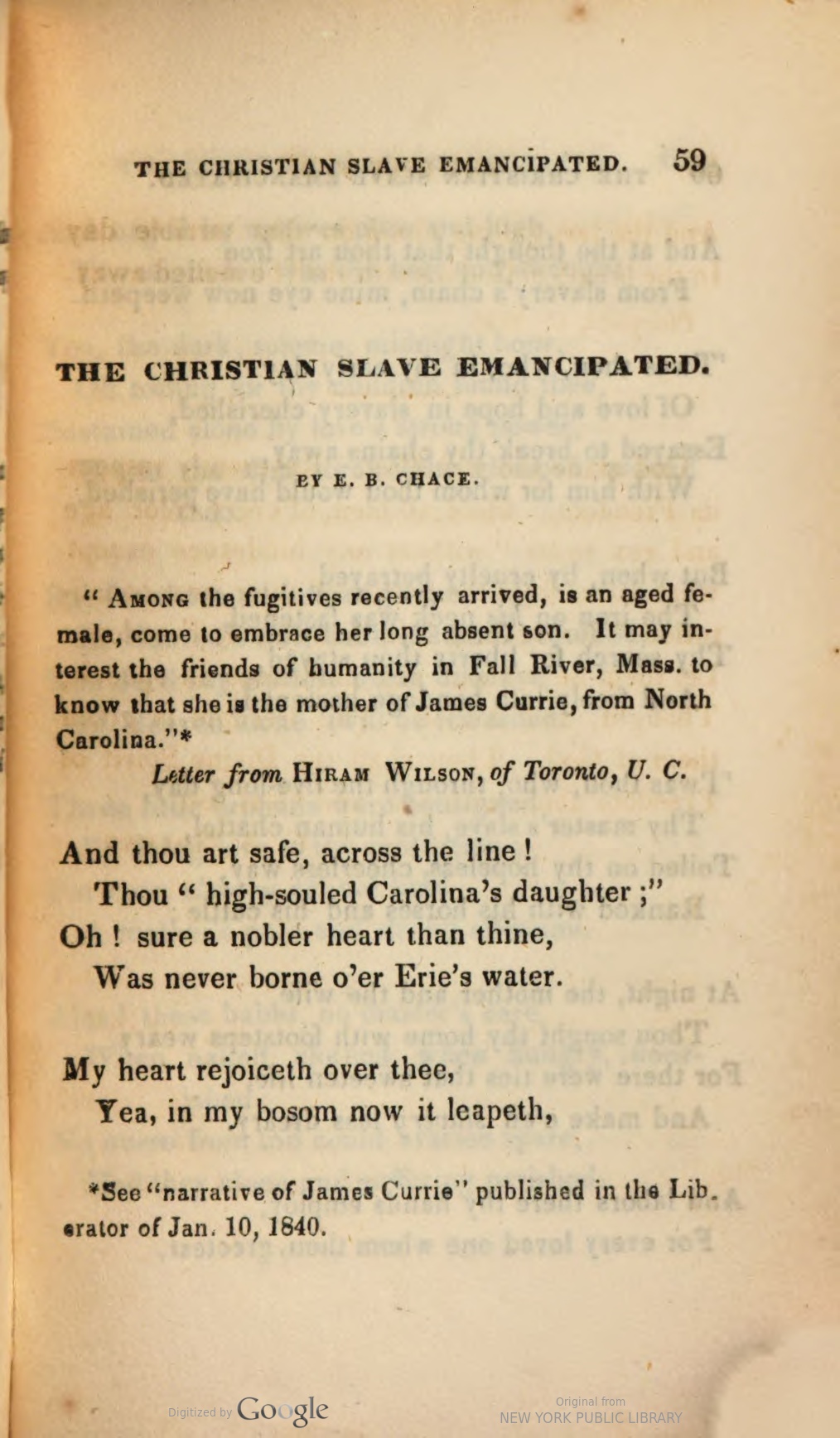

It is not known whether Elizabeth Buffum Chace or any abolitionists in Fall River who helped James Curry ever heard from him again after he informed them of his safe arrival in Canada. However, word somehow reached Chace that James Curry’s mother, Lucy, had managed to escape from bondage. She apparently arrived in Canada in 1840 and was reunited with her son. In response to the news, Chace wrote a 27-stanza poetic tribute to Curry’s mother, “The Christian Slave Emancipated.”

