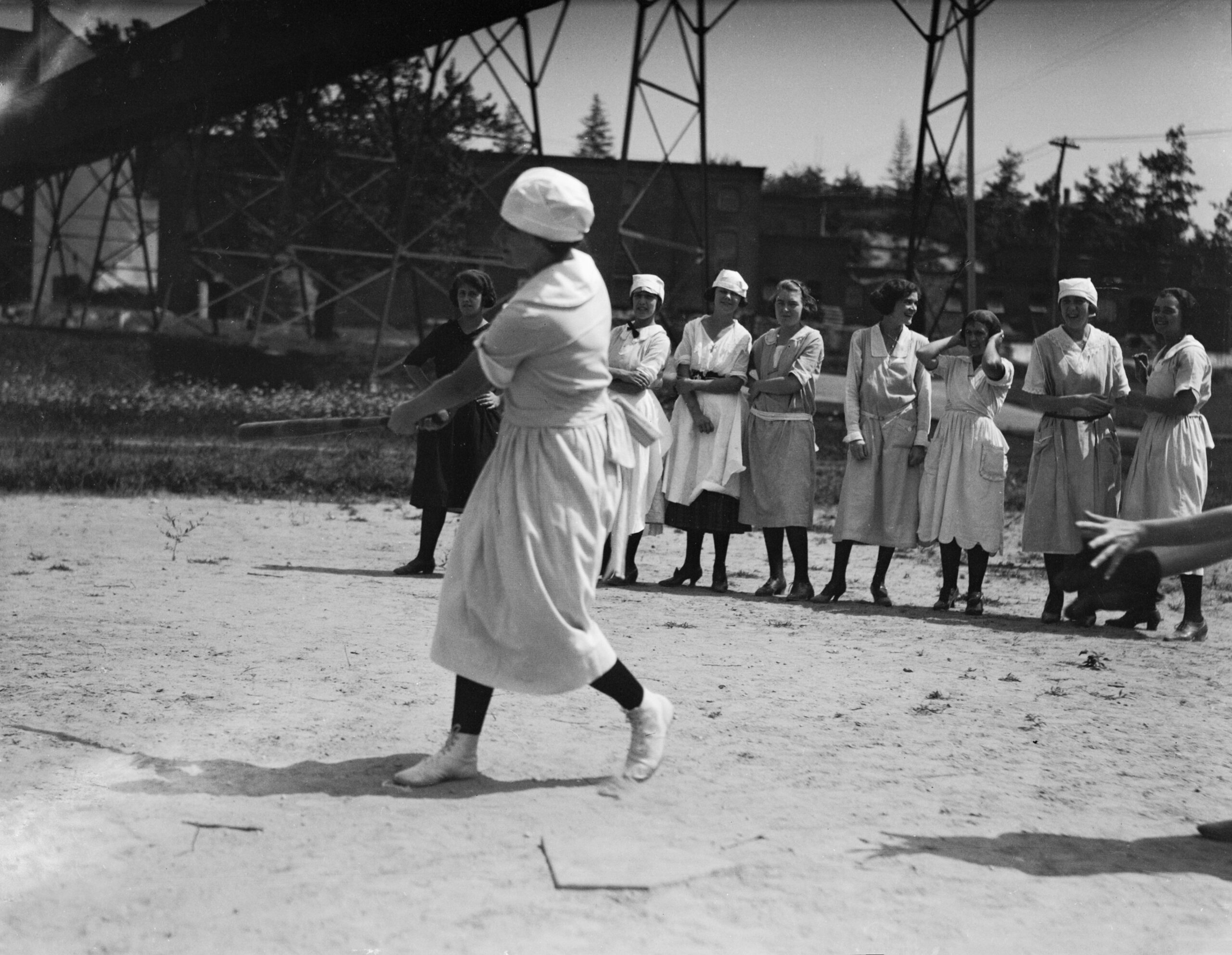

Women Employees Playing Baseball

This photo depicts women employees of Sayles Finishing Plants (Saylesville, RI) playing baseball at lunch on Sep. 15, 1921. Mills encouraged recreational activities in an attempt to keep employee morale high.

Labor Rights and Women’s Suffrage

Essay by Talia Brenner, Brown University Alumna

The movements for working women’s rights and women’s suffrage have been connected since at least the 1800s. Many women activists worked for both causes at the same time, recognizing that women needed more than voting rights alone.

