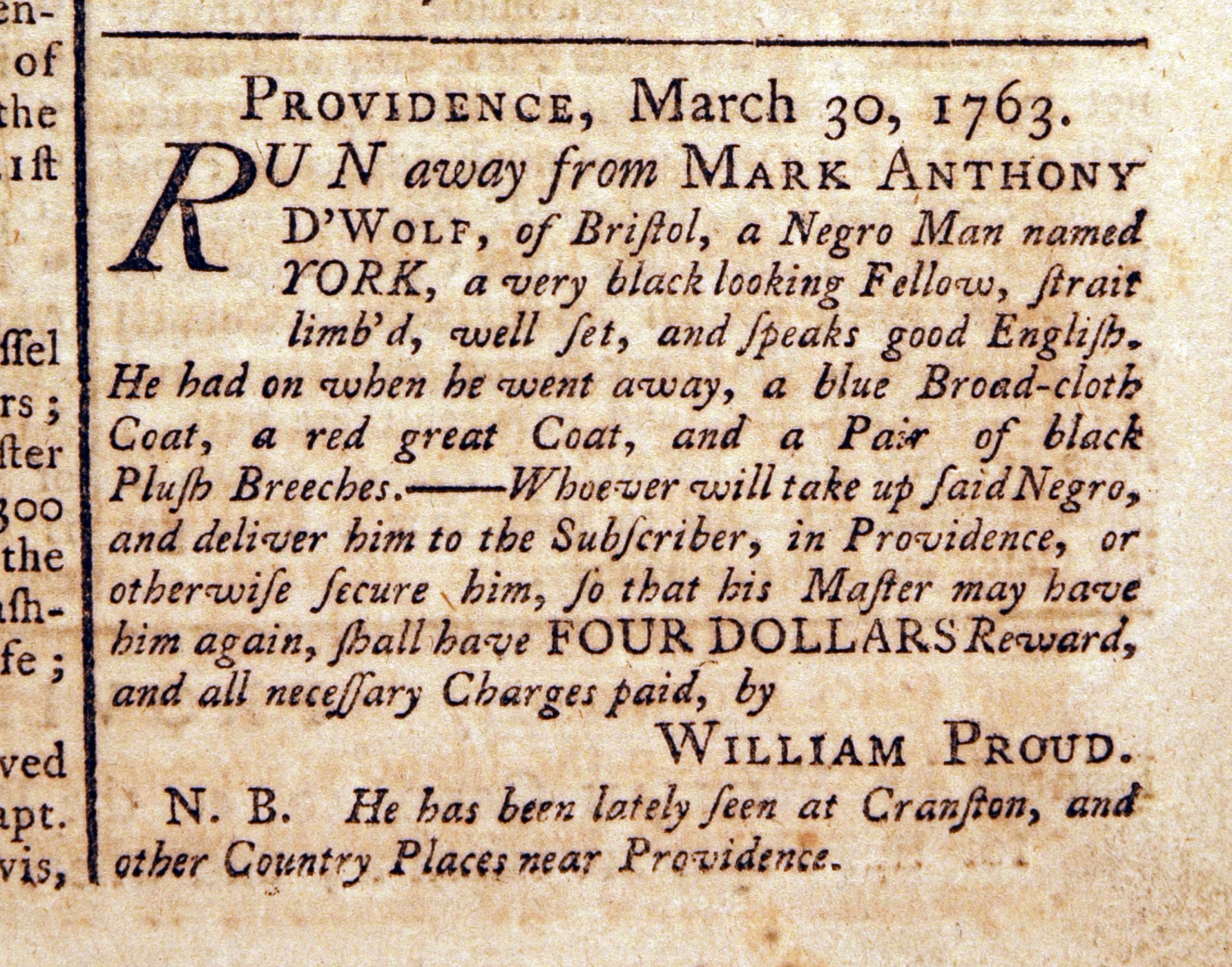

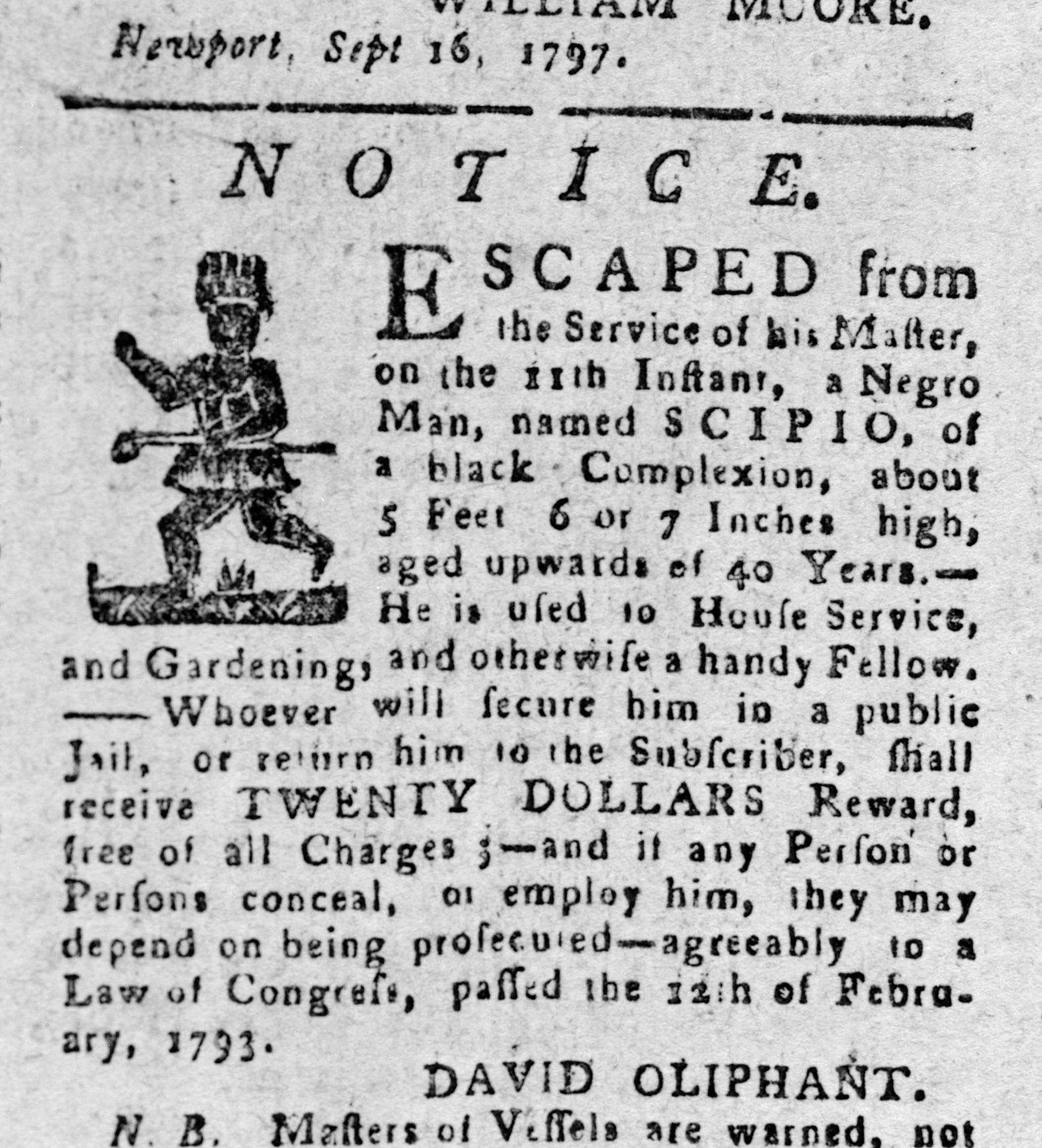

Newspaper Advertisement for “runaway slave”

Between 1732 and 1775, 100 runaway slave advertisements were placed by enslavers in Rhode Island’s local and regional papers. Running away was one form of resistance against enslavement though there was risk of punishment.

