The Struggle for Woman Suffrage in Rhode Island

Essay by Elizabeth C. Stevens, Ph.D., Editor, Newport History

The struggle to achieve women’s right to vote in the state began in earnest shortly after the Civil War. Rhode Island women who had been active in the antislavery movement decided to use their organizing skills to gain the vote. They wanted to use the power of their ballots to make a difference in their cities and towns by fully participating in elections.

In Rhode Island, the right to vote had been restricted for men, too. In the 1800s, many male residents were prevented from voting because they did not own property, or were not native-born citizens, or because they were African-Americans. Some restrictions on male voters were lifted by the Bourn Amendment,1See EnCompass essay about the Bourn Amendment in the Immigration chapter [link] passed by the Rhode Island legislature in 1888.

In Rhode Island, two women took the lead in the woman suffrage fight. Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis was a well-known health educator and activist who taught anatomy classes for women before the Civil War. She moved to Rhode Island in 1849 when she married Thomas Davis, Providence businessman and politician.2“Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis,” National Women’s Hall of Fame, accessed June 14, 2019 [link]

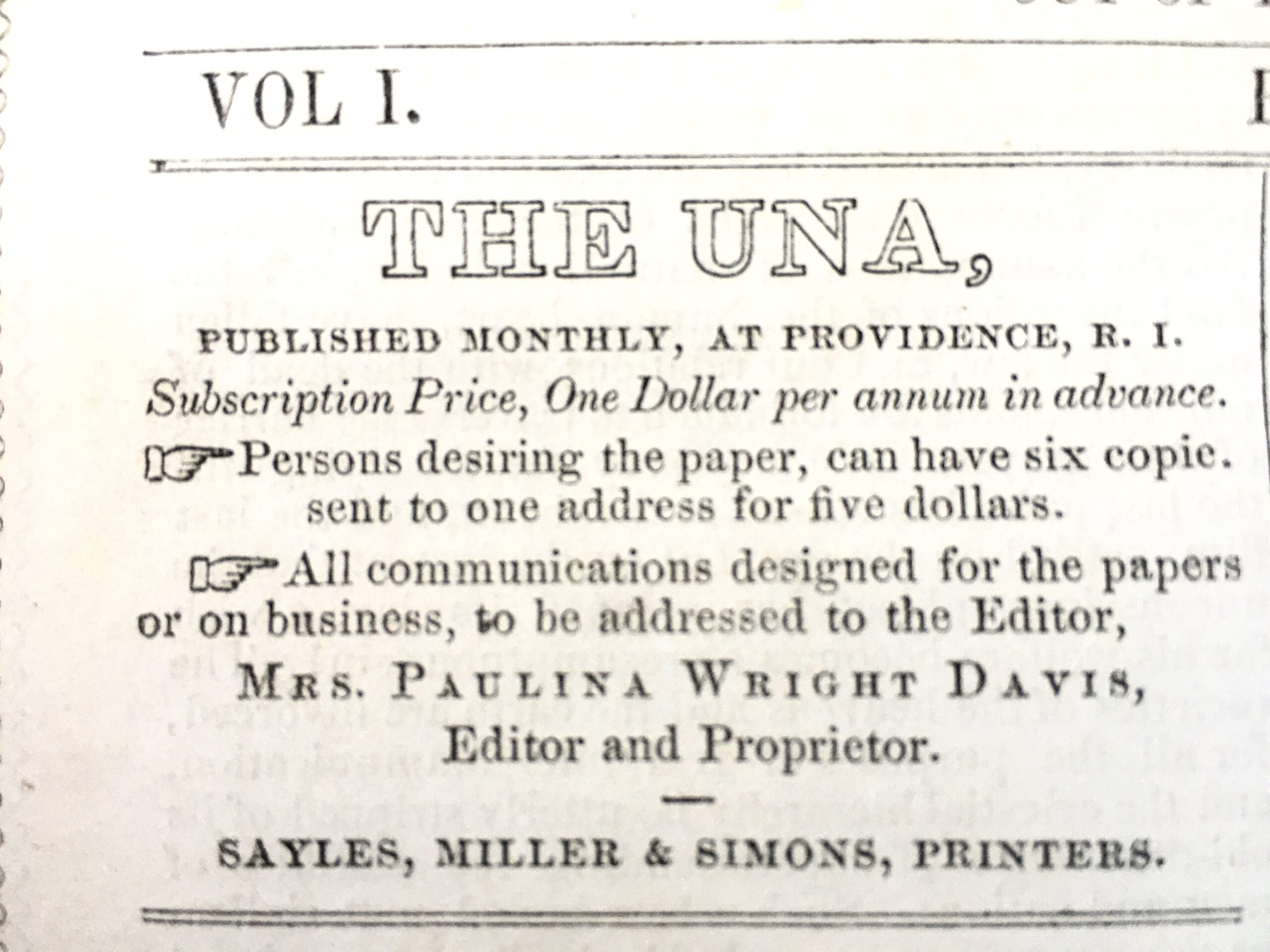

In 1850, Paulina Wright Davis chaired the first national women’s rights convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. The convention was attended and supported by a number of women from Rhode Island. Those who attended called for “Equality before the Law, without distinction of Sex or color.” Paulina Wright Davis was subject to scorn and ridicule for promoting the idea of women’s rights. Some newspapers made fun of the Worcester gathering by calling it a “hen convention.” In the 1850s, Davis published a newspaper in Providence called The Una, devoted to the rights of women.3Paulina W. Davis, comp., A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement, for Twenty Years, with the Proceedings of the Decade meeting held at Apollo Hall, October 20, 1870, From 1850 to 1870. With an appendix containing the history of the movement during the Winter of 1871, in the National Capitol. (New York: Journeymen Printers’ Co-operative Association, 1871), 12-16

The Una

Read about Paulina Wright Davis and her publication, The Una, here

Elizabeth Buffum Chace joined with Paulina Wright Davis in the struggle for women’s suffrage. Chace had been an active antislavery worker before the Civil War. Her house in Valley Falls (today part of Central Falls) was a stop on the Underground Railroad. She and her husband, Samuel Chace, helped people fleeing enslavement in the South. She hosted many well-known antislavery speakers who came to Rhode Island, including Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass. Antislavery workers were unpopular, and Elizabeth Buffum Chace knew what it was like to be scorned and derided for her activism. Once, when she was on her way to hear an antislavery speaker in Valley Falls, she and her children were pelted with rocks while insults were hurled at them.4Elizabeth C. Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman, A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist and Workers’ Rights Activism (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003), 43-73

