Immigration to Rhode Island

Essay by Evelyn Sterne, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Rhode Island

In 1793, British immigrant Samuel Slater built the nation’s first mechanized textile mill in Pawtucket and sparked the American Industrial Revolution. The Providence area became the nation’s first manufacturing center, and in the 1840s, it was a magnet for immigrants fleeing the Irish Famine. Over time, Providence also became a center for the production of jewelry, metals, and machinery, and its factories attracted immigrants from French Canada, Italy, Portugal, and other parts of the world. In the late twentieth century, new waves of immigration from the Caribbean, Central America, China and Southeast Asia enriched the diverse tapestry that is Rhode Island.

The Irish were fleeing terrible economic distress. By the 1840s the country’s farmers had become reliant on the potato, which was easy to grow and provided a cheap source of nutrition. When a disease called the potato blight wiped out the crop in 1845, widespread poverty and starvation resulted. Hundreds of thousands of men and women left Ireland for the U.S., despite requiring a journey so difficult the vessels on which they sailed became known as “coffin ships.”

Irish immigrants scattered around Rhode Island’s urban and industrial areas and initially had trouble finding good jobs. Many arrived in poor health or with skills better suited to a farming economy, and they faced prejudice from employers who issued “help wanted” advertisements with the phrase, “no Irish need apply.” Women tended to work as domestic servants and men as unskilled laborers, digging the Blackstone Canal, building Newport’s Fort Adams, or laying railroad lines between Providence and Boston. Entire families found work in the textile mills. Irish neighborhoods were known as “Little Dublins” or “Paddy Towns,” tightly-knit but troubled neighborhoods plagued by poverty-related problems such as crime, alcoholism, and disease.1Evelyn Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 37-38.

