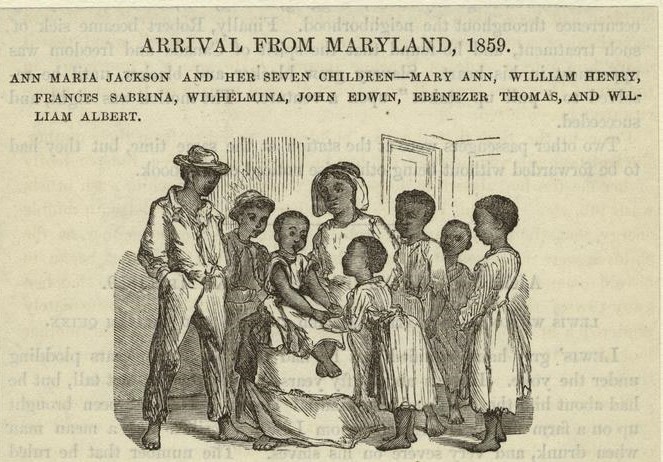

Engraving of Ann Maria Jackson and her Seven Children

Anna Maria Jackson, a woman enslaved in Delaware, successfully escaped with seven children—the youngest was three or four and the oldest was sixteen. The children’s names were Mary Ann, William Henry, Frances Sabrina, Wilhelmina, John Edwin, Ebenezer Thomas and William Albert. These children were to have been sold “at public sale” and their mother, who had already lost two children when her enslaver sold them, risked the perils of escape, rather than be separated from her remaining offspring.

The digital copy of the image can be found at the New York Public Library’s digital collections.

Children and Teenagers in the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island

Essay by Elizabeth C. Stevens. Editor, Newport History

“It was not easy. . .to protect children while on the run”: Freedom-seekers brought their children

The story of the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island is not just about adults. Children who were born to an enslaved mother were considered the property of her enslaver from the moment they were born. Children and teenagers who had been enslaved also sought freedom from bondage, usually with their families, sometimes following routes to and through Rhode Island. Some Rhode Island families who assisted freedom seekers had children and teenagers living at home. Sometimes these young people helped in the work of their parents. At the very least, Rhode Island children whose parents helped formerly enslaved people were also required to be silent and keep secrets about their parents’ work. Children who grew up in antislavery families who were involved in the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island had unusual childhoods.

Although many self-emancipated people who came North seeking freedom were single men or couples, records show that families with children also made the perilous journey to freedom. In their book about freedom seekers, John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger observe, “it was not easy to feed, clothe, care for and protect children while on the run. The physical burden of carrying babies or youngsters four or five years of age was extreme, while seven- or eight-year-olds had trouble keeping up and often tired quickly.”1John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 64 Anna Maria Jackson, a woman enslaved in Delaware, successfully escaped with seven children—the youngest was three or four and the oldest was sixteen. The children’s names were Mary Ann, William Henry, Frances Sabrina, Wilhelmina, John Edwin, Ebenezer Thomas and William Albert. These children were to have been sold “at public sale” and their mother, who had already lost two children when her enslaver sold them, risked the perils of escape, rather than be separated from her remaining offspring.2William Still, The Underground Rail Road A Record (Philadelphia: Peoples Publishing Company, 1871), 512-514

The few accounts we have of freedom seekers passing through Rhode Island in the mid-nineteenth century record families with children. In one of her yearly reports, Amarancy Paine, a young woman who ran the R.I. Anti-Slavery Society office in the Arcade in downtown Providence, noted that in the previous year, “at one time there was a company of eight persons, five of them children,” assisted by the R.I. Society.3William F. Davis, Saint Indefatigable: A Sketch of the Life of Amarancy Paine Sarle (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1883), 40 Elizabeth Buffum Chace who sheltered freedom seekers in her Valley Falls home, remembered one instance when a mother with three boys under the age of fourteen was forced to take refuge at the Chace home. The mother and her children, who had been living in Fall River for several years, remained in Valley Falls for three days while waiting for an older son to join them as they fled from possible re-enslavement.4Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R. I.: E. L. Freeman, 1891), 35-38