Black Civil Rights in Rhode Island Before the 1960s

Essay by Geralyn Ducady, Director of the Newell D. Goff Center for Education & Public Programs

The way African Americans and people of African heritage were treated by White society during the early period of colonialism (~1636-1770s) in this region, and still to this day, stems from a long history of racism that began with chattel slavery and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The first enslaved Africans were brought to the Rhode Island colony sometime before 1650. The Colony of Rhode Island enacted a law that stated no persons could be enslaved for more than ten years in 1652, the first English colony in the Americas to do so, but the law went unenforced or ignored. The first documented slave ship, the Seaflower, brought enslaved Africans through Newport in 1696. Since the beginnings of enslavement in the American colonies, there has been a long history of successes and setbacks for African-descended people in the arena of civil rights. The fight for civil rights began long before the 20th-century Civil Rights Movement.1For more information about the trans-Atlantic slave trade, see the EnCompass module, Rhode Island, Slavery and the Slave Trade [link] and the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice Report [link]2Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:4

From the very early years of Black enslavement by many different countries, those forced into slavery found ways to express their own agency and resistance. Enslaved people were ripped from their families in countries in Africa, endured forced marches and imprisonment on the west coast of Africa, were pressed onto over-crowded, disease-ridden ships whose destinations were unknown to them, and labored without pay or fair treatment to fund the colonial economy. One way the enslaved employed personal agency was to initiate or join insurrections during the Middle Passage.3See the EnCompass essay “Attempts at Freedom: Fighting Back on Rhode Island’s Slave Trading Ships” [link] People banded together to attempt to take over the enslavers’ ship. These acts of resistance rarely saw success but demonstrated that the enslaved did not readily accept their fates.4Elizabeth Donnon. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America. Vol. 1-3. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1930) Before enslaved people even reached the Americas, and because of the well-known atrocities noted above, many enslaved people opted to exert control over their destiny by taking their own lives, usually by jumping overboard during the Middle Passage. Shipbuilders even added netting to the sides of ships to prevent deaths by suicide. To enslavers, the more people lost to death, the less money those who invested in the slave trade would earn. Suicide was a tragic but effective way for enslaved people to defy enslavers and refuse to accept enslavement.5Terri L. Snyder. “Suicide, Slavery, and Memory in North America.” The Journal of American History. Vol. 91 No. 1 (June 2010), pp. 39-62); Terri L. Snyder. The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America. University of Chicago Press. 2015

In the Americas and Rhode Island, enslaved people found further ways to resist. Between 1732 and 1775, 100 runaway slave advertisements were placed in Rhode Island’s local and regional papers.6Christy Mikel Clark-Pujara. Slavery, Emancipation and Black Freedom in Rhode Island, 1652-1842. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Iowa. 2009. P. 85. Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link] Running away came with the risk of severe punishment if caught, or never seeing loved ones again, and never having the sense of feeling settled. The constant worry of being caught, not knowing who to trust, and living in fear of being returned to bondage meant the enslaved never felt truly free. But running away was still a means to gain control over one’s life and defy enslavers and the overarching system of slavery.7Lauren Landi. Reading Between the Lines of Slavery: Examining New England Runaway Ads for Evidence of an Afro-Yankee Culture. Pell Scholars Senior Thesis. Salve Regina University. 2012: p. 4-5. Electronic Document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link] Enslaved people sometimes used waterways to escape. In response, the Rhode Island General Assembly instituted an act in 1714 that forbade enslaved people to board ferries alone without a certificate of ownership from their enslavers. They stowed away, or hid, on ships in Newport, Bristol, and Providence. The General Assembly, in turn, allowed enslavers to search privately owned ships and instituted an act in 1757 that fined ship captains for “stealing” slaves if an enslaved person was found aboard. Some of the escapees demonstrated further resistance against their enslavers by setting fire to barns and even homes.8Christy Clark-Pujara. Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: New York University Press. 2016. P. 54-56

