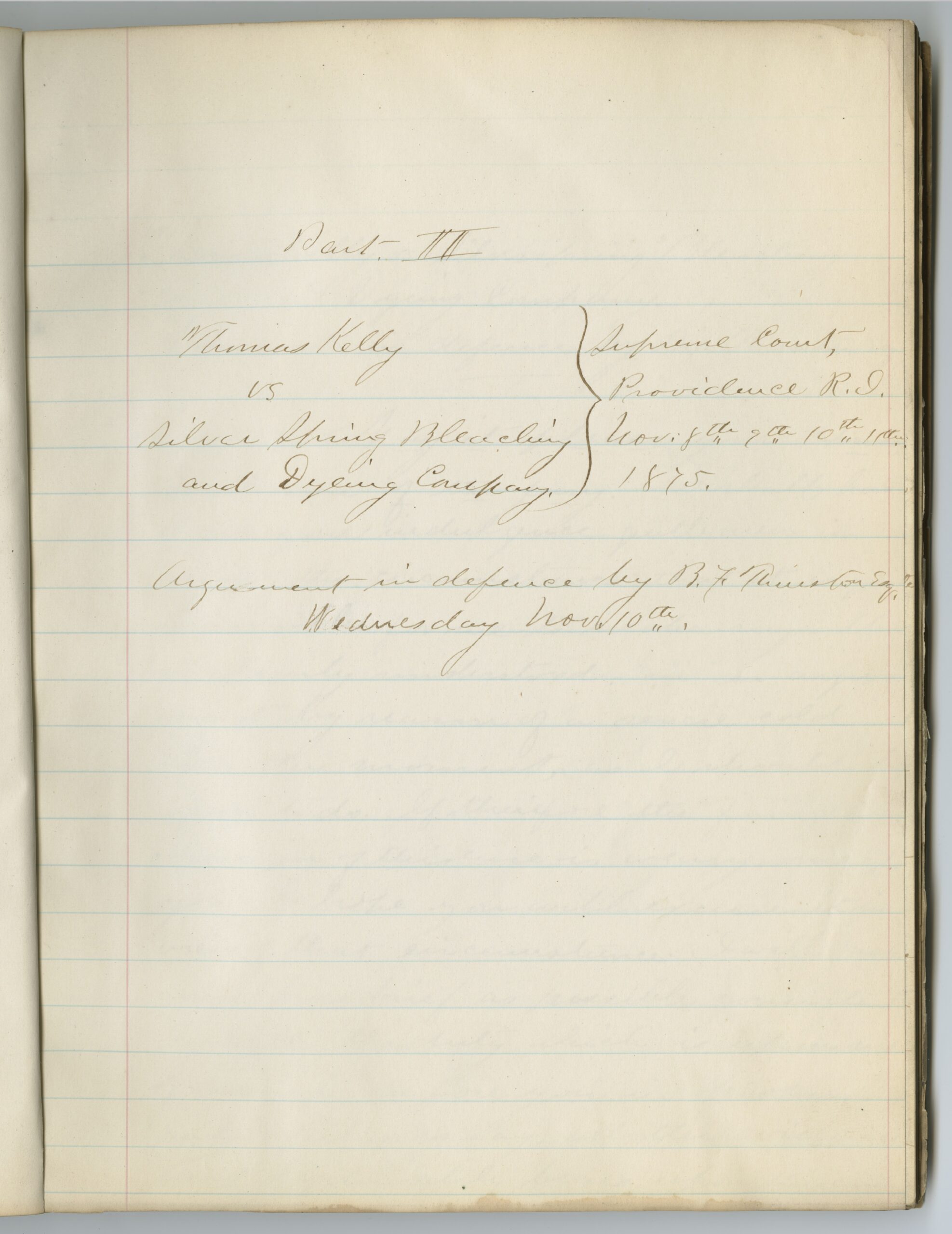

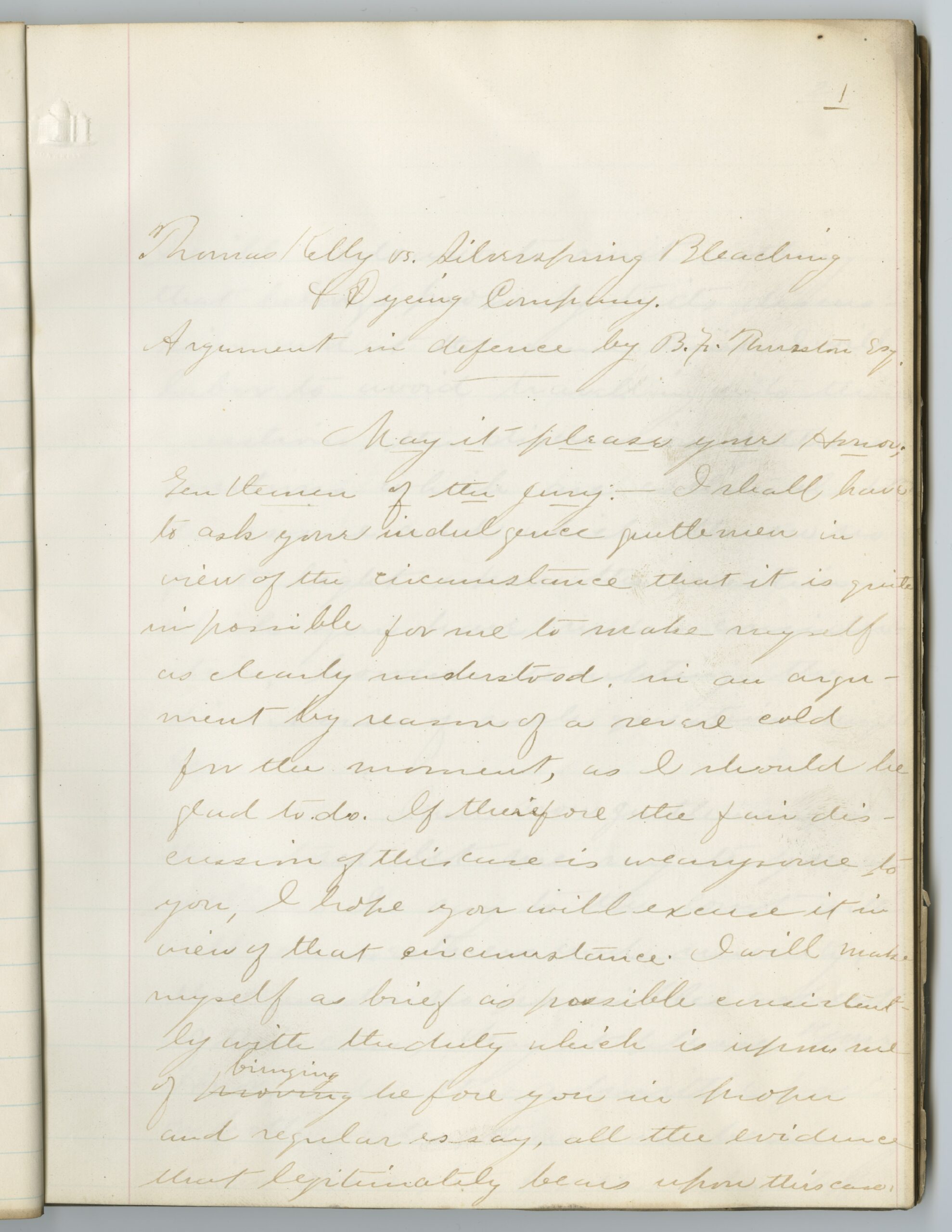

Kelley v. Silver Spring Court Notes

This image is the cover of a set of notes taken during a court case, “Kelley v Silver Spring.” Thomas Kelley, the man for whom the case is named, worked at Silver Spring Bleaching and Dyeing Company, and suffered a terrible accident which crushed his hand. Since the accident was caused by faulty machinery, he sued the company, asking to be compensated since he could no longer work because of the injury. Unfortunately, situations like these were not uncommon. Court notes like these are able to provide us insights into the ways that companies and workers dealt with the dangers that came along with factory work.

“Whatever the risk, he must be held to have consented to it”: Kelley v. Silver Spring

Essay by Talya Housman, PhD Candidate in the Department of History at Brown University

On the 12th of January 1874, Thomas Kelley arrived at work at the Silver Spring Bleaching and Dyeing Company as usual. It was just after seven in the morning, and the sun had yet to rise fully. Steam poured off the vats of dyeing cloth, making it difficult for Kelley to see, but as a seasoned employee of four years, he knew the machines by feel. Kelley picked up a rope that he had hitched to the gears of the machine a few weeks prior when the bottom of the machine had broken open, exposing the gears. Using a piece of rope was a common makeshift solution to the problem of exposed gears and Kelley was far from the only employee at Silver Spring to use it. On this particular day, though, as Kelley lifted the rope, his little finger caught in the corner gears and pulled his hand in after it, crushing his hand.1Kelley v. Silver Spring Co., 12 R.I. 112 (20 April 1878), 2. [link] Thomas Kelley was thirty years old.

Maiming was not an uncommon fate for industry employees, but it was a grim one that made future employment almost impossible. Kelley decided to sue the Silver Spring Bleaching and Dyeing Company for compensation. If he won this lawsuit, Silver Spring would be required to pay him for the loss of his ability to work and provide him with an income. After all, had their machine not been broken, Kelley would still have had the use of his hand.

However, since Kelley’s fate was not at all uncommon, Silver Spring was ready.

