The Rhode Island House of Representatives

This photo depicts the Rhode Island House of Representatives at work. In 1888, Democrats and Republicans in the Rhode Island government compromised to reach the proposed state constitutional amendment which would become the Bourn Amendment. The Bourn Amendment expanded voting rights in Rhode Island.

The Bourn Amendment

By Talia Brenner, Brown University Alumna

Before the Bourn Amendment was proposed in 1888, the notion of who gets to vote in Rhode Island came from the voting rights as they were laid out in the 1663 Colonial Charter. Rhode Island was using the charter as a constitution or governing document. Each state has a constitution that resembles the national Constitution but only deals with issues relating to that particular state. State governments are run like the federal government, but on a smaller scale. The elected head of the state is the governor, just as the president is the head of the federal government. Similarly, states have organizations called legislatures, which make laws just as the U.S. Congress does. State legislatures are allowed to create laws that affect their citizens as long as they do not contradict any laws set by the federal government.1“Amending State Constitutions,” Ballotpedia, accessed January 16, 2020, [link]

The Colonial Charter stated that only men who owned a certain amount of property were allowed to vote in Rhode Island. The law said that men who were born in the United States were allowed to vote if they owned $134 worth of property or if they paid a $1 fee when voting. Men who were not born in the United States but who had immigrated here and become citizens were only allowed to vote if they owned $134 worth of real estate, not just any property. The rules did not directly ban all immigrant men or poor men from voting, but they banned a lot of them indirectly. Many immigrant men lived in cities or towns where they rented houses or apartments instead of buying land. Since they did not have the required $134 of real estate, they would not be allowed to vote.2Chilton Williamson, “Rhode Island Suffrage since the Dorr War,” The New England Quarterly 28 no. 1 (1955): 36, [link]

Even for those who were born in the United States and only needed to pay a $1 fee, the law still prevented some men from voting. It is worth remembering that although $1 does not seem like that much money today, in the late 1800s, it was worth as much as about $25 would be worth today. Even if a poor man had enough money, he may have decided that the money would be better spent on necessities such as food or clothing.

The restrictions on who was allowed to vote in Rhode Island had political consequences. Poor men, immigrant men, and men living in cities tended to vote for Democrats, while middle-class or rich men who were not immigrants and lived in rural areas or small towns tended to favor Republicans. This split is partially because the parties tried to pass laws that would help those different groups but also because parties at that time relied on what were called political machines. Machines were organizations that gave out favors, like money or jobs, to people who voted for their politicians. Machines would try to get reliable votes from particular groups of voters. For instance, Democratic machines often tried to get votes from Irish immigrants living in cities. Since so many of the men who would vote for Democratic candidates could not or did not vote, the voting restrictions helped Republican politicians in Rhode Island stay in power. The Republican leadership knew that they benefited from voting restrictions and were determined to keep the laws as they were.

Many people were also prejudiced against immigrants and believed stereotypes that immigrants were unintelligent and lazy. These stereotypes caused a lot of non-immigrant Americans to think that immigrants should not vote because they would not make educated decisions about which candidate to vote for. Stereotypes about Catholics were also powerful since so many immigrants at this time were Catholic. Many Americans believed the stereotype that Catholics could not think independently and would vote for whomever their priests told them to vote for. Some Americans even worried that the Catholic Church would start to control the United States if Catholic immigrants were allowed to vote! These fears caused states like Rhode Island to limit voting rights for immigrants.3David H. Bennett, “An Essay from 19th Century U.S. Newspapers Database Immigration and Immigrants: Anti-immigrant Sentiment,” Gale.com, accessed January 16, 2020, [link]

By the late 1880s, though, the situation was changing. Democrats began to fight harder and harder to get rid of the money-based restrictions on who could vote.4John D. Buenker, “The Politics of Resistance: The Rural-Based Yankee Republican Machines of Connecticut and Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly 47 no. 2 (1974): 222 [link] Growing numbers of immigrants got involved with political organizations such as the Equal Rights Association, where they showed their support for changing the voting laws.5Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 68.

Republican politicians realized that “the change must come sooner or later,” and that it should just happen already, “like the pulling of a tooth.”6“The Bourn Amendment: Possible Effects on Political Parties,” Providence Journal, April 23, 1888, 8.

The Republican governor Augustus O. Bourn proposed an amendment to the state constitution, named the Bourn Amendment, which would change the law to expand voting rights. The Bourn Amendment stated that all male citizens, whether they were born in the United States or had immigrated, could vote if they owned $134 of property (not just real estate property, meaning if they owned enough things that totaled $134, they would qualify to vote). Men who did not meet the property restriction could vote in some elections, but not on financial issues or for city council members.7Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 69.

This proposed amendment was a compromise between what the Republicans wanted, which was not to change the law at all, and what the Democrats wanted, which was to get rid of all the money-based restrictions on voting.8Chilton Williamson, “Rhode Island Suffrage since the Dorr War,” The New England Quarterly 28 no. 1 (1955): 42, [link] Democrats were generally more excited about the proposed amendment than Republicans were, but in general both Republicans and Democrats supported the amendment. There were some Democrats who were angry that the amendment would not make a big enough change but who decided that having this amendment would be better than having no amendment at all.