Touro Synagogue

Read about Sephardic Jews immigrating to Rhode Island here

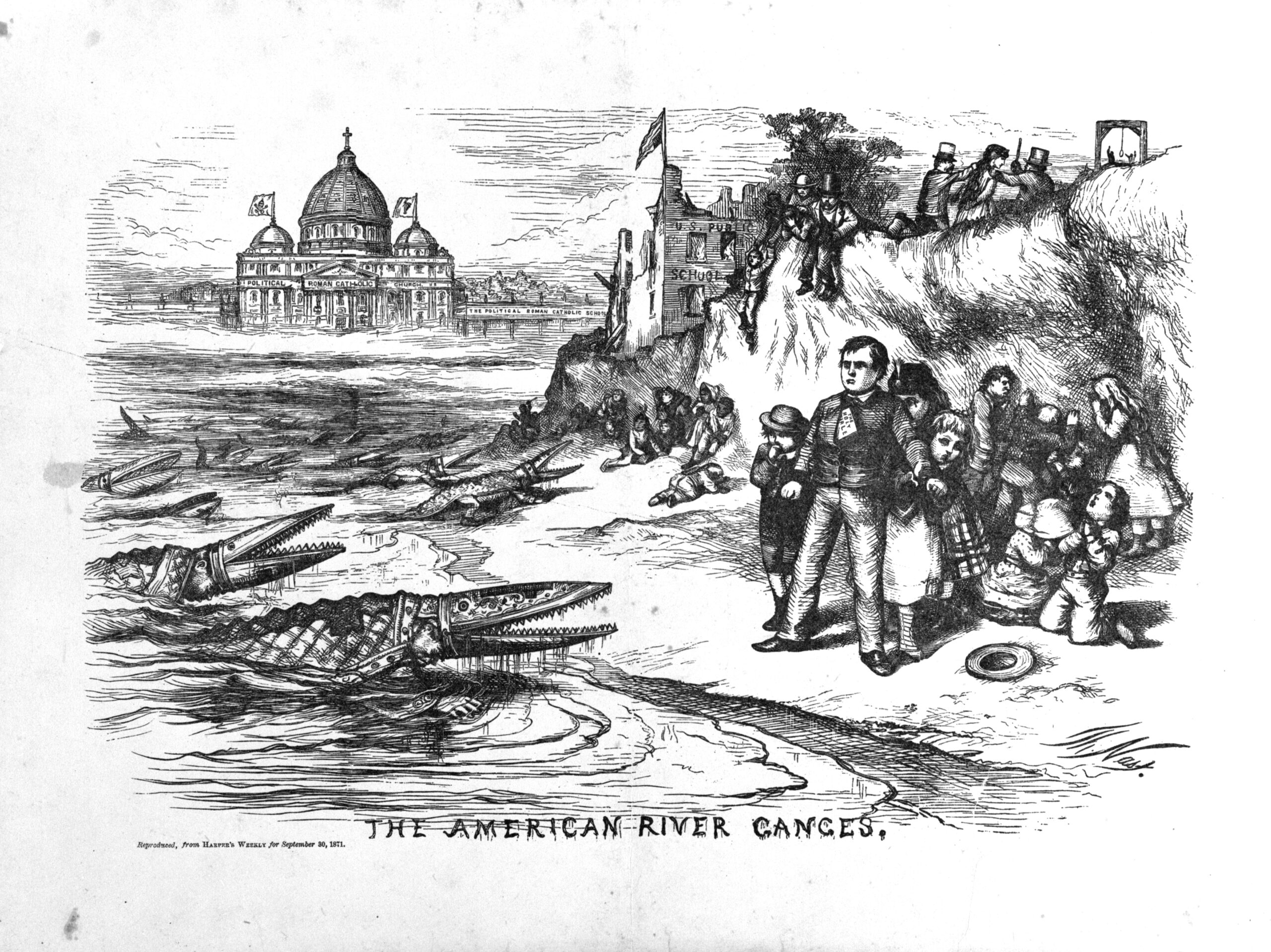

One problem the Irish (as well as later immigrants from other Catholic countries) faced was discrimination on the basis of their faith. Although Rhode Island had been founded on the principle of religious freedom, its Protestants were very concerned about the growing population of Catholic immigrants. By the turn of the twentieth century, more than 50 percent of residents were Catholic.2Sterne, 3. Many Protestants thought Catholicism was an undemocratic religion in which a hierarchy of priests and bishops told parishioners what to believe and how to worship. They even worried the pope was telling American Catholics how to vote and manipulating them in a sinister plot to take over the U.S. government. As a result, Rhode Island was the only state that placed special restrictions on immigrant voters. After the Dorr Rebellion (1841-42), men born in Rhode Island could vote without needing to own property. Immigrants, however, still had to own land in order to vote until 1888 (Native American Indians not included).3To learn more about the Dorr Rebellion, see our Encompass source [link]; Sterne, 24-26, 28-35, 69

Another tragic example of prejudice against Irish Catholics came in 1844 when a young immigrant named John Gordon was convicted on the basis of circumstantial evidence and hanged for the murder of industrialist Amasa Sprague. The case was so controversial, and the evidence against Gordon so weak that it led the state to abolish the death penalty eight years later.4Patrick T. Conley, The Irish in Rhode Island: A Historical Appreciation (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1986), 14.

Ethnic prejudice and voting restrictions made it harder for the Irish to move up the social ladder, but over time many achieved upward mobility. As newer immigrants arrived and took over the less appealing jobs, many Irish factory workers joined labor unions and moved into skilled positions, while others became building tradesmen, streetcar drivers, police officers or firefighters, nurses, or teachers. A small Irish elite included politician Patrick J. McCarthy (who became Providence’s first foreign-born mayor in 1907) and industrialist Joseph Banigan, the state’s first Irish Catholic millionaire.

By the 1860s, a new wave of immigrants was emigrating south from French Canada. A series of crop failures combined with overpopulation had created an economic crisis in Quebec, where families might have as many as sixteen to twenty children.5Albert K. Aubin, The French in Rhode Island: A Brief History (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1988), 13. Many French Canadians needing work looked to the textile mills in Providence and the Blackstone and Pawtuxet river valleys, and they traveled south using the new rail system. They settled in “little Canadas” in Providence’s Olneyville and West End neighborhoods, in Central Falls and Pawtucket, or further north in Woonsocket. Typically fathers and unmarried children worked in the mills while mothers took in sewing and boarders. Mill work was monotonous and exhausting, and living conditions were no better. Many immigrants tolerated the poor conditions as they hoped to save money and return to Canada, which was a short train trip away. For many, the hope of returning home and the commitment to la survivance (the movement to preserve their native language, religion, and culture) initially discouraged them from learning English and becoming U.S. citizens. Over time, however, they became active in American politics and were proud when Aram Pothier became the state’s first French-Canadian governor in 1908.6Sterne, 43-46.

The Wedding Cake House

Read about the Tirocchi Sisters' success in American here

The Irish and French Canadians, as well as Rhode Island’s much smaller population of Germans and Scandinavians, formed part of a national wave of immigrants who arrived between the 1820s and 1880s. Although many encountered discrimination because they were poor or Catholic, they still fit into American society fairly well because they had fair skin, were Christian (except for the German Jews), and came from cultures with which many Americans were familiar. They also arrived at a time when there was ample land and economic opportunity and when the nation was expanding rapidly and needed settlers.

Around 1890, a new and much larger wave of newcomers started to arrive. These immigrants were primarily from Eastern and Southern Europe, with substantial numbers from Mexico and Asia, too. In Rhode Island, this wave brought Portuguese (from mainland Portugal as well as Cape Verde and the Azores), Eastern European Jews, Poles, Greeks, Armenians, and most of all southern Italians. The new immigrants had a much harder time than earlier immigrants. Both native-born Americans and older immigrant groups looked down on them because they tended to have darker skin and came from less familiar cultures. They also arrived at a time when there was less available land because the country already had achieved its “Manifest Destiny” of settling coast to coast, and the jobs available were less attractive. As the nation entered the peak of its industrial age, many skilled jobs were downgraded to unskilled factory positions that required long hours in unsafe conditions for low wages and little job security.