They employed Samuel Ames III, an attorney who specialized in defending companies against work-related industry lawsuits. Throughout his career, Ames would defend not only Silver Spring but also Builders Iron Foundry and Worsted Mills, to name a few. Ames usually won, frequently coming to settlement without ever having to set foot in a courtroom. This was partially due to his talent as a lawyer, but Ames had the additional aid of a legal system that favored employers. Companies had strong faith in both Ames and the legal system to crush the complaints of their employees. The insurance company manager at Builders Iron Foundry wrote to Ames about a particular case saying, “I have confidence that if it comes to a hearing you will prevail as usual.” 2Russell Gray, Letter to Samuel Ames Esq., 10 February 1896, in Samuel Ames Family Papers, MSS 259, Samuel Ames III, Box 3, “Legal Papers – Cases: Raia vs. Builders Iron Foundry,” Rhode Island Historical Society.

Up to this point, Kelley’s story could have been anyone’s. Many workers were injured in industrial accidents. Many faced a legal system balanced against them. However, the outcome of Kelley’s case was to change the fate of every injured industrial worker who came after him.

On April 20th, 1878, the Supreme Court of Rhode Island ruled in favor of Silver Spring and denied Kelley’s claim. While they acknowledged that Silver Spring’s machinery had indeed injured Kelley and that the machinery had been broken, the court ruled that “it was a danger incident to his employment which he voluntarily incurred…and therefore, whatever the risk, he must be held to have consented to it as one of the perils of his employment.”3Kelley v. Silver Spring Co., 12 R.I. 112 (20 April 1878), 7-8. [link]

In other words, because Kelley’s work was obviously dangerous, in accepting his job, he accepted the risk that he might be injured in service. This was a legal principle called “assumed risk,” and Kelley’s case helped the courts define what injuries fell into a category of “assumed risks” for industrial work. This meant workers did not have the right to compensation from the company for injuries that fell into the “assumed risk” category. Legal sources reported that in Kelley v. Silver Spring “the doctrine of assumed risks was fully settled and has since been followed without question.”4J K Angell, T Durfee, J P Knowles, S Ames, C S Bradley, and J F Tobey, Reports of Cases Heard and Determined in the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. No. 25 (1904 and 1910); T J. Michie, Railroad Reports: a Collection of All Cases Affecting Railroads of Every Kind, Decided by the Courts of Last Resort in the United States. No. 11 (1904); C B. Whittier, Cases on Common Law Pleading:Selected From Decisions of English and American Courts, 1912. In many cases following Kelley’s, the courts cited this decision to deny workers compensation for industrial accidents. Thankfully, since Kelley’s case, comprehensive workers’ compensation laws have been passed in every US state, beginning with Wisconsin in 1911, and ending with Mississippi in 1948.5Gregory P. Guyton, “A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation,” The Iowa Orthopedic Journal 19 (1999): 106. Worker’s compensation laws give workers the right to be paid if they were injured on the job. In addition, in 1970, Congress created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to set and enforce standards of healthy and safe working conditions for American workers.6See the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) for information. [link]

Sadly, we don’t know the end of Kelley’s story. We don’t know how he fared after he lost his income. However, Kelley represents thousands of workers in Rhode Island and more across the United States who worked in dangerous conditions with little protection. His case demonstrates the ways in which the legal system struggled to adjust to new kinds of labor and new interactions between employers and employees.

Terms:

Maiming: Injuring to an extent that can cause the loss of a body part

Assumed risk: A term used to claim that the injured party understood the risk involved and agreed to take on that risk

Questions:

Why do you think Thomas Kelley decided to sue his employer, Silver Spring Bleaching and Dyeing Company?

Why do you think that Silver Spring had a lawyer ready to defend them, instead of just offering to take care of Mr. Kelley after his accident?

What impact did the court case of Kelley v. Silver Spring have on later industrial accident lawsuits? What do you think about that impact?

- 1Kelley v. Silver Spring Co., 12 R.I. 112 (20 April 1878), 2. [link]

- 2Russell Gray, Letter to Samuel Ames Esq., 10 February 1896, in Samuel Ames Family Papers, MSS 259, Samuel Ames III, Box 3, “Legal Papers – Cases: Raia vs. Builders Iron Foundry,” Rhode Island Historical Society.

- 3Kelley v. Silver Spring Co., 12 R.I. 112 (20 April 1878), 7-8. [link]

- 4J K Angell, T Durfee, J P Knowles, S Ames, C S Bradley, and J F Tobey, Reports of Cases Heard and Determined in the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. No. 25 (1904 and 1910); T J. Michie, Railroad Reports: a Collection of All Cases Affecting Railroads of Every Kind, Decided by the Courts of Last Resort in the United States. No. 11 (1904); C B. Whittier, Cases on Common Law Pleading:Selected From Decisions of English and American Courts, 1912.

- 5Gregory P. Guyton, “A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation,” The Iowa Orthopedic Journal 19 (1999): 106.

- 6See the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) for information. [link]