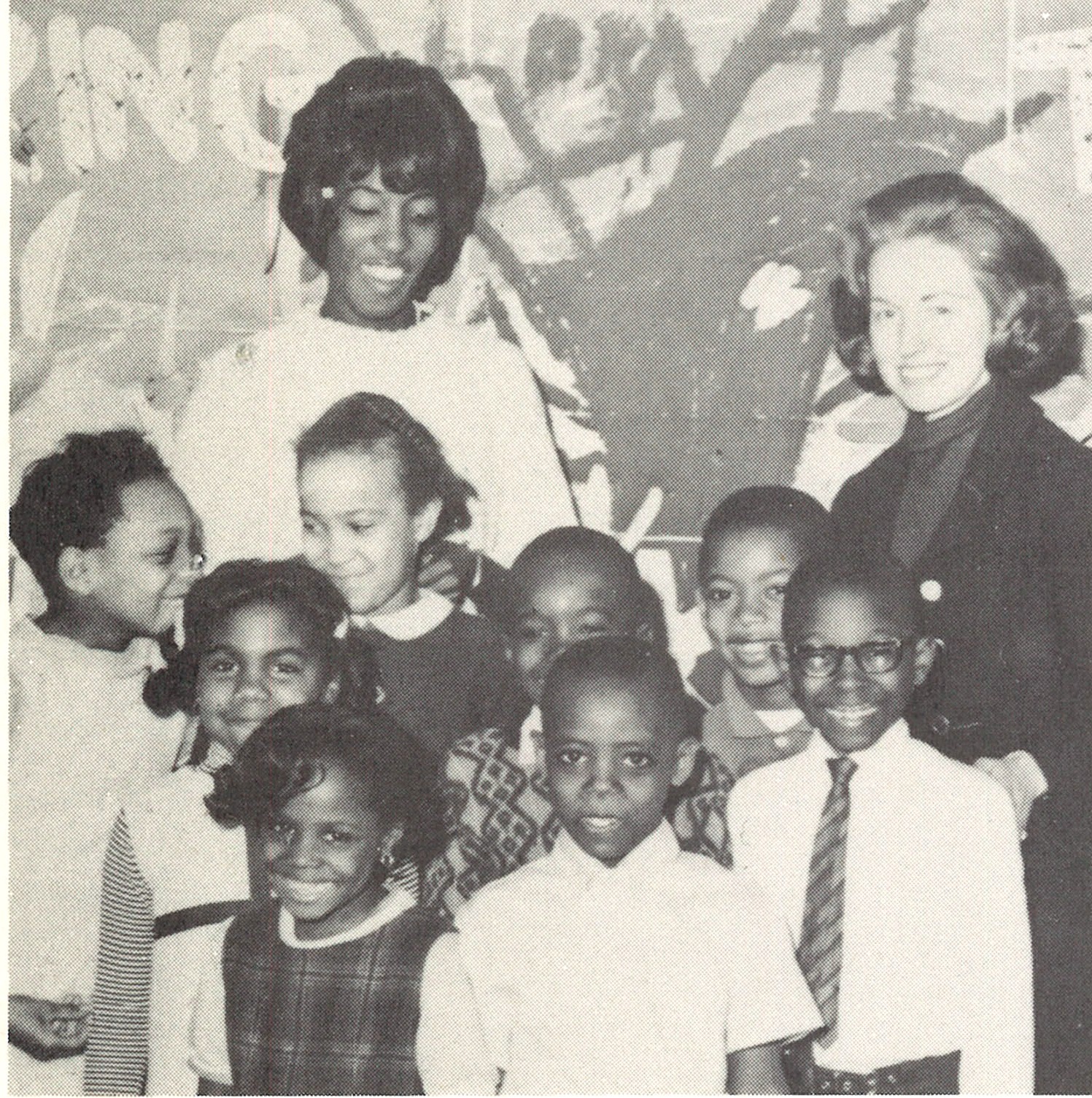

Photograph of Lippitt Hill Redevelopment Project

This is a photograph of a boy watching the construction of the Lippitt Hill Redevelopment Project in which many families, mostly African American, were

forced to move to make room for new construction and building upgrades. This image is from the Providence Redevelopment Agency’s Annual Report, 1960.

Urban Renewal and Rhode Island: A Complicated History

Essay by Miguel Youngs, Public Services Assistant, The Rhode Island Historical Society

Urban renewal throughout the United States has a complicated history and in Rhode Island, it’s no different. Urban renewal is defined as “a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities,” but it is rarely so simple in practice. It is impossible to deny the role that urban renewal initiatives have played in creating an environment of reinforced racial inequality and discriminatory housing practices. This has arguably occurred as a side effect of the larger goal behind urban renewal. Many cities across the country believed that urban renewal could be used as a force of progress that would accelerate society into a more prosperous state where the dilapidation and outdated living conditions of certain neighborhoods would be improved to make them significantly more desirable for living and business development. In many ways, this goal was accomplished. However, as is the case with many initiatives rooted in economic benefits, one must then ask who, exactly, will be experiencing these benefits? The answer to this question has spurred debate about fair housing laws for decades.1Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.95

Though it is difficult to pinpoint the start of inequitable housing practices in Rhode Island, a 1942 incident in Newport, Rhode Island is a crucial moment. At a newly built military housing area on Tonomy Hill, upon completion of the housing project, one hundred White residents in the area signed and delivered a petition to Newport Mayor McCauley “expressing concern the project had recently opened rentals to Negros.” Their petition included five points justifying their objection:

1. The unusual close association of white and colored children.

2. The noticeable difference in general standard of living between white and colored races.

3. According to recent health statistics, a marked difference between health and sanitary conditions existing between the two races.

