Cape Verdean Sailor

Nho Mocho Brito, a Cape Verdean seamen, works aboard the famous packet trade schooner, the Ernestina. The Ernestina can be seen to this day in the harbor of the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park.

From Port to Port: The Cape Verdean Connection

Essay by Miguel Youngs, Public Services Assistant, The Rhode Island Historical Society

As of the 2010 census, every single one of the ten largest Cape Verdean communities in the United States is located in either Massachusetts or Rhode Island. This includes the Rhode Island cities of Providence, Pawtucket, East Providence, and Central Falls.1data.census.gov, accessed April 2, 2020 [link] This may seem surprising, but if we understand the history and culture of the Cape Verdean islands and its people, the reasons for this connection become clear.

In 1460, Portuguese ships first pressed into the soft sands of the uninhabited Cape Verdean archipelago. The Cape Verde archipelago consists of ten islands and five islets. As was the common practice of European expansionism, the Portuguese empire immediately claimed ownership of the islands and quickly began to utilize their strategic location off of the Western Coast of Africa as a port along trading routes.2Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 3- 4

Because of the Portuguese participation in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, many Africans were brought to Cape Verde from their respected African countries. The once uninhabited archipelago soon became a bustling epicenter of the maritime industry and the mixing of the multitude of cultures and races that passed through its ports was beginning to shape a singular “Cape Verdean identity.”3Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 1-3 A result of this was the creation of a Portuguese creole language specific to the islands known as Crioulo.

The Portuguese Empire continued to maintain the strongest hold on the islands and a class distinction developed between Cape Verdeans and peoples from the other Portuguese colonies in Africa. Due to cultural and physical similarities, Cape Verdeans were considered “more Portuguese” and were able to enter the civil service and administrative corps in Africa.4Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 5 This combination of status and environment led to a strong relationship with the seafaring industry concentrated in the islands. As colonial exploration pushed westward, trade routes began to broaden, and the connections between the ports of Cape Verde and the ports of Southern New England were born.

Due to a growing population and limited resources on the islands, poverty became widespread in Cape Verde during the mid to late 19th century. Thus, Cape Verdeans, along with millions of other immigrants, began pouring into America in search of economic opportunities. The smallest of the inhabited islands, Brava, holds a particular significance as the overwhelming majority of Cape Verdean immigrants came from there. In fact, early Cape Verdeans in America were often referred to as “Bravas.”5Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 4-5