The Rhode Island House of Representatives

Read about how immigrants gained voting rights here

During this period, the largest number of immigrants to Rhode Island came from southern Italy. Political changes after Italy became a unified nation in 1871 had not benefited southern peasants, and overpopulation and an agricultural depression made it harder for farmers to earn a living. Many Italians decided to seek their fortunes in the U.S.. The Italians who reached Providence tended to settle in the North End and on Federal Hill. Outside the capital city, they settled in the Pawtuxet Valley and in Westerly, where many labored in granite quarries. Many Italians found jobs in construction, textile mills, or jewelry factories. Skilled workers labored as tailors, mechanics, stonecutters, or bakers, and others ran barbershops, butcheries, or grocery stores. Wives took in boarders or helped run family businesses, and unmarried women labored in garment factories and millinery shops.7Sterne, 48-49.

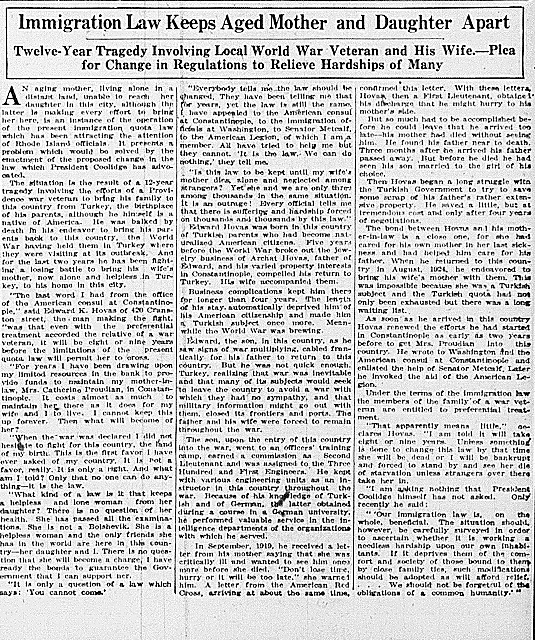

Like the French Canadians, many Italians were slow to put down roots by learning English and becoming citizens as many hoped to save enough money to return home and buy a farm. By the early twentieth century, steamship travel had become so much cheaper and safer that many Italians were what historians call “birds of passage” who traveled back and forth across the Atlantic, working in American factories during the winter and on Italian farms in the summer. This changed after the U.S. enacted a harsh immigration restriction law in 1924; however, Italians who lived in Rhode Island committed to staying. They became increasingly active in politics, switching from the Republican to the Democratic Party by the 1930s and in labor organizing (particularly in the building trades unions). It was a great victory for the community when John Pastore, whose father had immigrated in 1899, became the first Italian-American in the nation to serve as governor (in 1944) and U.S. Senator (in 1950).8Sterne, 51; and Carmela E. Santoro, The Italians in Rhode Island: The Age of Exploration to the Present, 1524-1989 (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1990), 33-35.

At the same time, a smaller but substantial wave of Portuguese immigrants was arriving. The Portuguese were not new to the state. Before the Civil War, a number of Azoreans and Cape Verdeans who had arrived on whaling ships stayed on after the whaling industry declined to work in the Providence and New Bedford textile mills or became farmers in Portsmouth or Little Compton. After 1870, a much larger population (primarily from the Azores) arrived to work in the textile mills and settled in and around Providence (forming distinctive neighborhoods in areas such as Fox Point) and the East Bay. They were motivated both by the promise of better jobs in the U.S. and by the political disruption caused by the founding of the Portuguese Republic in 1910.9M. Rachel Sousa Baxter, Susan A. Pacheco and Beth Pereira Wolfson. The Portuguese in Rhode Island: A History. Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1985), 7-10.

The Catholic Church played a significant role for the Portuguese and other early waves of immigrants. Not all immigrants were devout Catholics when they arrived, but many became more involved with the church because it played a central role in their communities. In the early twentieth century, parishes provided places of worship, offered charity, and educated children in parochial schools. They also built extensive community centers with facilities such as libraries, gyms, and bowling alleys. People went to church not only to worship but also to meet friends, play sports, see movies, join study groups, discuss politics, and join clubs for people of all ages. Parishes also offered useful services such as daycare, English lessons, and help finding jobs. Catholics used their parish societies to organize elaborate religious festivals, such as the Portuguese feast of the Holy Ghost or the Italian feast of the Madonna of Mount Carmel, that celebrated their ethnic heritage and united their communities. For many immigrants, the church became the center of the neighborhood and helped them adjust to American life.10Sterne, Chap. 4.