It was published by the Pawtucket Juvenile Emancipation Society, a children’s antislavery group in Pawtucket, in a small volume of poems and stories entitled, The Envoy From Free Hearts to the Free, which was sold to raise funds for the antislavery cause.20F. H. W. [Frances Harriet Whipple McDougall], ed., Pawtucket Juvenile Emancipation Society, The Envoy from Free Hearts to the Free (Pawtucket, R. I.: P. W. Potter, 1840)

“I am a free citizen of the United States”: Another assault in North Carolina

James Curry eventually moved from Canada to New York. In July 1865, just after the close of the Civil War, Curry traveled south to Person County, N.C., in search of family members whom he had not seen for thirty years. According to an account in an antislavery newspaper, Curry wanted to “find his family and remove them North.” He would have been over fifty years old. When Curry arrived in his home district, he was confronted by some white men who “roughly demanded” who his enslaver was. Curry responded, “I am a free citizen of the United States.” At this point, he was “collared, dragged from the house, beaten with violence over the head by a heavy stick,” which caused several wounds, and was “otherwise maltreated.” When he tried to run away, his assailants unsuccessfully attempted to shoot him. Curry went to Raleigh and reported the attack to Gen. Adelbert Ames, a Union military officer who was in charge of the district. Ames sent cavalrymen to arrest Curry’s assailants.21The National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 19, 1865 Almost immediately after the arrests, Gen. Thomas Ruger took over as the Union military commander in North Carolina. William Holden, who had been appointed provisional governor of the state protested to Ruger that prosecution in the attack on Curry could be handled by the civil courts and requested that the arrested men should be released from military confinement. Ruger responded that the military was compelled to intervene because attacks on, and even killings of, freedmen in North Carolina were taking place with no repercussions for the perpetrators by civil authorities. Gov. Holden claimed that Curry had “scarcely arrived in North Carolina and told his tale before he was apprehended under a warrant for an assault on one or more of the very persons of whom he complained.” Tension between military and civil authorities in the state was so acute that Holden eventually referred the matter of Ruger’s military jurisdiction to President Andrew Johnson.22William Holden to Thomas Ruger, July 27, 1865, Ruger to Holden, August 1, 1865, Horace Raper, ed., The Papers of William Woods Holden, 1841-1868, vol. 1 (North Carolina Department of Archives and History), 2000, accessed May 12, 2020 [link]; William W. Holden to Thomas Ruger, August 8, 1865, in Elizabeth Gregory McPherson, “Letters from North Carolina to Andrew Johnson (Continued),” The North Carolina Historical Review 27 (1950, pp. 482-490) It appears that James Curry was arrested and imprisoned by civil authorities due to the “assault and battery” charges against him.23Account from the New York Tribune Raleigh correspondent in the Lewiston [Maine] Evening Journal, August 9, 1865 The outcome of this heinous attack is not known, nor is it clear whether Curry was convicted of the charges against him or was able to find his relatives and “remove them North.”