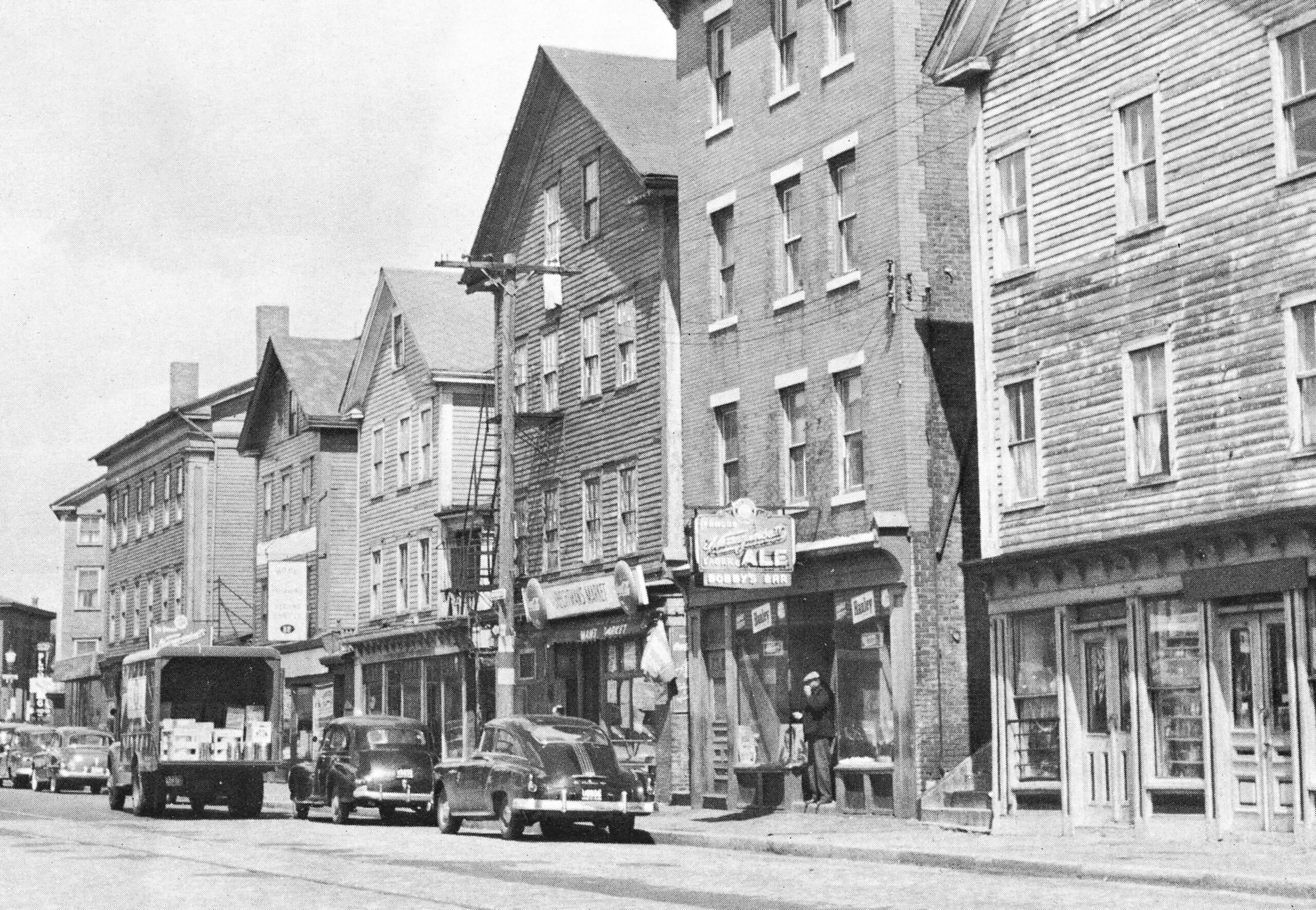

Because of the relationship that had been developed between Brava seamen from the deep-sea fishing and whaling industry and the ports of Southern New England, many of them were compelled to settle in this region in search of more sustainable work. The first Cape Verdean immigrants established settlements in New Bedford, Fall River, Dorchester and Cape Cod in Massachusetts and in Providence, East Providence, Pawtucket, and Newport in Rhode Island.6Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 5-6 In Providence specifically, the Cape Verdean community was heavily concentrated in the Fox Point neighborhood. The history of this community can serve as a microcosm for the complicated relationship Providence had and would continue to have with the various minority communities that call the city home.

The story of Fox Point and the Cape Verdean community begins much in the same way that most immigrant stories from that time begin. People migrated to places that offered jobs. Given Rhode Island’s status as a center of industry (especially the maritime industry), seeing Cape Verdean seamen working on the docks of Providence became a common sight. Work on the dock was strenuous, dangerous, and in many ways undesirable. However, like any job that fits that description, they are reserved for people considered to be at the bottom tier of society. Of course, as immigrants and people of color, Cape Verdeans were very much considered to be on this bottom tier.7Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 7-8

Advancements in technology created a large shift in the types of employment available in America. An example of this is the advent of factory work and steamboats. Both of these had a major impact on Providence’s Cape Verdean community. Steamboats caused old vessels used in the whaling trade to become obsolete and available for repurposing. Cape Verdean dock workers used their built-up resources and seafaring knowledge to acquire these vessels and use them to enter the packet trade which carried goods, mail, and travelers back and forth from West Africa to America. The invention of factories for industrial production increased the opportunities for women and children to work in America. Wives and children could now join Cape Verdean men who, up to this point, had been the only ones able to work in America, and thus, families could be reunited, and a community could be built.8Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 6-7 Inexpensive rent in the Fox Point neighborhood, as well as its close proximity to the port of Providence, made it the perfect place for this community to develop. Clearly, Cape Verdeans in Providence were following the trajectory of resilience and perseverance that has come to define generations of immigrants in America.