Free Blacks, along with Whites, helped enslaved people run away through what became known as the Underground Railroad, a network of places that helped escaped people hide as they put distance between themselves and their enslavers. This network was present even after Rhode Island outlawed slavery because the practice was still allowed in other states, particularly those in the southern United States, where the question of slavery became increasingly contentious. The Underground Railroad helped escapees move to northern free states and often helped them get as far north as Canada. There were stops along the Underground Railroad throughout Rhode Island, such as Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s home in Central Falls, Jacob Babcock’s home in Westerly, and Isaac Rice’s home in Newport.9American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, Region I, “The Underground Railroad in New England.” Maine Collection. 33. 1976. Electronic document. Accessed November 23, 2020 [link]; Russell DiSimone. “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered.” Small State Big History. February 23, 2019. Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

Another subtle form of resistance was available to the enslaved in the form of dress and hairstyles. Altering the clothing their enslavers gave them, many enslaved people added colorful patches, traded clothing with each other, and dyed clothing to create vibrant colors. They created hairstyles to mock their White owner’s wigs, or they cropped their hair short.10Stephanie Camp, “The Pleasures of Resistance: Enslaved Women and Body Politics in the Plantation South, 1830-1861,” Journal of Southern History 68:3 (2002): 533-572; Lauren Landi. Reading Between the Lines of Slavery: Examining New England Runaway Ads for Evidence of an Afro-Yankee Culture. Pell Scholars Senior Thesis. Salve Regina University. 2012: p. 4-5. Electronic Document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]; David Waldstreicher, “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly 56:2 (1999): 243-272

Some enslaved people were allowed to work side jobs to eventually pay for their freedom, or to self-liberate. Duchess Quamino, for example, became known as the pastry queen of Rhode Island. She gained permission from her enslavers to sell her pastries. She was then able to purchase her freedom in 1780 and, later, that of her children. Her former enslavers continued to allow her to use their kitchen after she purchased her freedom.11Stages of Freedom. “On the Rhode to Freedom.” Electronic Document. Accessed August 3, 2020 [link] In another example of enslaved people expressing agency, every June enslaved Africans in Rhode Island held something called the Negro Elections. 12Joseph P. Reidy. “Negro Election Day’ & Black Community Life in New England, 1750-1860.” Marxist Perspectives 8:3 [Fall, 1978] p. 102-117; Melvin Wade. “Shining in Borrowed Plumage”: Affirmation of Community in the Black Coronation Festivals of New England (c. 1750-c. 1850).” Western Folklore 40:3 (July 1981): 211-231; Shane White, “’It Was a Proud Day’: African Americans, Festivals, and Parades in the North, 1741-1834.” Journal of American History 81:1 (June 1994): pp. 13-50 This festive gathering was a way for the enslaved people to see their friends, families, and other loved ones, hear and share news, and maintain connections to traditional cultures through food, religious practices, dancing, and story-telling. An enslaved man would be “elected” to act as an honorary governor or king during the festivities. The festivities associated with the Elections were a way for enslaved people to express their humanity even though someone legally owned them. Originally organized by enslavers as a way to show off their enslaved people to each other, enslaved people appropriated the day for themselves.13Christy Clark-Pujara. Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: New York University Press. 2016. P. 56-59

As enslaved Africans gained their freedom from enslavement through manumission, self-liberation, or through the Gradual Emancipation Act, the Black populations in Rhode Island became a mix of free and enslaved. Although many enslaved Africans had learned skilled trades working alongside their enslavers who were craftsmen or working as craftsmen themselves in their enslaver’s shops, those who became free often had a difficult time finding and sustaining well-compensated work. Many employers refused to hire Black employees because of racial prejudice. Even when Rhode Island’s Gradual Emancipation Act went into effect, the increasing free Black population continued to have difficulty finding work. The lack of work led to poverty, and poverty resulted in a lack of access to decent housing, medical care, and other necessities. Benevolent societies such as the Free African Union Society, formed in 1780 in Newport, were established by successful free Black Americans to help those facing poverty. These societies raised funds to help newly free Blacks pay for medical services, supplies, and even burial fees. Some organizations raised funds with the idea of eventually helping people relocate or move to Africa.14Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:5

