Rhode Island and the Industrial Revolution

Essay by Gail Fowler Mohanty, Senior Lecturer, Rhode Island School of Design; Adjunct Faculty, Bryant University

“Hark! Do you hear the fact’ry bell?

Of Wit and Learning ‘tis the Knell”

—Thomas Man, 18331Man, Thomas. A Picture of a Factory Village to which is annexed remarks on lotteries. Providence: Printed for the Author, 1833.

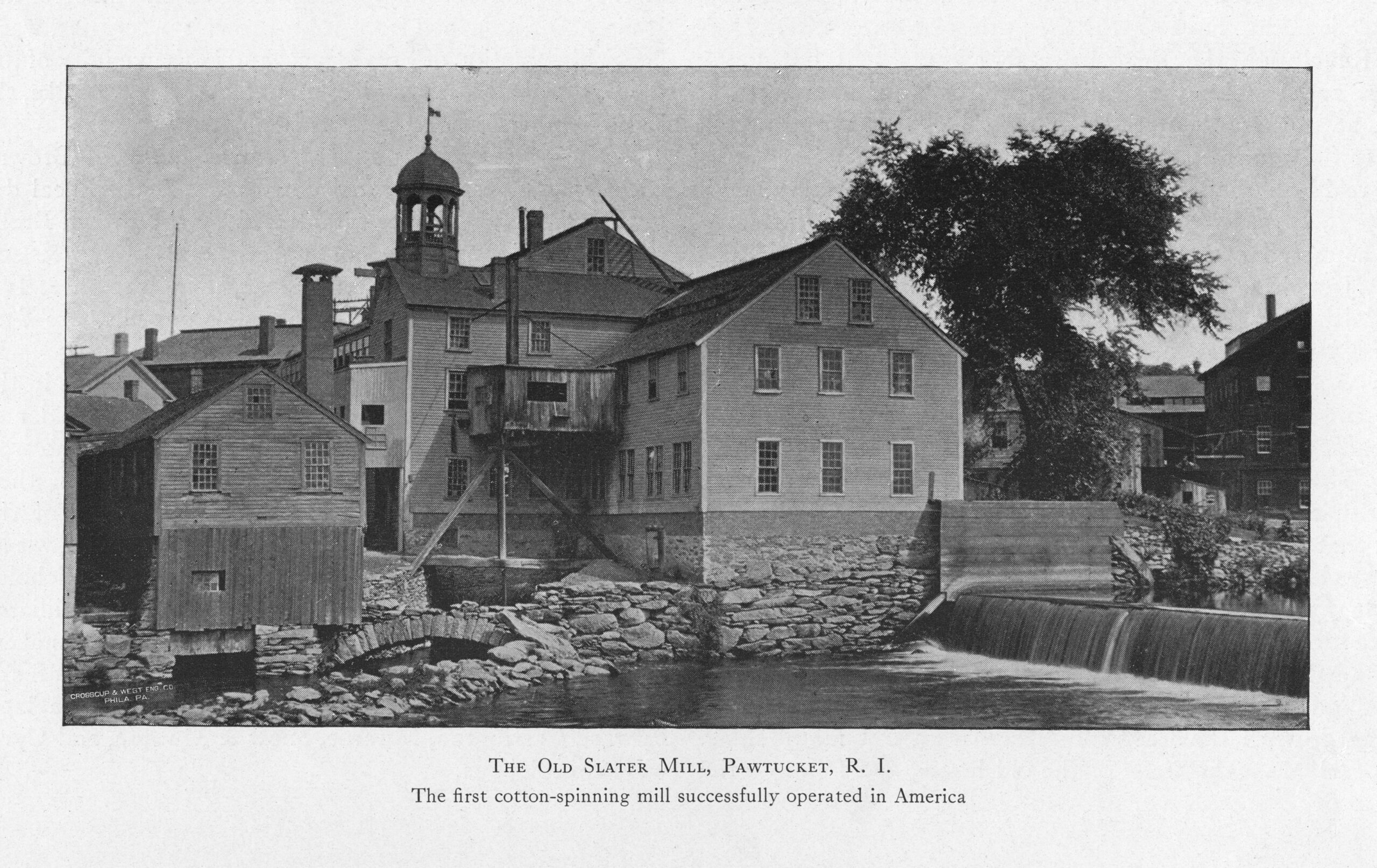

Slater Mill

Read about Slater Mill and the Rhode Island System here

On December 20, 1790, immigrant Samuel Slater successfully spun cotton into yarn by machine in Rhode Island for the first time. Using today’s standards of mass production, this might seem small. But by the criteria of the day, it marked tremendous innovation developed by Slater along with Rhode Island artisans. Prior to this, cotton was processed and spun at home or in small shops using hand tools and the spinning wheel. Machine-spun cotton allowed for greater quantities with less manpower. This step in industrialization was so significant that two hundred years later, the United States Post Office chose an image of Slater’s Mill to represent Rhode Island on a stamp commemorating the bicentennial of our statehood.2The postage stamp, initially issued on May 29, 1990, commemorates Rhode Island’s statehood and Rhode Island’s ratification of the US Constitution. David Macaulay, author of The Way Things Work, (Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1988) and Mill, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983) designed the cancellation mark, depicting a detail of a spinning throstle to symbolize successful cotton spinning. Equally important is that Slater’s achievement was dependent upon artisans and machinists who lived in the state. This success story credits Rhode Island with the birth of American Industrialization. Yet, the seeming simplicity of this tale ignores the complexity of industrial development and its broad-ranging effects.