By the late 1800s, Rhode Island’s industrialization had changed the lives of most women. Manufacturers built more and more factories across the state and replaced farming as a way of life. Many working-class women could no longer afford to work in domestic and farming settings and instead had to find jobs in mills. By 1900, Rhode Island had an especially large percentage of women who worked outside the home.1Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History39, no. 2 (1980): 43

Many of these female factory workers were immigrants or first-generation Americans. Since it was not yet standard for all American teenagers to go to school, many working-class girls would drop out of school in their early teens and immediately begin to work in factories. A woman named Mary, who had been a teenage factory worker, quoted a childhood neighbor as saying, “You were fourteen on Saturday, had a party on Sunday, and you’d be in Coats [a local mill] on Monday.”2Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History 39, no. 2 (1980): 44 In factories, young women worked at machines in highly uncomfortable positions, often standing and inhaling dust for ten to twelve hours per day. Other working-class women, particularly Black and Irish women, found work as waitresses and domestic servants.3Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History 39, no. 2 (1980): 48

Middle-class women who had more access to education worked as nurses and office workers. Many of these middle-class jobs and training programs openly excluded Black women.4Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History39, no. 2 (1980): 48 Even though their jobs were more respected than factory and domestic work, middle-class women still dealt with gender discrimination in the workplace.

Gertrude Motta, who had worked as an office worker in Providence, described her office’s rigorous pace of work. “These stacks of inventories came in,” Motta had said in an interview, “and you’d have to get through with them in a day. So you—you build up speed on them.”5Paul M. Buhle, “Working lives: An Oral History of Rhode Island Labor” in RI History vols. 45-46 (1986-1988): 18 She also talked about a supervisor the women workers feared. “If you had to go to the bathroom in between [twice-a-day breaks], you had to ask [the supervisor],” she said. “That was kind of embarrassing.”6Paul M. Buhle, “Working lives: An Oral History of Rhode Island Labor[2] ” in RI History vols. 45-46 (1986-1988): 19

Women from different social classes protested these working conditions. Female factory workers protested for their labor rights. They focused on liveable wages, safer workplace environments, shorter workdays and more frequent breaks, and protection from male supervisors’ harassment. Some upper-class women, who could afford to not work for wages, also advocated for female worker rights. These upper-class women were known as social reformers because they were attempting to reform parts of society.

Sometimes women activists directly connected their protests to the women’s suffrage movement. Working-class women joined groups such as the Rhode Island Council of Women, a women’s club that worked with suffragists. Some suffrage organizations also created programs to help struggling working women. The Rhode Island Young Women’s Christian Temperance Union, a subgroup of the pro-suffrage Women’s Christian Temperance Union, provided low-cost lunches to poor women on 149 Broad St. in Providence7Welcome Arnold Greene et al., The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years, (Providence: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1886): 223 [link] These suffragists did not want their movement only to include wealthy women who had more time to go to meetings and protests.

In addition, some upper-class social reformers claimed that the causes of labor rights and women’s suffrage were connected. Elizabeth Buffum Chace was a social reformer and suffragist who, later in her life, spoke out against her wealthy mill-owning family’s poor treatment of female workers. Chace declared in her writings and speeches that awful working conditions contributed to women’s difficult lives just as the lack of voting rights did.8Elizabeth C. Stevens, “‘Was She Clothed with the Rents Paid for These Wretched Rooms?’: Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Lillie Chace Wyman, and Upper-Class Advocacy for Women Factory Operatives in Gilded Age Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History 52, no. 4 (1994): 128. Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s papers, including some of these writings, are available at the RIHS Research Center.

Other activists for women’s labor rights did not connect their causes to women’s suffrage. In 1911, the Providence Journal interviewed Grace C. Strachan, a district superintendent of Brooklyn public schools, who had just won “equal pay for equal work” for teachers there, meaning that women teachers could no longer be paid less than men who did the same job. Strachan had just taken her campaign for equal pay to Providence. Journalist Mary Katherine Woods wrote in the article that Strachan emphasized that she was not a suffrage activist. “The battle, Miss Strachan and her fellow teachers are quick to explain, has no necessary connection with the cause of women’s suffrage,” Woods wrote.9Providence Journal 12 November 1911 p.45 “The Equal Pay for Equal Work Crusade” Yet it is hard to believe that Strachan did not agree with the suffrage movement. What is more likely is that she did not publicly associate herself with it because she did not want to connect her equal pay campaign to a widely unpopular women’s suffrage movement. She also may not have wanted to damage the women’s suffrage movement by associating it with her unpopular campaign for equal pay for equal work.