States in the U.S. each have different ways of amending their constitutions, although the procedures are all similar. In Rhode Island, one of the ways to amend the state constitution is through a referendum, a question about a law that politicians put on a ballot for all the voters across the state to vote on.9Ballotpedia, “Amending State Constitutions.” n.d., [link] The Bourn Amendment passed easily through a referendum. According to the Providence Journal, the final total was 20,068 votes for the amendment and 12,193 votes against it.10“The Bourn Amendment Vote,” Providence Journal, November 17, 1888, 8.

After the amendment passed, there was still some confusion about how voting would actually work with the new law. So, the governor gave the legislation to the judiciary branch, whose role is to interpret the law. The state Supreme Court, which is the highest court in the state just like the U.S. Supreme Court is the highest court in the country, looked over the new law. They created procedures in agreement with the new law, such as steps for registering to vote.11“The Supreme Court Decides that the Present Registry Laws are Operative under the Bourn Amendment,” Providence Journal, November 25, 1888, 4.

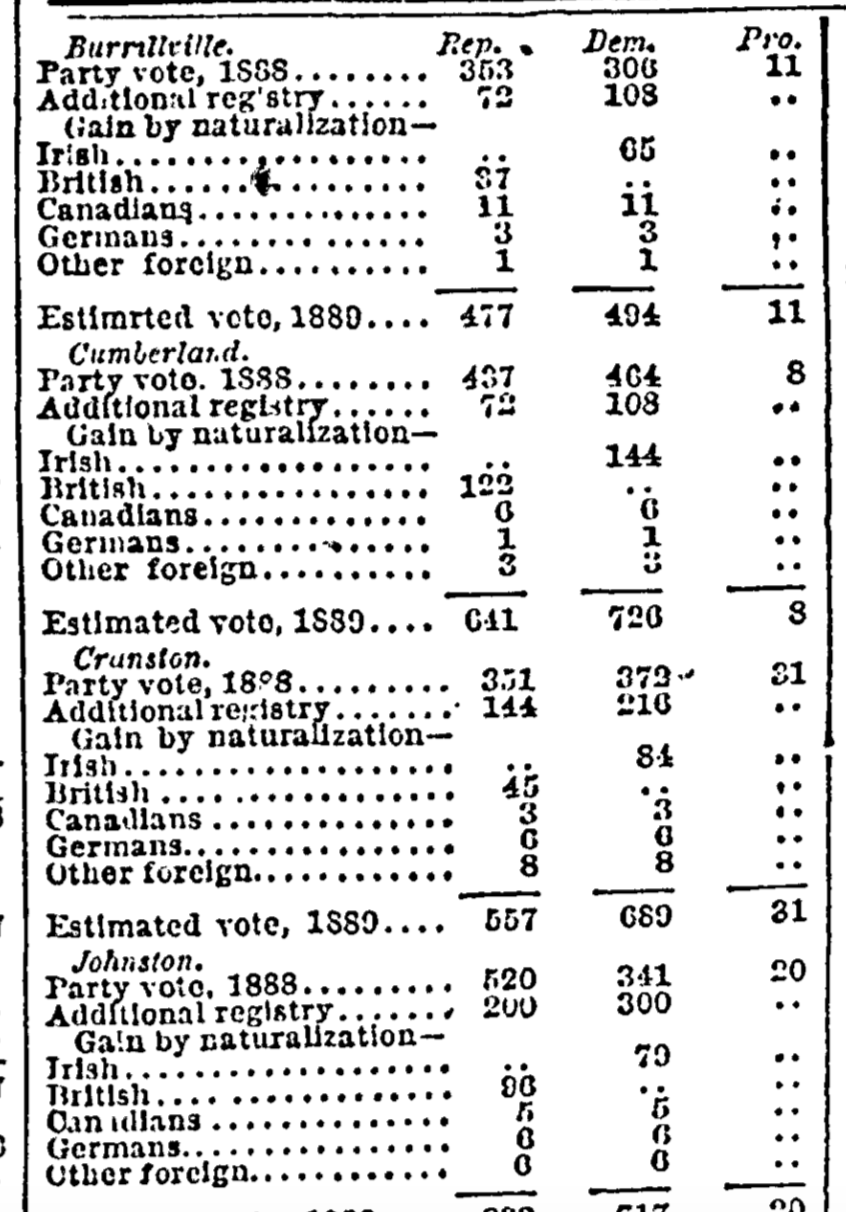

The Bourn Amendment did expand voting rights in Rhode Island. In 1889, 3,411 immigrants were allowed to vote for the first time.12“Extension of Suffrage: Effect of the Bourn Amendment upon Foreign-Born Residents and Aliens in Coming Elections,” Providence Journal, April 6, 1888, 8. Even those who were already legally allowed to vote voted for the first time.13“Registration of Voters,” Providence Journal, December 22, 1889, 8. We can make an educated guess and assume that at least some of these people started voting because they were inspired by the new law.14Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 71.