The American Industrial Revolution is comprised of more than manufacturing cotton yarn. It is part of a series of systems that transformed the nation’s economic base, altered the balance of trade, and introduced a cash economy. Additionally, mechanized production generated tremendous technological innovation; and a workforce of local laborers spawned organized and efficient work environments. A gradual diversification of Rhode Island’s economy and the rise of manufacturing began by the mid-18th century. These first changes foreshadowed the Industrial Revolution that was to come and are connected to Rhode Island’s small size and limited resources.

“Slave Cloth”

Read about how Rhode Island established trade with slave holders in the Southern U.S. here

Ample water power in the many streams that traverse the state and an extensive coastline with safe harbors were among the characteristics that lead Rhode Island’s economy to change from one based on farming, trade and fisheries. In addition, Rhode Island’s land soil quality and short growing season spurred residents to expand economically in ways that addressed the limitations of farming in the area. These restrictions stimulated the growth of commerce and manufacturing by machine and enabled Rhode Island to lead the movement toward industrialization. The state initiated economic change even before the establishment of the United States.

Rhode Island’s growing population of land-poor and landless people became an army of workers for industrialized manufacturing. The small scale of these early enterprises made them vulnerable to foreign competition, however. To counter this, the federal government sought ways to encourage New England and the Middle Atlantic States to develop competitive businesses for consumers at home and abroad. They did this in the hope that this would create a favorable balance of trade and, thus, economic independence for the country. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton formed a plan that encouraged states to increase manufacturing.