Paulina Wright Davis and Elizabeth Buffum Chace were friends before and during the Civil War. Together, they helped to found the New England Woman Suffrage Association with other former antislavery workers in Boston in 1868. Then, Davis and Chace turned their sights on their home state of Rhode Island. They called for a convention to be held in downtown Providence to form a statewide association that would be devoted to working to get the vote for women. The convention was held on December 11, 1868, in Roger Williams Hall.5Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace 1806-1899, Her Life and Its Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 1:309-311

Paulina Wright Davis became the president of the newly formed Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association (RIWSA). Elizabeth Buffum Chace was head of the Executive Committee. Davis and Chace believed that if women could vote, they could help solve problems brought about by rapid industrialization, immigration, and financial downturns of the post-Civil War era. Davis and Chace also felt that women were equal to men and deserved every right that men legally possessed—the right to an education, to control their finances, and to participate in the political process by voting.

Women Employees Playing Baseball

Read about how labor rights tied in with women's suffrage here

A small group of women and men joined RIWSA in 1868. Their goal was to gain an amendment to the state constitution that would explicitly give voting rights to women. The Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association was part of a national coalition of women’s suffrage groups from many states that were seeking the vote for women at this time.

Sadly, in 1869, there was a painful split in the national organization about whether to support the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would give the vote to African-American men. One faction headed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who were friends of Paulina Wright Davis, did not support the Fifteenth Amendment because it did not give the vote to women. Paulina Wright Davis tried to convince her good friend, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, to oppose the amendment, but Chace decided to support it. Paulina Wright Davis left the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association because of this issue, and the national movement split into two branches, the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, based in New York, and the American Woman’s Suffrage Association, based in Boston, of which the RIWSA was a part. The two national organizations did not get back together until the early 1890s.6Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment,1: 318-320