Suffragists, who were also labor rights advocates, knew that they were fighting for two causes that were often unpopular. The Rhode Island state referendum on women’s suffrage in 1887 had failed by a vote of 6,889 to 21,957.10Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., The History of Woman Suffrage, 1883-1900, (Rochester, N.Y.: Susan B. Anthony [1902]), 4:909-912) Women’s labor movements faced big challenges from influential mill owners and politicians who were not concerned with workers’ rights.

Activists in this situation often used respectability politics. Respectability politics are when activists show how unthreatening and “respectable” they are in order to help their cause gain more support. Strachan, a labor rights activist, was using respectability politics when she claimed that she was not a suffragist. Some suffragists used respectability politics when they tried to show people that they were not going to challenge the social orders of class, race, and gender. Many wealthy women suffragists did not speak out in favor of working women’s rights. Similarly, many white suffragists did not advocate for black women’s rights. Respectability politics also led suffragists to present themselves as proper wives and mothers in their public appearances, wearing highly feminine white dresses and sashes, in order to prove that they would not change the traditional family order. Respectability politics meant that women had to choose which causes to support and which to exclude in order to get the best possible support for their initiatives. Women from different social classes in the suffrage movement were sometimes united, and some suffragists never used respectability politics in their activism. Nonetheless, many wealthy women’s use of respectability politics meant that divisions in the suffrage movement continued.

The struggle for women workers’ rights, like the struggle for women’s suffrage, is still ongoing. Even today, women workers in the U.S. face unique problems in the workplace, such as sexual harassment and pregnancy discrimination. Women working in majority-female careers like caretaking and domestic work deal with low wages and long hours, much like women working in Rhode Island mills one hundred years ago. And even though it is now illegal to pay women less money than men for working the same jobs, on average, women, especially women of color, do not get promotions and pay raises as quickly as men do.

Yet, even though working outside the home presented women with many challenges, it also helped many women find a greater sense of independence than they had before. Organizing for labor rights and women’s suffrage helped women build connections with each other and show their power in working toward common goals. Women continued to use these strengths in later feminist movements through the present day.

Terms:

Suffrage – the right to vote

Industrialization – when an economy changes from being mainly farming work to being mainly factory work

Domestic – based in someone’s home. Domestic work involves cooking, cleaning, laundry, raising children, gardening, etc.

Reform – positive change

Referendum – when the government asks voters to decide a law by direct vote (instead of elected representatives deciding about the law)

Respectability politics – when activists show how unthreatening they are in order to help their cause gain more support

Questions

Define “respectability politics” in your own words. Can you think of other examples of respectability politics in U.S. history?

What kind of “equal pay” activism are feminists in the U.S. doing today? Research “Equal Pay Day” and make sure you identify when Equal Pay Day for Black and Latina women will be this year. Equal Pay Day is one way of showing how the wage gap affects people’s lives. What are other creative ways to teach people about the wage gap?

In what ways did the women’s labor movement contribute to women’s suffrage?

- 1Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History39, no. 2 (1980): 43

- 2Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History 39, no. 2 (1980): 44

- 3Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History 39, no. 2 (1980): 48

- 4Sharon Hartman Strom, “Old Barriers and New Opportunities: Working Women in Rhode Island, 1900-1940,” Rhode Island History39, no. 2 (1980): 48

- 5Paul M. Buhle, “Working lives: An Oral History of Rhode Island Labor” in RI History vols. 45-46 (1986-1988): 18

- 6Paul M. Buhle, “Working lives: An Oral History of Rhode Island Labor[2] ” in RI History vols. 45-46 (1986-1988): 19

- 7Welcome Arnold Greene et al., The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years, (Providence: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1886): 223 [link]

- 8Elizabeth C. Stevens, “‘Was She Clothed with the Rents Paid for These Wretched Rooms?’: Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Lillie Chace Wyman, and Upper-Class Advocacy for Women Factory Operatives in Gilded Age Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History 52, no. 4 (1994): 128. Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s papers, including some of these writings, are available at the RIHS Research Center.

- 9Providence Journal 12 November 1911 p.45 “The Equal Pay for Equal Work Crusade”

- 10Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., The History of Woman Suffrage, 1883-1900, (Rochester, N.Y.: Susan B. Anthony [1902]), 4:909-912)