However, the Bourn Amendment did not change or eliminate all barriers to voting. There was still a $134 property restriction that prevented many poor people, including many immigrants and people of color, from voting in important city elections. The outcomes of these elections affected everyone’s lives greatly, but poorer citizens without voting rights did not have as much of a say in these government matters.

Also, the Bourn Amendment only included men. Women, immigrants, and U.S. citizens were not given any voting rights from the amendment. The Bourn Amendment also did not change the fact that the majority of voters were still White. Black, non-immigrant men living in Rhode Island had been legally allowed to vote even before the Bourn Amendment, but continued to vote in low numbers because of factors such as racist voter intimidation,15For more information on teaching your students about different forms of voter suppression visit Teaching Tolerance [link] which the Bourn Amendment and other laws at the time did not address.16Richard H. Rohrs, “Exercising Their Right: African American Voter Turnout in Antebellum Newport, Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly 84, no. 3 (2011): 418, [link]; “British Americans: Addressed by Speakers of Different Political Faiths,” Providence Journal, March 24, 1889, 10. And in most states, Native Americans did not even gain official voting rights until the 1900s.17National Congress of American Indians, Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction, 32, [link]

We often think of voting rights as something that gets better and more inclusive over time, but the story of the Bourn Amendment reminds us that it doesn’t always work that way. In the many years since the Bourn Amendment, new groups of people have gained the right to vote, but there are groups of people, like people who have been convicted of a crime, whose voting rights are still not guaranteed.18For more information on voting rights today, visit Teaching Tolerance [link]. For teachers: free lesson plan from Teaching Tolerance with a free account [link]

As of January 2020, Rhode Island’s Constitution states, “Every citizen of the United States of the age of eighteen years or over who has had residence and home in this state for thirty days next preceding the time of voting…shall have the right to vote for all offices to be elected and on all questions submitted to the electors…No person who is incarcerated in a correctional facility upon a felony conviction shall be permitted to vote until such person is discharged from the facility.”19“Constitution of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,” State of Rhode Island General Assembly, accessed January 16, 2020 [link]

The Bourn Amendment is a marker in the long history of voting rights in Rhode Island and America that continues today.

Terms:

Federal: the national level of government

Political machines: organizations that gave out favors, like money or jobs, to people who voted for their politicians. At the time of the Bourn Amendment, machines were powerful in many areas of the U.S., especially in cities

Stereotype: a prejudiced belief about a group of people

Questions:

Why do people care so much about voting rights?

Do you think the politicians who supported the Bourn Amendment believed that voting was a right (something that everyone should be allowed to do) or a special privilege? Why?

Did the story of the Bourn Amendment affect the way that you thought about the history of voting rights? How so? If it didn’t, why not?

In 1964, the federal government ruled that charging people a fee to vote is illegal because it indirectly prevents some people from voting. Now, there are other restrictions on voting, like the requirement to have an ID, limited open hours at polling stations, and the fact that Election Day isn’t a national holiday, meaning that some people can’t take time off of work to vote. How do you think these circumstances impact people’s ability or decision to vote?

- 1“Amending State Constitutions,” Ballotpedia, accessed January 16, 2020, [link]

- 2Chilton Williamson, “Rhode Island Suffrage since the Dorr War,” The New England Quarterly 28 no. 1 (1955): 36, [link]

- 3David H. Bennett, “An Essay from 19th Century U.S. Newspapers Database Immigration and Immigrants: Anti-immigrant Sentiment,” Gale.com, accessed January 16, 2020, [link]

- 4John D. Buenker, “The Politics of Resistance: The Rural-Based Yankee Republican Machines of Connecticut and Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly 47 no. 2 (1974): 222 [link]

- 5Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 68.

- 6“The Bourn Amendment: Possible Effects on Political Parties,” Providence Journal, April 23, 1888, 8.

- 7Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 69.

- 8Chilton Williamson, “Rhode Island Suffrage since the Dorr War,” The New England Quarterly 28 no. 1 (1955): 42, [link]

- 9Ballotpedia, “Amending State Constitutions.” n.d., [link]

- 10“The Bourn Amendment Vote,” Providence Journal, November 17, 1888, 8.

- 11“The Supreme Court Decides that the Present Registry Laws are Operative under the Bourn Amendment,” Providence Journal, November 25, 1888, 4.

- 12“Extension of Suffrage: Effect of the Bourn Amendment upon Foreign-Born Residents and Aliens in Coming Elections,” Providence Journal, April 6, 1888, 8.

- 13“Registration of Voters,” Providence Journal, December 22, 1889, 8.

- 14Evelyn Savidge Sterne, Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church In Providence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 71.

- 15For more information on teaching your students about different forms of voter suppression visit Teaching Tolerance [link]

- 16Richard H. Rohrs, “Exercising Their Right: African American Voter Turnout in Antebellum Newport, Rhode Island,” The New England Quarterly 84, no. 3 (2011): 418, [link]; “British Americans: Addressed by Speakers of Different Political Faiths,” Providence Journal, March 24, 1889, 10.

- 17National Congress of American Indians, Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction, 32, [link]

- 18

- 19“Constitution of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,” State of Rhode Island General Assembly, accessed January 16, 2020 [link]