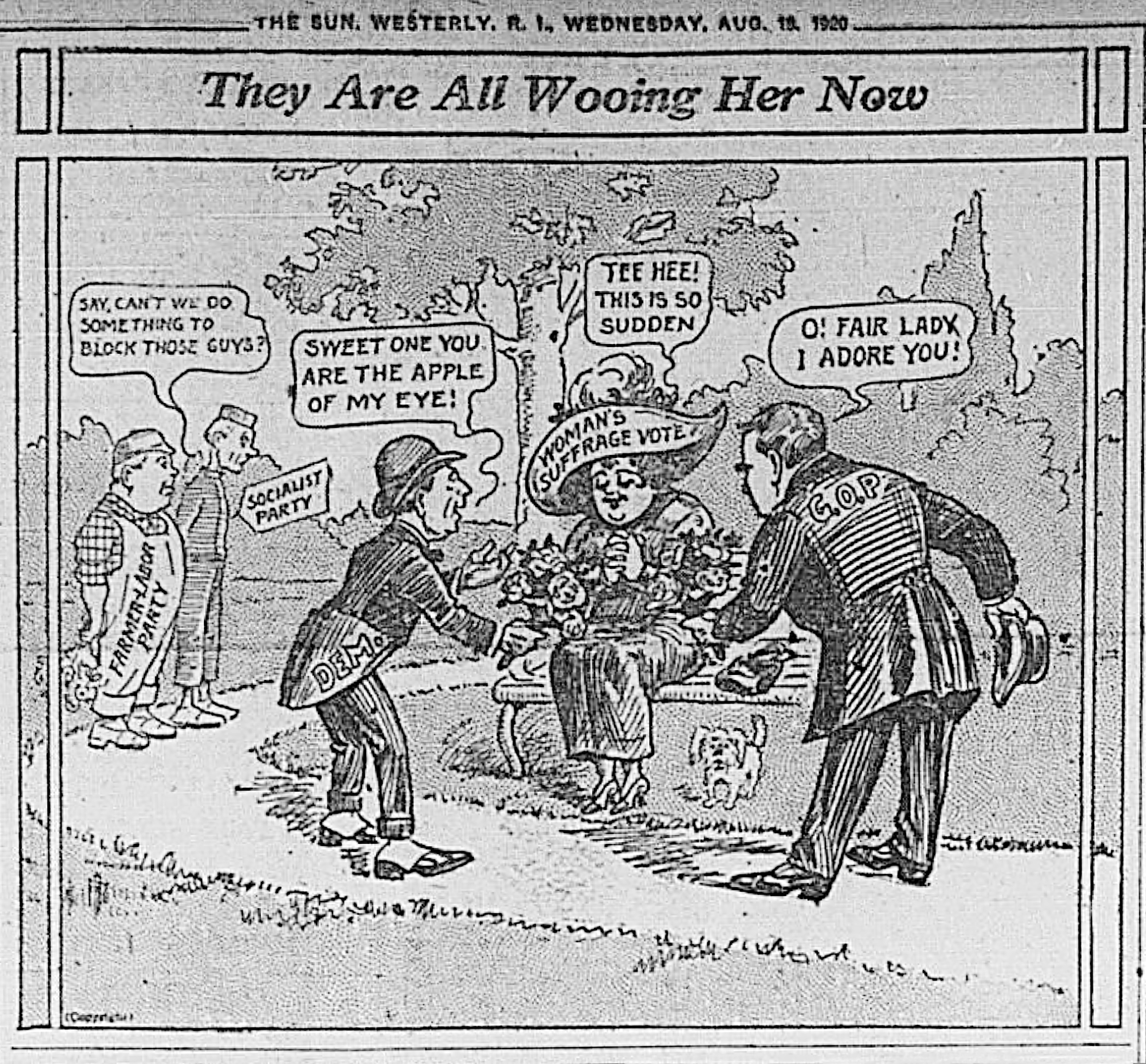

Political Cartoon from a Rhode Island Newspaper

Read about the 19th Amendment and how it was passed here

Woman suffrage activists in Rhode Island worked very hard during the 1870s and 1880s. They asked their friends, neighbors, and even strangers to sign petitions urging the state legislature to debate the subject of woman suffrage. They organized meetings with inspiring speakers and pressured representatives in the state legislature to take up the subject of votes for women. The suffrage workers testified at hearings at the R.I. State House. They also published articles and letters in newspapers in support of women’s voting rights.