In addition to benevolent aid societies, Black Rhode Islanders also formed their own churches, schools, businesses, and other groups to support members of their community. The Free African Union Society established one of the first private schools that was organized, supervised, attended, and taught by those of African heritage and it had free tuition.15See the EnCompass essay “Free Black Communities in Rhode Island” for more information [link]

Although Black women were allowed to hold membership in the Free African Union Society, they did not have voting rights within the organization. Demonstrating their commitment to the concept of self-determination, Sarah Lyna and Obour Tanner established their own African Female Benevolent Society in 1809. Lyna taught at the African School. The first public school for African children supported by the city of Providence was established on Meeting Street. The building for the school still stands today and is the home of the Providence Preservation Society.16Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:7

After the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, African Heritage people across the United States participated in Emancipation Day celebrations that were then celebrated annually. Because the news of emancipation reached different areas of the country at different times, the annual celebrations occurred on different dates depending on where one lived at the time the news of freedom arrived. As the tradition continued, some people celebrated on January 1 to commemorate the date the proclamation was issued, while others celebrated on August 1, the date news reached Blacks in the Caribbean. In Rhode Island, Emancipation Day has been celebrated at least as far back as August 1854 in Roger Williams Park and into modern times in places like Crescent Park and Rocky Point Park with swimming, picnicking, riding amusement rides, and a chance for old and young to gather. The celebration continues today as “Juneteenth” celebrations at places like Roger Williams Park and Waterplace Park in downtown Providence. Juneteenth celebrations today occur worldwide and are held on June 19th every year. This date was chosen to represent when Union soldiers of the Civil War in Galveston, Texas learned that the War had ended and that the enslaved people were now free. Texas was the final confederate state to surrender on June 19, 1865. This was two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Scholars debate the reasons why it took so long for Texas to learn about the end of the war, but the date marks when the last of the enslaved people learned that they were free.17The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019:5018Juneteenth.com. “The History of Juneteenth.” Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

Despite discrimination by society, Black men volunteered to fight in wars. During the Revolutionary War, many enslaved Blacks joined the military in order to gain their freedom. Black men also fought in the Civil War against the institution of slavery that was still occurring in the southern United States. After fighting against xenophobia and discrimination overseas during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, Black soldiers returned home to a country that still treated them poorly and with disdain. Black Americans realized more needed to be done on the home front. Though legal enslavement was long over, discrimination, racism, and unequal opportunities remained. It was especially after WWII that Black Americans recognized that the fight for civil rights needed to be elevated. The World Wars brought with them a new era in the struggle for African American civil rights where people of African heritage would fight for fair housing, fair schooling, fair employment, and the right to equity and equality as citizens of this state.19Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:7-8

Terms:

Chattel Slavery: a form of enslavement that was hereditary and never ends. Many cultures had a form of enslavement in their systems that was usually used as payment for a debt or for a crime, and which had an end date and was not hereditary. Slavery in the United States was chattel slavery

Agency: the ability to take actions that may influence or change the course of one’s destiny. In this case, enslaved people trying to change the control or influence enslavers had over them

Insurrection: an uprising. In this case, enslaved people working together to overtake enslavers on a slave ship and take control of the ship itself

Middle Passage: the oceanic journey between West Africa and the Americas for enslaved Africans who were captured to be traded and sold

Self-liberate: to free oneself from a situation. In this case, enslavement

Negro: a term used to describe people of African descent or with dark-colored skin. During the Civil Rights Movement, this word was used often whereas it is now considered disrespectful. However, some people still self-identify with this term. You may also come across the terms African American, Black, person of color, colored person, or colored. Colored person and colored are outdated terms