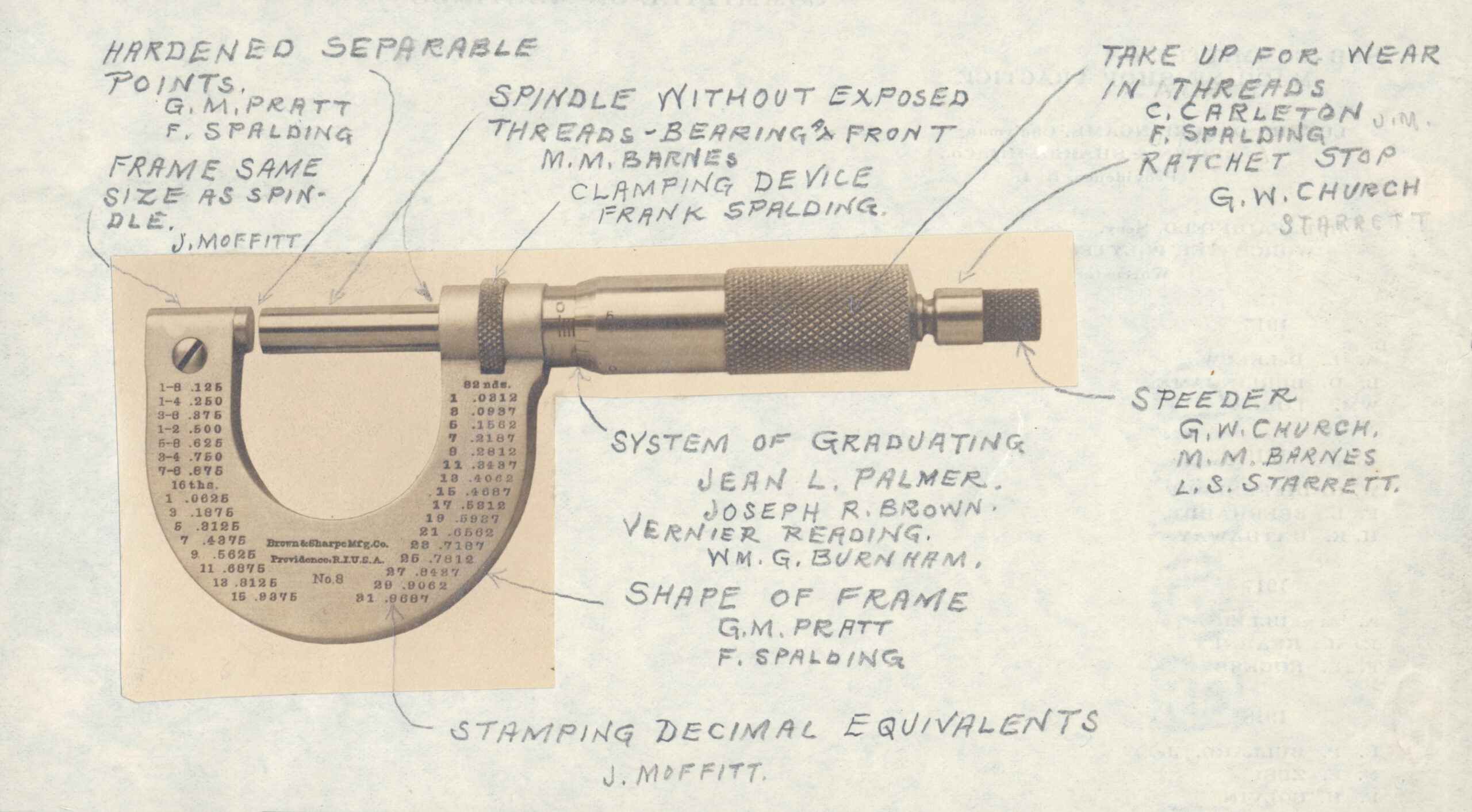

Micrometer

Read more about machine shops and inventions to increase production of goods here

Completed in 1791, Hamilton’s “Report on the Subject of Manufactures” constituted the third part of his economic proposal for the United States.3The other two elements of the plan include establishing 1. the federal monetary system and the Bank of the United States, and 2. the federal government absorption of state debts incurred during the American Revolution. His report included information about the manufacturing taking place in each state. In Rhode Island, it was noted that a wide range of manufacturing businesses had started by the mid-18th century. Limited in size and technology, many firms combined mechanization with hand production. The manufacturing that developed in Providence included the production of cotton and woolen textiles, iron, steel and finer metalworking, and shipbuilding, among other businesses.4List of manufacturing in Rhode Island from the Report of Committee on Manufactures of Providence, Rhode Island, in July of 1790. The Report is reprinted in Arthur Harrison Cole, editor, Industrial and Commercial Correspondence of Alexander Hamilton, Anticipating his Report on Manufactures. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, Publishers, 1968 reprint of 1928 edition. 71-88. The list includes: wool and cotton manufacturing, iron slitting, hat making, paper manufacture, cabinetry, cordage, coppersmiths, pewterers, card making, brass founders, fire engines, soap and candle making, coach and chaise making, chocolate manufacture, clock making, edge tools, nails, boots and shoes, block making, shipbuilding, tanning and currying, saddle and harness making. As an example of small-scale manufacturing, which involves both hand and mechanized processes, Brown and Almy reported the manufacture of 7,823 yards of handwoven cotton/linen blended fabrics during ten months of operation in 1791. In this case, cotton spinning is performed by machine, and linen warps and blended fabrics are accomplished by hand. Woolen cloth manufactured in Providence 30,000 yards of handwoven wool in 12 months of 1790. At first, after the publication of the 1791 report, industrialization expanded slowly since neither federal nor state subsidies encouraged their development. After the founding of Pawtucket’s 1793 mill, only the Browns and Slater started other Rhode Island textile manufacturing businesses. However, production expanded shortly after. By 1809, there were seventeen mills operating within a 30-mile radius of Providence. By 1811, Zachariah Allen indicated that there were thirty-six mills powering 31,602 spindles, and in 1812, there were thirty-eight mills running 48,034 spindles within the same radius.5Cotton Manufacturing within a thirty-mile radius of Providence, 14 Nov. 1809. Miscellaneous Manuscript. Rhode Island Historical Society. Providence, Rhode Island.6Allen, Zachariah. Historical Theoretical and Practical Account of Textile Fabrics. Zachariah Allen Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Rhode Island. These figures are limited only to textile industrialization and do not reflect other sorts of manufacturing within the state. But, these figures indicate rapid growth. At this point, Rhode Island’s textile mills focused on manufacturing thread or yarn.