These woman suffragists were ridiculed and treated poorly by newspaper writers, state legislators, and citizens. Their cause seemed hopeless. They would have to convince the legislature to hold a statewide referendum on women suffrage and then a majority of the male voters of the state would have to vote “yes” in the referendum. Nevertheless, the Rhode Island Woman’s Suffrage Association pressed on with its petition drives and meetings to raise the issue’s profile.7Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 78-91; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage (Rochester, N.Y.: Charles Mann, 1887), 3:343-350

By 1884, the suffragists had garnered enough influence to convince the Rhode Island legislature to allow them to hold their annual meeting at the Rhode Island statehouse (what is now called the “Old Statehouse”) on Benefit Street in Providence. Such luminaries as Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony attended the gala gathering. Elizabeth Buffum Chace proclaimed that the push for women’s suffrage in the state had made progress but that there was much more work to be done.8Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment, 2: 188-191; Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 148

If the 1884 convention was a symbolic affirmation of progress, the actual proof came when the Rhode Island legislature agreed to hold a state referendum on woman suffrage in the spring of 1887. The suffrage workers had but a few weeks to mount their statewide campaign. A headquarters, open for more than twelve hours a day, was established in the Butler Exchange in downtown Providence. Some ninety-two meetings were held in parlors, churches, and halls across the state in virtually every city and town. In the days before the vote, suffragists organized mass rallies in downtown Providence in support of the amendment. The RIWSA published its own newspaper, The Amendment, to convince the male voters of Rhode Island to support women’s suffrage.9Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 147-152

The results of the 1887 amendment campaign were disappointing. Despite the urgent and exhausting campaign waged by RIWSA, the woman suffrage amendment to the state constitution failed to pass by even a close margin (6,889 men voted in favor and 21,957 men voted against).10Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., The History of Woman Suffrage, 1883-1900, (Rochester, N.Y.: Susan B. Anthony [1902]), 4:909-912)

Girls City Club Logo

Read about women's organizations here

Despite the difficult struggle to gain the vote for women in Rhode Island, the suffragists allied with other women’s organizations to bring about change. During the 1870s and 1880s, there were many women’s activist organizations in Rhode Island. The largest was the Rhode Island Christian Temperance Union (RIWCTU) which had chapters in almost every town in the state. The RIWCTU wanted the state legislature to outlaw the sale of liquor because they believed that excessive drinking led to poverty and domestic violence. Women’s clubs were also organized in Rhode Island at this time. The women’s clubs provided an educational and social environment for women who had not had access to higher education. The Women’s Educational and Industrial Union provided support for working women. Young women factory workers joined labor unions to push for women worker’s rights. Representatives from these organizations and other women’s groups banded together to form the Rhode Island Council of Women to work together on issues of concern to women.

The Rhode Island Woman’s Suffrage Association, realizing that the struggle for the vote might take years to accomplish, worked together with other women’s organizations on many issues that were crucial to women’s lives. For example, the RIWCTU spearheaded an effort in the 1870s to place a female police matron in every city jail in Rhode Island. The suffragists aided their successful efforts. The WCTU supported the suffragists in their efforts to get the vote for women. In the early 1890s, representatives of women’s organizations in Rhode Island banded together to push for legislation that would help women factory workers. Suffrage leader Anna Garlin Spencer was a critical supporter of that effort. Even if women could not vote at this time, they found that working together and cooperating, they could influence legislation that would have a beneficial effect on women’s lives.11Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 86-90,152-53,158-159

In the 1890s, African-American women in Rhode Island formed clubs to combat racial discrimination and its effects in employment, education, housing and other areas. In the Reconstruction era, African-American women were not welcomed in the clubs and associations formed by white women in Rhode Island.