A ”thrilling account”: James Curry’s narrative as one of many

Many slave narratives appeared in print in the nineteenth century. “The Narrative of James Curry,” which Rhode Islander Elizabeth Buffum Chace published in the Liberator in January 1840, was an early one. Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself, a full-length book first came out in 1845, five years after James Curry’s narrative was published. Abolitionist Lydia Maria Child assisted Harriet Jacobs in her Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Written By Herself that was published in 1860. A project at the University of North Carolina has recently collected hundreds of books, articles, and pamphlets of North American slave narratives, many published during the nineteenth century, including Chace’s “The Narrative of James Curry, A Fugitive Slave.”24Curry’s narrative is reprinted in John W. Blassingame, ed., Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 128-144. Blassingame refers to the Narrative as a “speech” by Curry rather than a printed narrative Chace’s assistance in publicizing James Curry’s story was an early contribution to slave narrative literature. In her Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, Chace said that publishing James Curry’s “thrilling” story as one of the highlights of her thirty-year involvement in the radical antislavery movement.25Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 23

Terms:

Narrative: an account or a story

Abolitionist: someone who opposes slavery and works to end it

Bondage: another name for slavery

Slave names: to assert their freedom and to avoid capture when they came North, freedom seekers often changed the names they bore while enslaved

Galvanized: energized

Freedom Seekers: freedom seekers are enslaved individuals who liberated themselves from enslavement. You may see the term “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” used in older documents or texts. Recent scholarship acknowledges that “freedom seekers” or “self-emancipated” are preferred terms to use since the other terms places the individual in a lawbreaking context, or one deserving of capture and punishment. See https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/language-of-slavery.htm for more information

Dictated: told to someone

Literacy: the ability to read and write

Surreptitiously: secretly

Cultivated: grew

Expropriate: to take something that isn’t one’s own

Trauma: a horrible experience that leaves a deep, negative impression that stays with a person

Artisan: a person who makes and creates fine work by hand

Chastisement: punishment

Drove: a crowd or group, usually used for animals like sheep or cattle

Predominant: the most dominant

Negro: a term used to describe people of African descent or with dark-colored skin. In the past, this word was used often whereas it is now often considered disrespectful. However, some people still self-identify with this term. You may also come across the terms African American, Black, person of color, colored person, or colored. Colored person or colored are also considered outdated terms

Impelled: pushed by inner motives

Eradicate: to do away with

Famished: starving

Heinous: hateful

Questions:

Although Elizabeth Buffum Chace aided James Curry while she was living in Massachusetts and not Rhode Island, why do you think we thought it was important to share his story in this module? Why do we know so much about James Curry? What insights does his story give us into the lives of the enslaved and the deciding factors and risks they faced in seeking freedom?

What familial connections are mentioned in James Curry’s narrative? What happened to those people? Did James reunite with all of them after finding freedom? What does this story tell us about how the institution of slavery affected families?

What happened to Curry when he tried to find his family after the Civil War? Do we know what happened to Curry after this incident?

- 1“North American Slave Narratives,” introduction by William L. Andrews, accessed March 2, 2011 [link]; Frances Smith Foster, Witnessing Slavery: The Development of the Ante-Bellum Slave Narratives (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994

- 2See footnote about Cary’s “Runaway” Advertisement below.

- 3Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E. L. Freeman, 1891), 27

- 4“Narrative of James Curry, A Fugitive Slave,” Liberator, January 10, 1840; on William Lloyd Garrison, see Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000)

- 5Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Her Environment (Boston, W.B. Clarke, 1914), 71

- 6Malcolm Lovell, ed., Two Quaker Sisters (New York: Liveright, 1937), 136

- 7Person County is located in the north-central part of the state, along the border of Virginia

- 8Moses Chambers genealogical profile [link]

- 9Moses Chambers’ “Runaway” advertisement published in July 1837, listed Curry (or “Cary”) as “about 22 years of age.” N. C. Runaway Slave Advertisements, Accessed March 2, 2021 [link]

- 10Curry never named his mother in the Narrative. However, a relative of his enslaver identifies James as “one of Lucy’s boys”

- 11In a “summary” of James Curry’s “Narrative,” Erin Bartels Butler writes that James Curry’s father was “sold into slavery” after leaving North Carolina. Accessed March 10, 2021 [link]

- 12Judge Duncan Cameron (1777-1853) was a lawyer, judge, banker and legislator. His family was among the largest landholders in North Carolina and owned plantations in Alabama and Mississippi as well.