Blacksmiths and machinists, who had established businesses making nails, anchors, chains, and other materials associated with shipbuilding, also made the machinery for the industrial mills. In 1790, Samuel Slater used machinists from the Wilkinson Machine Shop in Pawtucket village. Artisans refined textile fiber processing and spinning machines acquired by Moses Brown between 1788 and 1789 to achieve the result of spinning yarn well. The relationship forged in Pawtucket mirrors what grew later between machine shops and mills throughout Rhode Island. Mill business owners also hired machinists to repair existing equipment. During repair, machinists often saw means of creating improvements or new inventions. As a result, machine shops became laboratories of invention and produced important patents credited to Rhode Island artisans.7Jeremy, David J. Transatlantic Industrial Revolution: The Diffusion of textile technologies between Britain and America 1790-1830s. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979. On page 215, Jeremy discusses the importance of John Thorp’s invention of the ring spindle in particular.

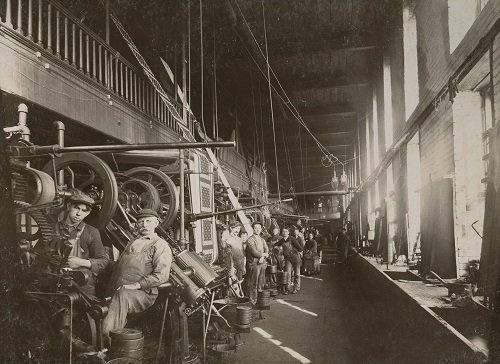

Child Laborers

Read more about child labor here

Kelley v. Silver Spring Court Notes

Read more about working conditions in mills here

Using his experiences as an apprentice in Jedediah Strutt’s cotton spinning mill in England, Samuel Slater employed five to seven child laborers aged 7 to 12 working machines in a disciplined and organized work environment for his 1790 cotton spinning demonstration. While employing child labor was not a new concept, the introduction of such workers into a factory workplace was. The children, offspring of local artisans, proved challenging to acquaint with factory work. The introduction of workers of any age into industrialized workspaces proved difficult for managers who required discipline, an organized system of work, and many hours a day. Slater’s workers came from the locality of his spinning mill, but ultimately a larger army of mill labor came from outlying farms. The values of time and work instituted in factories differed from farm work which was governed by sun and season.