Providence Journal Article

Read more about the 1924 Immigration Act here

By 1910, two-thirds of the state’s population was made up of immigrants or their children. After 1910 those percentages steadily dropped because of the disruptions of the world wars and the Great Depression and because of the 1924 Immigration Act, which limited the number of people who could enter the nation every year and discriminated against the countries where the newer immigrants came from. The New England textile industry also started to decline in the 1920s as many mills moved to the South, where labor costs were cheaper. Therefore, the region became less attractive to newcomers seeking jobs. In 1965 a new federal law raised the annual limit on immigration and ushered in a new wave of immigration that was dominated nationwide by Latinos and Asians, who were seeking economic opportunity and fleeing the political disruptions of civil wars and the Cold War.

Cape Verdean Sailor

Read more about Cape Verdean immigration to Rhode Island here

Immigration is as important to Rhode Island’s present as it was to its past. Today, more than one in eight Rhode Islanders (or 13.5 percent of the population) is an immigrant, while more than one in seven residents has at least one immigrant parent. The top countries of origin for the state’s newcomers today are, in order from highest to lowest, the Dominican Republic, Portugal, Guatemala, Cape Verde, and China.11American Immigration Council. “Fact Sheet: Immigrants in Rhode Island, October 16, 2017″ [link] Providence has a larger Dominican population as a percentage of the population than any other city in the country. Although its Cambodian community is much smaller, it is also home to one of the largest Cambodian populations as a percentage of the population nationally. Spanish is the most popular language in the homes of Rhode Island immigrants, but dozens of other languages ranging from Portuguese and Italian to Khmer, Chinese, and Hindi, are spoken. The vast majority of the state’s immigrants live in Providence, Central Falls, and Pawtucket.12Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz and Alexandra Filindra, “Immigrants and Immigration in the Ocean State: History, Demography, Public Opinion and Policy Responses” (University of Rhode Island’s Urban Initiative, 2014), 7. Whereas earlier immigrants tended to work in factories, recent immigrants are more likely to work in service industries or technology jobs.

Like earlier waves of immigrants, the state’s Latinos are making political headway as their numbers grow. They have achieved a number of political “firsts,” such as electing Angel Taveras (whose parents immigrated from the Dominican Republic) as Providence’s first Latino mayor in 2011. The much smaller Asian community has long-serving Cranston mayor Allan Fung (the son of immigrants from Hong Kong) as its standard-bearer. Earlier waves of immigrants depended heavily on churches and self-help societies to help them adjust to American life. Recent immigrants have access to a number of government services and benefits, as well as community organizations such as Progresso Latino and the Center for Southeast Asians, which provide educational and social services.13Pearson-Merkowitz and Filindra, 23. They also live in a society where more people have learned to value diversity and multiculturalism. Yet undocumented immigrants (an estimated 2.8 percent of the state’s population) live in a state of uncertainty as politicians debate whether they may enjoy access to the same services as legal residents or even remain in the country.14Pearson-Merkowitz and Filindra, 16.

Terms:

Circumstantial Evidence – indirect evidence-based reasoning to prove a fact that may have more than one explanation or could lead to more than one conclusion

Elite – people deemed superior to others in a society

Manifest Destiny – the belief during the 19th century that it was inevitable and justifiable for the United States to expand throughout the American continent

- 1Evelyn Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 37-38.

- 2Sterne, 3.

- 3To learn more about the Dorr Rebellion, see our Encompass source [link]; Sterne, 24-26, 28-35, 69

- 4Patrick T. Conley, The Irish in Rhode Island: A Historical Appreciation (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1986), 14.

- 5Albert K. Aubin, The French in Rhode Island: A Brief History (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1988), 13.

- 6Sterne, 43-46.

- 7Sterne, 48-49.

- 8Sterne, 51; and Carmela E. Santoro, The Italians in Rhode Island: The Age of Exploration to the Present, 1524-1989 (Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1990), 33-35.

- 9M. Rachel Sousa Baxter, Susan A. Pacheco and Beth Pereira Wolfson. The Portuguese in Rhode Island: A History. Rhode Island Ethnic Heritage Pamphlet Series. Providence: Rhode Island Heritage Commission and Rhode Island Publications Society, 1985), 7-10.

- 10Sterne, Chap. 4.

- 11American Immigration Council. “Fact Sheet: Immigrants in Rhode Island, October 16, 2017″ [link]

- 12Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz and Alexandra Filindra, “Immigrants and Immigration in the Ocean State: History, Demography, Public Opinion and Policy Responses” (University of Rhode Island’s Urban Initiative, 2014), 7.

- 13Pearson-Merkowitz and Filindra, 23.

- 14Pearson-Merkowitz and Filindra, 16.