Their parents might go to prison: children as Underground Railroad workers

Many men and women who sheltered freedom seekers in their Rhode Island homes in the decades before the Civil War had children living at home. Isaac and Sarah Casey Rice in Newport, for instance, had eight children, some of whom still lived in their home in Newport in 1850, including 20-year-old Isaac Rice, Jr., his younger sisters eighteen-year-old Susan and sixteen-year-old Hannah and the youngest, George Rice, who was eight.5Federal Census, Newport, R.I., 1850; Isaac Rice homestead, Thomas Street, Newport, Accessed April 14, 2021 [link]; “Isaac Rice,” in Rhode Island African American Data, Accessed April 14, 2020 [link] The daughters of Sarah Harris and George Fayerweather, Sarah, Mary and Isabella, were in their late teens when the family moved to Kingston in 1855. And, their younger brothers, George and Charles were fourteen and ten, respectively.6Federal Census, New London, Ct., 1850; Federal Census, Kingston, R.I., 1860; Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York: New York University Press, 2019), chapter 1 With freedom seekers staying at their homes, these children would have been aware that the safety, and even lives, of their guests depended on keeping silent about their parents’ actions. The young people also had some part in helping to care for freedom seekers, if only because household arrangements were affected by the arrival of strangers on their doorstep. Even Rhode Island abolitionist children who were younger, like Elizabeth (born about 1850) and Charles Perry (born about 1851), the children of Charles and Temperance Perry of Westerly whose house on Margin St. was a safe house on the Underground Railroad, had to be aware of their parents’ activities in sheltering freedom seekers.7Federal Census, Westerly, R.I., 1860

Samuel, Arnold, Lillie, Edward and Mary Chace, who ranged from three to fourteen years old in the mid-1850s, were raised in an abolitionist household in Valley Falls. After the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850, Samuel and Elizabeth Chace told their children that it was possible that “the constables” might “come and carry” their parents “off to jail” for harboring and aiding “fugitives.” Lillie remembered that she and her siblings “promised to be very good if such a thing should occur,” and she added, half-joking, that she and her brothers were so excited by the prospect of their parents being jailed that they might have “almost hoped” their parents would go to prison. The Chace children “felt a great admiration for an Irishman who did chores on the place,” who had apparently declared that “he would fight before he would allow officers of the law to take a fugitive slave.”8Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” Atlantic 64 (August 1889):167-68)

“Should the Fourth of July be celebrated while slavery existed?”: Abolitionist childhoods in Rhode Island

Elizabeth Buffum Chace raised her children to be antislavery workers. In childhood, they read The Liberator, children’s versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (originally published in 1852), and other antislavery books and magazines written for children. They attended abolitionist meetings and lectures with their mother, mingled with noted antislavery speakers who visited their home such as Charles Lenox Remond, Sojourner Truth, and Wendell Phillips, and were even pelted with rocks by a pro-slavery mob when they were returning from an antislavery meeting in Valley Falls at the start of the Civil War.9Wyman, “From Generation to Generation”; Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Her Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 1:215-16; Elizabeth C. Stevens, “Mothering as a Subversive Activity in Nineteenth-Century Rhode Island,” Quaker History 84 (Spring 1995): 37-57 The Fayerweather children’s parents also subscribed to several antislavery newspapers and took their children to antislavery meetings and conventions.10Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2008), 1:187 The children of Isaac and Sarah Ann Casey Rice would have had contact with famed antislavery activists who stayed at their home in Newport, including Frederick Douglass, Charles Lenox Remond, and Henry Highland Garnet.11Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport, R.I.: Newport’s Black Museum, 1932), 30