- 13Sydney Nathans, To Free A Family, The Journey of Mary Walker (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012); accessed March 1, 2021

- 14On a website noting Cameron’s prominence as a large plantation owner, lawyer, legislator, and in North Carolina, it is noted that “Cameron’s legacy in Ohio is much different. A slave who escaped to Salem, Ohio, with the assistance of Quakers, told a story about Cameron, which is not known in NC [North Carolina] today. Apparently, when Cameron walked the streets of Raleigh or Hillsborough and saw a slave, he would hit the slave on the top of the head with the brass ball on his cane as a reminder of the status of blacks. This story has made it into the underground railroad annals in Ohio, but has not made it back to NC.” Accessed February 28, 2021 [link]

- 15Moses Chambers, James Curry’s enslaver, published an advertisement entitled “Ranaway” in the Milton, N.C. Spectator of July 11, 1837. Dated June 20, 1837, Chambers’s notice offered a $50 reward for “three Negro boys, CARY, HENRY, and ALEXANDER” who had left his premises on June 14th. “Cary” was James Curry, described by Chambers as “about 22 years of age, light complected, about 5 feet 8 or 10 inches high, no marks recollected.” After giving a physical description of “Alexander” and “Henry,” Chambers offered the monetary reward “for the apprehension of said negroes and delivery in any jail in the United States, so that I can get them. All the boys can read and write tolerably well, and it is likely they may have free passes and will try to make their way to some free State.” N. C. Runaway Slave Advertisements, Accessed March 2, 2021 [link]

- 16The capitalization suggests that Chace could be referring to the Quakers

- 17In Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s draft of a letter to James Curry, dated January 15, 1840, Chace wrote that Curry had left “more than one year ago.” Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1:70

- 18Curry’s letter informing them of his safe arrival in Canada was sent to Richard C. French, an abolitionist colleague from Fall River. (Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 70; Edward Stowe Adams, Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River, and the Operation of the Underground Railroad (Fall River, Mass.: Fall River Historical Society Press, 2017), 29

- 19Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1:70-71. Wyman refers to the version of Chace’s January 1840 letter as a “draft” that was “unaddressed.” It is not known if it was ever sent. It appears that James Curry left Fall River on or after the date of the Narrative (September 20, 1838) and before February 1839, as Chace mentions that two of her children had died (“Death has twice entered our dwelling”) since Curry left. Nine-year-old George Chace died on February 25, 1839; his younger sister, Adelia, died of scarlet fever in August. Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 1: 70-71; on her children’s deaths, see ibid, 43, and Elizabeth Buffum Chace journal and miscellaneous papers, Elizabeth Buffum Chace Family Papers, Ms, 89:12, Brown University

- 20F. H. W. [Frances Harriet Whipple McDougall], ed., Pawtucket Juvenile Emancipation Society, The Envoy from Free Hearts to the Free (Pawtucket, R. I.: P. W. Potter, 1840)

- 21The National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 19, 1865

- 22William Holden to Thomas Ruger, July 27, 1865, Ruger to Holden, August 1, 1865, Horace Raper, ed., The Papers of William Woods Holden, 1841-1868, vol. 1 (North Carolina Department of Archives and History), 2000, accessed May 12, 2020 [link]; William W. Holden to Thomas Ruger, August 8, 1865, in Elizabeth Gregory McPherson, “Letters from North Carolina to Andrew Johnson (Continued),” The North Carolina Historical Review 27 (1950, pp. 482-490)

- 23Account from the New York Tribune Raleigh correspondent in the Lewiston [Maine] Evening Journal, August 9, 1865

- 24Curry’s narrative is reprinted in John W. Blassingame, ed., Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 128-144. Blassingame refers to the Narrative as a “speech” by Curry rather than a printed narrative

- 25Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, 23