Appropriated: take something created or made by another person and turn it into something for one’s self

Manumission: when an enslaver released their right of ownership over an enslaved person

Self-determination: taking control over one’s own life, often in the face of oppression or an obstacle

Gradual Emancipation Act: in Rhode Island, rather than giving all enslaved people their freedom at once, this Act to gradually allowed people their freedom based on their age. This benefited the enslavers who wouldn’t lose their free labor all at once

Discrimination: the act of treating a person or group of people differently because of their skin color or other category such as age, sex, or religion

Xenophobia: prejudice against someone from another country

Equity: helping people who have been historically denied access to resources and opportunities

Equality: treating everyone the same and giving people the same access to opportunities or resources

Questions:

In this essay, you read about Emancipation Day celebrations historically and Juneteenth celebrations that have continued on today. Why do you think people prioritized celebrations despite being forced into the horrific conditions of slavery historically and still continue to celebrate despite inequity faced by Black Americans? What do you think those celebrations symbolize? Why are they meaningful?

Can you think of an example of an opportunity that is equal but not equitable? Why might an equitable process or system be necessary to ensure people of all backgrounds can benefit from an opportunity or resource?

- 1

- 2Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:4

- 3See the EnCompass essay “Attempts at Freedom: Fighting Back on Rhode Island’s Slave Trading Ships” [link]

- 4Elizabeth Donnon. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America. Vol. 1-3. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1930)

- 5Terri L. Snyder. “Suicide, Slavery, and Memory in North America.” The Journal of American History. Vol. 91 No. 1 (June 2010), pp. 39-62); Terri L. Snyder. The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America. University of Chicago Press. 2015

- 6Christy Mikel Clark-Pujara. Slavery, Emancipation and Black Freedom in Rhode Island, 1652-1842. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Iowa. 2009. P. 85. Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

- 7Lauren Landi. Reading Between the Lines of Slavery: Examining New England Runaway Ads for Evidence of an Afro-Yankee Culture. Pell Scholars Senior Thesis. Salve Regina University. 2012: p. 4-5. Electronic Document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

- 8Christy Clark-Pujara. Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: New York University Press. 2016. P. 54-56

- 9American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, Region I, “The Underground Railroad in New England.” Maine Collection. 33. 1976. Electronic document. Accessed November 23, 2020 [link]; Russell DiSimone. “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered.” Small State Big History. February 23, 2019. Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

- 10Stephanie Camp, “The Pleasures of Resistance: Enslaved Women and Body Politics in the Plantation South, 1830-1861,” Journal of Southern History 68:3 (2002): 533-572; Lauren Landi. Reading Between the Lines of Slavery: Examining New England Runaway Ads for Evidence of an Afro-Yankee Culture. Pell Scholars Senior Thesis. Salve Regina University. 2012: p. 4-5. Electronic Document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]; David Waldstreicher, “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly 56:2 (1999): 243-272

- 11Stages of Freedom. “On the Rhode to Freedom.” Electronic Document. Accessed August 3, 2020 [link]

- 12Joseph P. Reidy. “Negro Election Day’ & Black Community Life in New England, 1750-1860.” Marxist Perspectives 8:3 [Fall, 1978] p. 102-117; Melvin Wade. “Shining in Borrowed Plumage”: Affirmation of Community in the Black Coronation Festivals of New England (c. 1750-c. 1850).” Western Folklore 40:3 (July 1981): 211-231; Shane White, “’It Was a Proud Day’: African Americans, Festivals, and Parades in the North, 1741-1834.” Journal of American History 81:1 (June 1994): pp. 13-50

- 13Christy Clark-Pujara. Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: New York University Press. 2016. P. 56-59

- 14Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:5

- 15See the EnCompass essay “Free Black Communities in Rhode Island” for more information [link]

- 16Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:7

- 17The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019:50

- 18Juneteenth.com. “The History of Juneteenth.” Electronic document. Accessed August 5, 2020 [link]

- 19Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018:7-8