By the 1820s, managers had developed a workplace culture and established it in factories. Between 1790 and 1830, mill workers accepted the time requirements but were bothered by changes that decreased pay, required increased production, or heightened danger.8Kulik, Gary. Factory Discipline in the New Nation: Almy, Brown and Slater and the First-Mill Workers. Massachusetts Review, 28(1987): 164-184; Gutman, Herbert. Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America, 1815-1919. American Historical Review 78(1973): 531-588; and Thompson, E.P. Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism, Past and Present 38(1967): 56-97. By the first quarter of the 19th Century, workers voiced dissatisfaction with the work and working conditions by turning out or not showing up for work. The earliest “revolt” recorded in New England occurred in 1821 in Massachusetts.9Jeremy, David J and Polly C. Darnell. Visual Mechanic Knowledge the Workshop Drawings of Isaac Ebenezer Markham (1795-1825). New England Textile Mechanic. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2010. 14. An 1821 strike at the Boston Manufacturing Company in Waltham, Massachusetts, led women to walk out over a change in the way they were paid. Isaac Markham, a machinist at the firm, described the incident in a letter to his brother in Middlebury, Vermont. Markham describes how unfair the company was to the employees. They cut the pay of unmarried men without forewarning them and did the same to women who worked there, “but they as one revolted and the works stopped 2 days in consequence.” In 1824, a second strike occurred in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Five hundred workers turned out of spinning and weaving mills and kept the mills closed for a week. Women power loom weavers led this resistance. Artisans in Pawtucket Village proved sympathetic to the laborers’ cause. This particular event highlights community solidarity and foreshadows the rise of unionization by showing how important population size is when pressing the case for change.10Commons, John R. et al. History of Labor in the United States, vol. 1, New York: 1918, 156 and Kulik, Gary. Pawtucket Village and the Strike of 1824: The Origins of Class Conflict in Rhode Island. Radical History Review 17(1978): 5-38. Striking also provides a good barometer of the growth of a distinct working class, which gains effectiveness and power in their numbers. Ultimately, workers see the benefits of group rebellion and begin to form local union-like organizations. In the late 1830s and ‘40s, the working class used this understanding of power in numbers to gain a voice in the government and use their voting power to institute change.11In addition to these two strikes, there were two additional examples from the 1830s in Lowell also involving women. In 1834 and 1836, the issue related to pay cuts in an effort to increase productivity. Dublin, Thomas. Women at Work The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Workers’ Strike

Read more about labor unions and strikes here

The impact of this early strike was felt in the formation of a regional labor organization, the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics, and other Workingmen in Pawtucket during the 1830s. In 1833, Thomas Man of Providence wrote “A Picture of a Factory Village”12Man, Thomas. A Picture of a Factory Village to which is annexed remarks on lotteries. Providence: Printed for the Author, 1833. highlighting the dangers, dullness, and degradation of factory work. The author saw the irony between our Founding Fathers’ vision for liberty and equality and the lack of it for the working class. By the 1840s, Pawtucket was a center for the working class’s goals of gaining a voice in government by expanding the power of the now large population of local and immigrant workers. These goals were brought to fruition by the Dorr Rebellion of 1840-41. The Dorr War resulted from the growing support of the idea that a substantial percentage of Rhode Island’s citizenry were unable to vote and to have a say in government. As a result of the Dorr Rebellion, Rhode Island’s 1663 charter was replaced by a reframed constitution that gained more people the right to vote.13Ibid. “For Liberty our fathers fought,/Which with their blood they dearly bought?/A slave at morn, A slave at eve./It doth my inmost feelings grieve./The blood runs chilly from my heart,/To see fair Liberty, depart;” Also, Gary Kulik, “Rhode Island’s First Strike: The Pawtucket Turn Out of 1824.” A History of Rhode Island Working People, Paul Buhle, Scott Molloy and Gail Sansbury, editors. Providence, RI: Regine Publishing Company, 1983. 3-4.

Dorr Rebellion

Read more about the Dorr Rebellion here

By the 1860s, industrialization continued but changed in the scale of manufacture, architecture, and power. During the 1830s, steam power removed the geographic limitations that water power imposed, enabling factories to move to transportation hubs and urban centers. Now, brick mills could be built anywhere and house larger equipment. The number of workers laboring in the mills increased in response to the growth of the economy and the effects of increased production to outfit the Civil War. This marked the beginnings of what was called the Second Industrial Revolution. During the period of Reconstruction, business owners saw opportunity in moving south to be closer to raw materials and a less expensive workforce. Because of this, many of Rhode Island’s larger mill buildings were subdivided to house multiple businesses. Using Slater mill as an example of this change, from the late 19th century until the first quarter of the 20th, the building held manufacturing enterprises that included ring and cap spindle manufacture, braiding and fringe production, including coffin trimmings, and bicycles. Manufacturing continued to be important to Rhode Island’s economy through much of the twentieth century, but the state was no longer at the forefront of change.

Terms:

Mass production: Producing goods in large amounts or quantities

Water power: Power from water was used to run the machinery that made goods such as textiles before steam or electricity

Traverse: Cross

Textile: Woven cloth

- 1Man, Thomas. A Picture of a Factory Village to which is annexed remarks on lotteries. Providence: Printed for the Author, 1833.