Some children of Underground Railroad families even attended special schools to enhance their antislavery training. Fifteen-year-old Sammy Chace and thirteen-year-old Arnold Chace attended the Hopedale Home School, in Hopedale, Massachusetts, not far from Rhode Island, a coeducational boarding school open to both boys and girls. Among Samuel and Arnold’s classmates were other children of Rhode Island antislavery activists who also participated in the Underground Railroad. George Rice from Newport attended with the Chace boys, as did Serena Downing, who was also from Newport. She was the daughter of George T. Downing, a civil rights activist and a key operator on the Underground Railroad in New York. He is believed to have continued his work with the Underground Railroad when he moved to Rhode Island in the 1840s. The Chace boys were pupils at the short-lived school from 1858-1860.

The Hopedale Home School was organized and run by utopian reformers. In their classes at their unorthodox school, the Chace, Rice and Downing children not only studied mathematics, science and literature, but as part of their regular curriculum, debated such issues as whether it would be wrong to tell a lie to a slaveholder in order to protect an escaped slave, or whether the Fourth of July should be celebrated while slavery existed in the country. They also acted out scenes illustrating the evils of slavery.12Elizabeth C. Stevens, “A Symmetrical, Harmonious Substantial Character”: Schools for Abolitionist Children in Nineteenth-Century New England,” Schooldays in New England, 1650-1900, The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, June 19-21, 2015, 59-72

Other children of Rhode Islanders who opposed the Fugitive Slave Law, such as Martha Browning, the eighteen-year-old daughter of Peter and Aurelia Browning who was the oldest of five siblings, signed petitions asking the state legislature to condemn the law.13The “colored citizens of Providence” to the Honorable General Assembly of the State of R.I. (Petition to Urge the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, February 1851, R.I. State Archives Twenty-year-old Isaac Rice jr. whose father was a key Underground Railroad agent in the state, signed the Newport petition as did seventeen-year-old Mary Jane Smith.14“The colored citizens of Newport” to the Honorable General Assembly of the State of R.I. (Petition to Urge the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, February 1851, R.I. State Archives)

“Some lacking sympathy might see them and have them arrested”: Account of a child in Pawtucket.

Two Rhode Island men remembered their own and their families’ involvement with the Underground Railroad many decades later. One was Samuel Pidge, who grew up in his grandfather’s house in Pawtucket. Pidge, who was born in 1855, shared his memories with a reporter for the Pawtucket Times in 1934 of the work of his father, James Pidge, and grandfather, Ira Pidge, in the Underground Railroad. Samuel recalled, “episodes of his boyhood as he assisted his father and grandfather to shelter and hide. . .fugitives in the Pidge horse stables.” He was around five years old at the time. The Pidge home was located on Pawtucket Avenue between Pidge Avenue and Lafayette Street. The Pawtucket Times asserted that “friendly Quakers would direct [the freedom seekers] to the Pidge house, then a farmhouse but formerly a post road tavern.”

Samuel remembered that the fugitives spent the night in “a large stable. . . in ‘Pidge Lane’ about four hundred feet from the Pidge farmhouse.” Samuel’s family feared that if the freedom seekers slept in their house, “someone lacking sympathy might see them and have them arrested for a reward.” Samuel would “peep fearfully at the ‘black men’ hidden in his father’s barn, and wonder who taught them the kind of English language they used in speaking to him.” The eighty-year-old Pidge recalled, “two big men fugitives and one woman, who were hidden in the barn at different times. [T]heir southern accent was too much for me and I could hardly understand a word they spoke.” Members of the Pidge family brought food from the house to the travelers resting in the barn. Pidge claimed that the freedom seekers “usually arrived in the early morning, before dawn,” and then ‘resumed their journey afoot when darkness again set in.’” He remembered that “the runaways carried sticks with bundles, resting on their shoulders.”15“Old Pidge House Revealed as Fugitive Slave Hideout,” Pawtucket Times, December 3, 1934, second section; Betty Johnson and James Wheaton, “Pawtucket played role in Underground Railroad,” Pawtucket Times, October 10, 1998; “Old Landmark in Path of Progress, Pawtucket Evening Times, April 11, 1906

“The excitement of the undertaking appealed to me greatly”: A teenage worker in Ashaway, R.I.