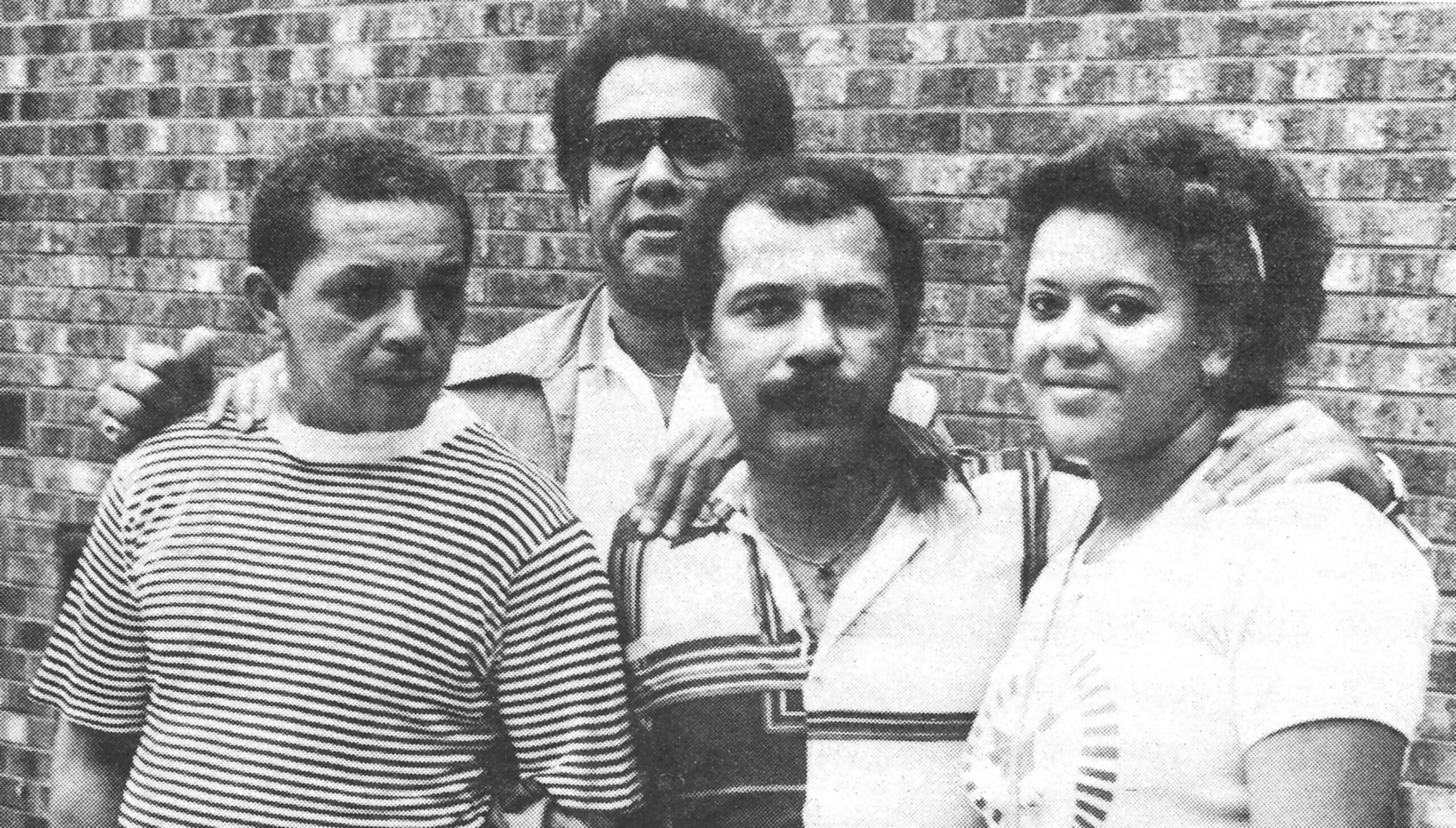

As time continued to pass and the 1800s became the 1900s, Fox Point had become all but synonymous with Cape Verdeans. Living conditions were far from ideal, with many houses lacking indoor bathrooms and racial prejudice still being very much a part of the American experience. Despite this, a strong and vibrant community developed.9Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 14-17 In fact, one can argue that because of all the hardship Cape Verdeans had faced and continued to face, this strengthened their unity as a people and gave the neighborhood the feel as if it were truly just one big family. Everyone looked out for each other, and it was with this spirit that two Cape Verdean men named Manuel Q. Ledo and John F. Lopez started the R.I. International Longshoremen’s Association Local 1329 in 1933. Also known as the Longshoreman’s Union, this was a union designed to strengthen and protect the rights of the dockworkers at the port. This was a monumental achievement not only for Cape Verdeans but for the entire immigrant community whose very existence in the city of Providence manifested from a willingness to work.10Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 25

Despite generational progress, the relationship between Cape Verdeans and the neighborhood of Fox Point would be subjected to forces beyond any of their control. From a real estate perspective, the Fox Point neighborhood, which stretches from Power Street to the harbor, and from the Providence River to the Seekonk River, was valuable land. With notable streets such as South Main Street, Wickendon Street, Hope Street, and Benefit Street, Fox Point was (and still is) a very desirable and convenient place to live. City prospectors were well aware of this and, starting in 1935, plans were being made for an “urban redevelopment” of the area. The Work Progress Administration (WPA), a government program designed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to help lift the American economy out of the Great Depression, sponsored a project called the “Proposed Slum Clearance and Housing Project for Providence.” Effectively classifying the Fox Point neighborhood as a slum, this project would set a standard for future projects and plans for the urban renewal of the Fox Point neighborhood throughout the 1900s.11Sam Beck, “Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement,” Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement: A Public Forum, 1981, 1981), 1-5