Many members of the African-American women’s clubs also supported woman suffrage. In 1895 delegates from African-American women’s clubs, like the Woman’s Newport League, joined together with representatives from similar clubs all over the country to form the National Federation of Afro-American Women’s Clubs (later, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs). Two Rhode Island women, Mary H. Dickerson of Newport and Hannah E. Greene of the Working Women’s Club of Providence, were official delegates to the national convention in Boston in 1895. Mary Dickerson, who was active in the creation of the national organization, was voted the first vice-president of the National Federation of Afro-American Women’s Clubs. Dickerson, who was a dynamic organizer, also headed the Rhode Island Union of Colored Women’s Clubs, formed in 1903, which included at least eleven clubs from around the state.12Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 103-104; Richard C. Youngken, African-Americans in Newport: An Introduction to the Heritage of African-Americans in Newport, Rhode Island 1700-1945 (R.I. Preservation and Heritage Commission and R.I. Black Heritage Society, 1995), 34; A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of the United States of America as Contained in the Minutes of the Convention held in Boston, July 29, 30, 31, 1895, and of the National Federation of Afro-American Women held in Washington, D.C., July 20, 21, 22, 1896 (Published 1902), 10, 29

Elizabeth Buffum Chace, the leader of the Rhode Island woman suffrage movement, died in December 1899 at the age of ninety-three. At her memorial service, younger Rhode Island suffrage workers, like Anna Garlin Spencer, a minister, paid tribute to Chace’s tenacity and activist skills.13Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 195-97 After Chace’s death, the suffrage movement in Rhode Island languished for a few years although the faithful members of the RIWSA continued to have meetings with dynamic speakers like Susan B. Anthony and Julia Ward Howe, who was also a well-known activist.14Sara M. Algeo, The Story of a Sub-Pioneer (1925), 95, 97

Bertha Higgins’s House

Read about Bertha Higgins here

The formation of a College Equal Suffrage League chapter in Rhode Island in 1907 gave an enormous boost to the woman suffrage effort in the state. The College Equal Suffrage League was organized by college women and had chapters across the country. Working hand-in-hand with RIWSA, the younger women of the R.I. College Equal Suffrage League brought new energy and new members to the suffrage fight. A wealthy patron of the women’s suffrage cause, Alva Belmont, created welcome publicity and financial support when she opened her mansion, Marble House, for a series of woman suffrage events in Newport in 1909.15Ida Husted Harper, ed., The History of Woman Suffrage 1900-1920 (National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922), 6: 567

After the turn of the century, woman suffragists began to change their goal from pushing for an amendment to state constitutions to advocating for an amendment to the federal (national) constitution. In 1908, Rhode Island woman suffrage workers gathered thousands of names on a petition to Congress on behalf of the federal amendment.16Harper, ed., History of Woman Suffrage, 1900-1920, 6:566-67

The formation of a Woman Suffrage Party in Rhode Island in 1912 also bolstered the campaign to win women the vote. Sara Algeo, a leader in the early-twentieth-century suffrage movement in Rhode Island, later remembered, “The time had come when iron entered the soul of our women, and we resolved to gain our point whatever the cost.”17Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 123, 162, 170

African-American women in Rhode Island provided key support for woman suffrage when the Rhode Island Union of Colored Women’s Clubs endorsed the Woman Suffrage Party in 1913. With dynamic leaders Mary E. Jackson and Bertha Higgins, the Union of Colored Women’s Clubs was the largest woman’s organization in Rhode Island to come out for woman suffrage.18Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 162-65; Terborg-Penn, African-American Women, 103-104; Elisa Miller, “Biography of Bertha Higgins 1872-1944,” accessed June 15, 2019 [link] In 1915, the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association, the College Equal Suffrage League and the Woman Suffrage Party merged to form the Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association.19Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 242-43

By the nineteen-teens, with women already voting in some western states, male politicians of major political parties saw that women could provide crucial support in elections. Despite progress in Rhode Island, there was still resistance. In 1913, a Rhode Island legislator demanded to know why a bill favoring presidential suffrage for women was wasting the legislators’ “valuable time, and threw it on the floor and stamped on it, saying, ‘I will kill woman suffrage.’” Nevertheless, Rhode Island women gained the right to vote in presidential elections in a bill that passed the legislature in April 1917.20Harper, ed., Woman Suffrage, 1900-1920, 6: 575