- 2The postage stamp, initially issued on May 29, 1990, commemorates Rhode Island’s statehood and Rhode Island’s ratification of the US Constitution. David Macaulay, author of The Way Things Work, (Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1988) and Mill, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983) designed the cancellation mark, depicting a detail of a spinning throstle to symbolize successful cotton spinning.

- 3The other two elements of the plan include establishing 1. the federal monetary system and the Bank of the United States, and 2. the federal government absorption of state debts incurred during the American Revolution.

- 4List of manufacturing in Rhode Island from the Report of Committee on Manufactures of Providence, Rhode Island, in July of 1790. The Report is reprinted in Arthur Harrison Cole, editor, Industrial and Commercial Correspondence of Alexander Hamilton, Anticipating his Report on Manufactures. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, Publishers, 1968 reprint of 1928 edition. 71-88. The list includes: wool and cotton manufacturing, iron slitting, hat making, paper manufacture, cabinetry, cordage, coppersmiths, pewterers, card making, brass founders, fire engines, soap and candle making, coach and chaise making, chocolate manufacture, clock making, edge tools, nails, boots and shoes, block making, shipbuilding, tanning and currying, saddle and harness making. As an example of small-scale manufacturing, which involves both hand and mechanized processes, Brown and Almy reported the manufacture of 7,823 yards of handwoven cotton/linen blended fabrics during ten months of operation in 1791. In this case, cotton spinning is performed by machine, and linen warps and blended fabrics are accomplished by hand. Woolen cloth manufactured in Providence 30,000 yards of handwoven wool in 12 months of 1790.

- 5Cotton Manufacturing within a thirty-mile radius of Providence, 14 Nov. 1809. Miscellaneous Manuscript. Rhode Island Historical Society. Providence, Rhode Island.

- 6Allen, Zachariah. Historical Theoretical and Practical Account of Textile Fabrics. Zachariah Allen Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Rhode Island.

- 7Jeremy, David J. Transatlantic Industrial Revolution: The Diffusion of textile technologies between Britain and America 1790-1830s. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979. On page 215, Jeremy discusses the importance of John Thorp’s invention of the ring spindle in particular.

- 8Kulik, Gary. Factory Discipline in the New Nation: Almy, Brown and Slater and the First-Mill Workers. Massachusetts Review, 28(1987): 164-184; Gutman, Herbert. Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America, 1815-1919. American Historical Review 78(1973): 531-588; and Thompson, E.P. Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism, Past and Present 38(1967): 56-97.

- 9Jeremy, David J and Polly C. Darnell. Visual Mechanic Knowledge the Workshop Drawings of Isaac Ebenezer Markham (1795-1825). New England Textile Mechanic. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2010. 14. An 1821 strike at the Boston Manufacturing Company in Waltham, Massachusetts, led women to walk out over a change in the way they were paid. Isaac Markham, a machinist at the firm, described the incident in a letter to his brother in Middlebury, Vermont. Markham describes how unfair the company was to the employees. They cut the pay of unmarried men without forewarning them and did the same to women who worked there, “but they as one revolted and the works stopped 2 days in consequence.”

- 10Commons, John R. et al. History of Labor in the United States, vol. 1, New York: 1918, 156 and Kulik, Gary. Pawtucket Village and the Strike of 1824: The Origins of Class Conflict in Rhode Island. Radical History Review 17(1978): 5-38.

- 11In addition to these two strikes, there were two additional examples from the 1830s in Lowell also involving women. In 1834 and 1836, the issue related to pay cuts in an effort to increase productivity. Dublin, Thomas. Women at Work The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

- 12Man, Thomas. A Picture of a Factory Village to which is annexed remarks on lotteries. Providence: Printed for the Author, 1833.

- 13Ibid. “For Liberty our fathers fought,/Which with their blood they dearly bought?/A slave at morn, A slave at eve./It doth my inmost feelings grieve./The blood runs chilly from my heart,/To see fair Liberty, depart;” Also, Gary Kulik, “Rhode Island’s First Strike: The Pawtucket Turn Out of 1824.” A History of Rhode Island Working People, Paul Buhle, Scott Molloy and Gail Sansbury, editors. Providence, RI: Regine Publishing Company, 1983. 3-4.