Perhaps the most vivid and dramatic recollections of a teenager’s experience with the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island came from Isaac Cundall of Ashaway (Hopkinton). In 1918, Cundall told a newspaper interviewer that his father, also named Isaac Cundall, was “an earnest worker in behalf of the fugitive slaves from the South,” as was Jacob Babcock, who owned a mill in Hopkinton.16“Jacob Babcock’s house on High Street in Ashaway was a stop on the Underground Railroad” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Cynthia Drummond, “A gateway to freedom: Hopkinton provided an important stop on the Underground Railroad,” The Westerly Sun, January 21, 2019 [link] One day, when Isaac Cundall was sixteen, he was contacted by Jacob Babcock who told him, “I have a colored man slave I want you to take away tonight.” Cundall thought he should see his father before undertaking the risky task. He recalled that, “There had been several slaves taken over our part of the ‘underground,’ and while the matter was never discussed except in the briefest possible way I had a full understanding of it.” He claimed that “ours was the first ‘station’ in Rhode Island.17Ashaway was close to the Connecticut state line, and by “first station” in Rhode Island, Cundall probably meant the first stop for freedom seekers coming from eastern Connecticut. Freedom seekers also came into the state via Westerly, and, in northern R.I., from Fall River and New Bedford to Pawtucket, Central Falls and elsewhere Where the slaves came from to us, I never knew, and I never asked. Strict secrecy was observed; what we did not know, we could not be expected to tell should anybody begin asking questions.” Isaac’s father warned him: “’Isaac, you know what this means. If you are caught, it will mean a fine of $1000 and six months in jail.’” Mr. Cundall assured his son that he and others would pay the fine, but that young Isaac would have to spend the time in jail, if caught. Isaac responded that he “was not afraid to do anything that was right.”18“Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Russell J. De Simone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad,” Accessed May 16, 2021 [link]

Recalling the incident, Cundall described an elaborate ruse that his father devised in order to deceive a family member who lived in the house, “a strong pro-Slavery man who had vowed to inform the authorities if he ever discovered the whereabouts of a fugitive slave.” After pretending to go to bed, Isaac crept out of the house as silently as possible, hitched up his father’s horses, and drove to Jacob Babcock’s house. There, he was greeted by Babcock and the freedom seeker, who expressed some concern that his fate would be put in the hands of a “mere boy.” On the journey, the pair were suddenly aware of “another horse and wagon,” coming up the road after them. Isaac asked his passenger to get out and to “hide in the bushes by the roadside.” The man did so, and Isaac jumped from the wagon and pretended to be fixing a shoe on one of the horses. The other rig arrived, driven by the county sheriff. “He asked what I was doing and where I was going,” Isaac remembered. The teenager said that his “horse had gone lame because of a lodgment in its shoe,” and that, once he had fixed it, he was going to get a doctor. The sheriff asked if Isaac had seen any other “rigs” that night, and Isaac replied that he had not. The sheriff seemed to believe Isaac’s story and left. After the lawman had gone on for a while, Isaac found his fellow traveler, and they were soon at “Mr. Foster’s in Hopkinton,” the next stop. When Isaac went into Foster’s house, his passenger ran off and hid “fearing I had taken him to the wrong house.” He was found and reassured. Although Isaac never saw the man again, he did receive word that the man had arrived in Canada.