Almost three years later, on January 6, 1920, the R.I. legislature ratified the nineteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution that guaranteed the vote to women. It became law in August 1920 when the Tennessee legislature approved the woman suffrage amendment by one vote. Even before they had time to celebrate, woman suffragists in Rhode Island formed the United League of Women Voters. The new organization, led by suffrage activists like Sara Algeo and Bertha Higgins, was a non-partisan group devoted to educating female voters to exercise their hard-won right to vote in Rhode Island elections. One hundred years later, the League of Women Voters is still active in Rhode Island.21“Historical Note,” Records of the League of Women Voters of Rhode Island,” Mss. 21, Rhode Island Historical Society Library; Ida Husted Harper, ed., History of Woman Suffrage 1900-1920 (National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922), vol. 5: 683-701, and vol. 6: 575-577; Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 258-259

Terms:

Suffrage: the right to vote in local, state and federal elections

Amendment: a change or addition to a law, regulation, or constitution

Petition: a written appeal to an authority that is signed by a number of people

Referendum: when a particular question is put to the voters of a state or town to see which side is favored by the majority of voters

Ratify: to approve an amendment to a constitution

Questions:

Why do you think Paulina Wright Davis was subject to scorn and ridicule for promoting the idea of women’s rights?

Who did the women suffragists have to convince in order to pass a referendum in the state granting women the right to vote? When did the state legislature hold the first referendum, and what were the results?

Some women were against women’s suffrage. Research and write about their reasonings.

What were the goals of the women’s organizations in the struggle for women’s suffrage? What are two of these organizations, and what did they accomplish?

What was the timeline for Rhode Island women to gain suffrage at the state level and finally nationally? What major failures and successes happened along the way to gaining women’s suffrage?

One hundred years later, there are still members of our society who do not have suffrage. Research and write about who they are and what is preventing them from gaining full suffrage.

- 1See EnCompass essay about the Bourn Amendment in the Immigration chapter [link]

- 2“Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis,” National Women’s Hall of Fame, accessed June 14, 2019 [link]

- 3Paulina W. Davis, comp., A History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement, for Twenty Years, with the Proceedings of the Decade meeting held at Apollo Hall, October 20, 1870, From 1850 to 1870. With an appendix containing the history of the movement during the Winter of 1871, in the National Capitol. (New York: Journeymen Printers’ Co-operative Association, 1871), 12-16

- 4Elizabeth C. Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Lillie Chace Wyman, A Century of Abolitionist, Suffragist and Workers’ Rights Activism (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003), 43-73

- 5Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace 1806-1899, Her Life and Its Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 1:309-311

- 6Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment,1: 318-320

- 7Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 78-91; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage (Rochester, N.Y.: Charles Mann, 1887), 3:343-350

- 8Wyman and Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Her Life and Its Environment, 2: 188-191; Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 148

- 9Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 147-152

- 10Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., The History of Woman Suffrage, 1883-1900, (Rochester, N.Y.: Susan B. Anthony [1902]), 4:909-912)

- 11Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 86-90,152-53,158-159

- 12Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 103-104; Richard C. Youngken, African-Americans in Newport: An Introduction to the Heritage of African-Americans in Newport, Rhode Island 1700-1945 (R.I. Preservation and Heritage Commission and R.I. Black Heritage Society, 1995), 34; A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of the United States of America as Contained in the Minutes of the Convention held in Boston, July 29, 30, 31, 1895, and of the National Federation of Afro-American Women held in Washington, D.C., July 20, 21, 22, 1896 (Published 1902), 10, 29

- 13Stevens, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, 195-97

- 14Sara M. Algeo, The Story of a Sub-Pioneer (1925), 95, 97

- 15Ida Husted Harper, ed., The History of Woman Suffrage 1900-1920 (National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922), 6: 567

- 16Harper, ed., History of Woman Suffrage, 1900-1920, 6:566-67

- 17Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 123, 162, 170

- 18Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 162-65; Terborg-Penn, African-American Women, 103-104; Elisa Miller, “Biography of Bertha Higgins 1872-1944,” accessed June 15, 2019 [link]

- 19Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 242-43

- 20Harper, ed., Woman Suffrage, 1900-1920, 6: 575

- 21“Historical Note,” Records of the League of Women Voters of Rhode Island,” Mss. 21, Rhode Island Historical Society Library; Ida Husted Harper, ed., History of Woman Suffrage 1900-1920 (National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922), vol. 5: 683-701, and vol. 6: 575-577; Algeo, Sub-Pioneer, 258-259