Cape Verdeans in Fox Point, and communities like them around the country, are no strangers to the devastating effects urban renewal, redevelopment, and gentrification can have on the culture of a neighborhood. For Fox Point, these terms came in the form of an historic preservationist movement and the expansion of Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).12Sam Beck, “Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement”, Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement: A Public Forum, 1981, 1981), 3-4 When a house is registered as “historic,” its value goes up dramatically. This historical designation is marked by a plaque on the front of the house, a familiar sight to anyone who has walked through modern-day Fox Point. For many former and current residents, there is a love/hate relationship with these plaques. Certainly, there is importance in denoting and preserving the historical status of a house and neighborhood. However, it turned out that the more homes were deemed worthy of plaques, the higher the cost became to live there, and the more poor and minority people had to leave because they could no longer afford to live there.13Mary McKinney, “The Problem with Plaques,” in Fox Point and Its People: a Community Diary (Providence, RI: Fox Point Community Organization, 1979), 17

This can be a difficult concept to approach as it causes a reevaluation of how we view progress. The expansion of universities and an increased focus on historical preservation are arguably “good things” for the city of Providence. Increasing property value in Fox Point has directly led to increased revenue for the city, and the same can be said about the transformation of South Main Street and Wickendon Street into popular shopping and retail sites. What we must then ask ourselves is at what expense are we willing to achieve these goals of “progress”? And in this context, when we use the word “progress,” do we really mean progress for all? The displaced Cape Verdean community would certainly offer a different perspective to these questions. It was their perspective that was not taken into consideration when these changes to their neighborhood began. The history of the Cape Verdean immigrants and their descendants in Rhode Island is just as valid, and preserving it is just as necessary as it is for any other people who have called this state home.

Remnants of the Cape Verdean and Portuguese community still exist in Fox Point. The bakeries, markets, and churches still in use today serve as reminders of the cultural history of the neighborhood. There are approximately 500,00 Cape Verdeans currently living in the United States.14“Cape Verde Population 2020,” Cape Verde Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs), accessed April 2, 2020 [link] These Cape Verdeans represent the unique lineage of one of the largest “voluntary” migrations of Africans to the United States.

Terms:

Archipelago – a term used to describe a group of islands clustered together (other examples include Japan, Hawaii, and the Bahamas)

Trans-Atlanatic Slave Trade – the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas.

Crioulo – a combination of Portuguese and native languages that is spoken by Cape Verdeans

Packet Trade – the transportation of goods, mail, and passengers between West Africa and America

Gentrification – the process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste

Historic Preservation – a movement that seeks to preserve, converse, and protect buildings, objects, landscapes, and other artifacts of historical significance.

Questions:

What are some of the things that make Cape Verdean immigrants unique?

What effects did putting historical plaques on the houses of Fox Point have? Why do some people like and others dislike the plaques?

Is gentrification a bad thing? Why do you think it is or isn’t?

What are things that the city of Providence can do to ensure that disadvantaged communities are not forced out of neighborhoods they have long called home by stronger and more influential classes and institutions?

- 1data.census.gov, accessed April 2, 2020 [link]

- 2Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 3- 4

- 3Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 1-3

- 4Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 5

- 5Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 4-5

- 6Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 5-6

- 7Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 7-8

- 8Sam Beck, From Cape Verde to Providence: the International Longshoremen’s Association(Local 1329. Providence, RI: Local 1329, 1983), 6-7

- 9Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 14-17

- 10Waltraud Berger. Coli and Richard A. Lobban, The Cape Verdeans in Rhode Island (Providence: Published jointly by the Rhode Island Heritage Commission and the Rhode Island Publication Society, 1990), 25

- 11Sam Beck, “Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement,” Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement: A Public Forum, 1981, 1981), 1-5

- 12Sam Beck, “Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement”, Focus on Fox Point Cape Verdean Displacement: A Public Forum, 1981, 1981), 3-4

- 13Mary McKinney, “The Problem with Plaques,” in Fox Point and Its People: a Community Diary (Providence, RI: Fox Point Community Organization, 1979), 17

- 14“Cape Verde Population 2020,” Cape Verde Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs), accessed April 2, 2020 [link]