The following year, Cundall again assisted the work of the Underground Railroad in his area when, “in broad daylight,” he helped a woman escape who was being closely pursued by her enslaver and “Sheriff Berry” of Westerly. 19Weeden H. Berry was the sheriff of Westerly for a number of years. John Livingston, Official Directory and Law Register for the United States, for the Year 1866 (New York: C.A. Alvord, 1866), 496 On his way to Babcock’s house to assist, Isaac encountered the sheriff and the woman’s enslaver, a man from Virginia. The men informed the teenager that they were searching for the unnamed woman and offering a large reward if she should be apprehended. Asked where she was, Isaac responded, “I cannot tell what I do not know.” Arriving at Babcock’s house, Isaac was told that it would be a dangerous undertaking to transport the woman in daylight as the sheriff and others were patrolling the roads in and out of the town, but that she must be “taken away” immediately.

Faced with a dangerous situation that was especially critical for the woman, Isaac concocted a plan. He took Babcock’s teenage daughter, Sarah, heavily swathed in shawls and veils, with him for a ride, knowing that they would encounter the sheriff who was patrolling the roads. They met him almost at once. The sheriff recognized Sarah and remarked on how cold it was. Isaac agreed. A short time later, the two teenagers returned to the Babcock house, again deliberately passing the sheriff and telling him that they were going back to get more garments for warmth. Back at the Babcock house, Sarah helped the endangered woman don the bonnet, dress and shawl that Sarah had been wearing, adding a “wrap” to the outfit. The “heavily veiled woman” took Sarah’s place in the wagon. When Isaac and his passenger again encountered the sheriff, Isaac greeted him and indicated that, “Now we are off,” and the sheriff apparently wished them, “Good luck.” Isaac drove the woman to “Preacher John Wilbour’s house” “beyond Hopkinton.”20The house of “Preacher John Wilbour” near Hopkinton was probably that of noted Quaker leader John Wilbur who had died in 1856. Accessed May 16, 2021 [link] Cundall later remarked that he “never felt any fear in thus piloting slaves. I was a boy, and the excitement of the undertaking appealed to me strongly.” Cundall later served in the Seventh Rhode Island regiment during the Civil War.21“Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Russell J. De Simone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad,” Accessed May 16, 2021 [link]

Children and the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island

The Underground Railroad, by its very nature, involved children. Youngsters and teenagers escaped from enslavement with their families and made the arduous and risky trek with them to freedom. In Rhode Island, freedom seekers’ children are known to have been aided by Rhode Islanders. At least one child, Henry Manton, may have been as young as five years old and without his parents when he was taken in by abolitionists in Little Compton, where he settled and lived for the rest of his life.22Margery Gomez O’Toole, If Jane Should Want to Be Sold: Stores of Enslavement, Indenture and Freedom in Little Compton, Rhode Island (Little Compton, R.I.: Little Compton Historical Society, 2016), 221, 256 Children and teenagers of Rhode Island families who worked in secret to assist freedom seekers in the years leading up to the Civil War, aided the cause in many ways—by helping with household chores, running necessary errands, and in keeping silent about their parents’ activities. In some cases, teenagers like Isaac Cundall of Ashaway in southern Rhode Island took principal roles in aiding freedom seekers to escape apprehension and re-enslavement.

Terms:

Freedom Seekers: freedom seekers are enslaved individuals who liberated themselves from enslavement. You may see the term “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” used in older documents or texts. Recent scholarship acknowledges that “freedom seekers” or “self-emancipated” are preferred terms to use since the other terms places the individual in a lawbreaking context, or one deserving of capture and punishment. See The Language of Slavery from the National Park Service for more information

Self-emancipated: enslaved people who have freed themselves from slavery

Refuge: shelter

Constables: people paid to enforce the law, like police

Harboring: sheltering

Siblings: sisters and brothers

Abolitionist: someone who worked for the elimination of slavery in the U.S.

Coeducational: for boys and girls together

Utopian: organized around core principles believed to achieve peace and harmony

Unorthodox: unusual

Curriculum: a course of study

Petitions: documents protesting a certain policy, signed by citizens

Questions:

Do you think it was an easy decision for Ann Maria Jackson to make to seek freedom with all of her remaining children? What dangers did the family face? Why might it be more difficult for them to remain safe while seeking freedom in comparison to an individual adult?

What actions did some young Rhode Islanders take to help their parents aid freedom seekers? What risks were they taking in doing so?

It took incredible courage for enslaved children and adults to seek freedom. It also took courage for free children and adults to help those seeking freedom. Where do you see people in our world today showing courage to escape or change their and their family’s situation or showing courage in helping others? What risks do they each face? Where have you shown courage in your life?

- 1John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 64

- 2William Still, The Underground Rail Road A Record (Philadelphia: Peoples Publishing Company, 1871), 512-514

- 3William F. Davis, Saint Indefatigable: A Sketch of the Life of Amarancy Paine Sarle (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1883), 40

- 4Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R. I.: E. L. Freeman, 1891), 35-38

- 5

- 6Federal Census, New London, Ct., 1850; Federal Census, Kingston, R.I., 1860; Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York: New York University Press, 2019), chapter 1

- 7Federal Census, Westerly, R.I., 1860

- 8Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman, “From Generation to Generation,” Atlantic 64 (August 1889):167-68)

- 9Wyman, “From Generation to Generation”; Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman and Arthur Crawford Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Her Environment (Boston: W.B. Clarke Co., 1914), 1:215-16; Elizabeth C. Stevens, “Mothering as a Subversive Activity in Nineteenth-Century Rhode Island,” Quaker History 84 (Spring 1995): 37-57

- 10Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2008), 1:187

- 11Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport, R.I.: Newport’s Black Museum, 1932), 30

- 12Elizabeth C. Stevens, “A Symmetrical, Harmonious Substantial Character”: Schools for Abolitionist Children in Nineteenth-Century New England,” Schooldays in New England, 1650-1900, The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, June 19-21, 2015, 59-72

- 13The “colored citizens of Providence” to the Honorable General Assembly of the State of R.I. (Petition to Urge the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, February 1851, R.I. State Archives

- 14“The colored citizens of Newport” to the Honorable General Assembly of the State of R.I. (Petition to Urge the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, February 1851, R.I. State Archives)

- 15“Old Pidge House Revealed as Fugitive Slave Hideout,” Pawtucket Times, December 3, 1934, second section; Betty Johnson and James Wheaton, “Pawtucket played role in Underground Railroad,” Pawtucket Times, October 10, 1998; “Old Landmark in Path of Progress, Pawtucket Evening Times, April 11, 1906

- 16“Jacob Babcock’s house on High Street in Ashaway was a stop on the Underground Railroad” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Cynthia Drummond, “A gateway to freedom: Hopkinton provided an important stop on the Underground Railroad,” The Westerly Sun, January 21, 2019 [link]

- 17Ashaway was close to the Connecticut state line, and by “first station” in Rhode Island, Cundall probably meant the first stop for freedom seekers coming from eastern Connecticut. Freedom seekers also came into the state via Westerly, and, in northern R.I., from Fall River and New Bedford to Pawtucket, Central Falls and elsewhere

- 18“Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Russell J. De Simone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad,” Accessed May 16, 2021 [link]

- 19Weeden H. Berry was the sheriff of Westerly for a number of years. John Livingston, Official Directory and Law Register for the United States, for the Year 1866 (New York: C.A. Alvord, 1866), 496

- 20The house of “Preacher John Wilbour” near Hopkinton was probably that of noted Quaker leader John Wilbur who had died in 1856. Accessed May 16, 2021 [link]

- 21“Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Journal, Jan. 13, 1918; Russell J. De Simone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad,” Accessed May 16, 2021 [link]

- 22Margery Gomez O’Toole, If Jane Should Want to Be Sold: Stores of Enslavement, Indenture and Freedom in Little Compton, Rhode Island (Little Compton, R.I.: Little Compton Historical Society, 2016), 221, 256