4. The presence of major handicap in social affairs of the project.

5. The maintenance of the morale and prestige of the white race which in these critical times we believe are worth more than a few advantages conferred at the Tonomy Hill Housing Project affairs.”2Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p.13-14

The racist attitudes displayed above were extremely common in that time and held a firm grip on most of society, especially in the arena of housing practices. In the following years, those who held these racist ideals created a vehicle to further impose discriminatory housing in Rhode Island with the passing of the Community Redevelopment Act of 1946. This act allowed for the formation of the Providence Redevelopment Agency (PRA), an entity that would evolve throughout the years and serve as a primary instrument to enact urban renewal projects. A prime example of this came in 1950 when the Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Act was passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly. This act provided the PRA with the right to acquire private homes and properties in blighted areas by eminent domain.3Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.90-91

The legality of the Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Act was tested for the first time in 1952 when a man named George Ajootian took court action to stop the city from taking his property. Ajootian owned a two-family house and two lots of land on South Street, located in the Point Street project area, and his property was scheduled to be taken by eminent domain. In Ajootian v. Providence Redevelopment Agency, the Rhode Island Supreme Court got its first opportunity to determine if the PRA had properly identified the Point Street area as blighted as defined by the Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Act.4Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.91 The area is described in the transcripts of the court proceedings as “streets [that are] narrow and congested” and that of the “125 dwelling units which are contained in 49 structures and are occupied by about 400 people…71 percent have no central heating; 63 percent have no inside hot water; 62 have no private bath…85 percent have serious deterioration.” It was also “further alleged that because of such conditions, the incidence of juvenile delinquency, aid to dependent children, tuberculosis and other diseases are disproportionately high.”5Supreme Court of Rhode Island. “Ajootian v. Providence Redevelopment Agency.” 11 Aug. 1952. Justia US Law This certainly paints a grim picture, and it was decided that the Point Street area was correctly identified as blighted and thus subject to eminent domain. This meant that George Ajootian could not stop the city from taking his property.

This significant court ruling was followed by the proposal of Amendment XXXIII to the Rhode Island Constitution in 1955. The amendment sought to establish the constitutionality of redevelopment and was eventually ratified by voters through a question at the ballot booth. It stated that “The clearance, re-planning, redevelopment, rehabilitation, and improvement of blighted and substandard areas shall be a public use and service for which the power of eminent domain may be exercised…”6Patrick T. Conley and Robert G. Flanders, Jr. “The Rhode Island Constitution: A Reference Guide.” Reference Guides to the State Constitutions of the United States. Westport, CT. Praeger Publishers. 1955. p.199 What this means is that there was now an amendment that gave the city the power to take ownership of property and land that was in “disrepair” for the purpose of redevelopment that would benefit the public at large. In 1956, the General Assembly passed legislation that created redevelopment agencies with authorization for conservation and rehabilitation in each city and town in Rhode Island.7Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.93 And thus, the framework and authority of urban renewal and redevelopment projects in Rhode Island was established and a precedent was set for a practice that would be replicated and expanded throughout the following decades.

The first official urban renewal project to be started in Providence was the Willard Center Redevelopment in 1954. The pilot project took place in an 18-acre stretch of land located on Prairie and Willard Avenue. This was a commercial area in South Providence and a place where business was noticeably on the decline. It was also a place where many, mostly minority, families lived. Upon the completion of the project, the tenement houses and dilapidated commercial buildings were replaced by a new shopping center, Flynn Elementary School, and a park. Many of the businesses were able to set up shop in the newly built shopping center, but the nearly 200 families who lost their homes were forced to relocate to nearby neighborhoods.8Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.93-104 This would be a trend that would continue with future urban renewal projects around the state. The business environment was arguably improved by the project, and with the removal of junkyards and other forms of dilapidation, the living conditions in the area were also dramatically improved. However, with no official plan in place for the relocation of the families that were displaced by the project, the result was increased home values that often could only be afforded by more wealthy and mostly White families. This is how urban renewal projects not only change the buildings of a neighborhood, but also the lives of the people who live there, by eradicating communities that are based upon physical proximity.

A more jarring and blatant example of this strategy by city officials occurred five years later, in 1959, with the Lippitt Hill Redevelopment Project. Lippitt Hill is a 30-acre area situated on the East Side of Providence (roughly) bounded by North Main, Olney and Camp Streets and Doyle Avenue, and only a few blocks away from Benefit Street. It was also one of the oldest African American communities in the state. In the years prior to 1959, various urban renewal projects on the East Side, particularly on Benefit Street, had been blocked on the basis of historical preservation by the newly formed Providence Preservation Society and the strong neighborhood committees throughout this part of the city. Unfortunately, the residents of Lippitt Hill lacked the clout and power of their affluent College Hill neighbors and they were unable to prevent the demolition of their neighborhood. By November 1959, the entire neighborhood was officially condemned by the PRA and was transferred to city ownership. Lippitt Hill homeowners were forced to take cash settlements for their properties and renters were given stipends to assist with move-out costs. Upon the completion of an Official Redevelopment Plan, a court-approved “slum clearance” could begin.9“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of freedom, 2017 [link]

An important feature of the Lippitt Hill project is that although the demolition and slum clearance were performed by the city, the redevelopment component of the project was open for bidding from private firms. The winning bidder was University Heights Inc., led by Providence businessman Irving Fain. For this reason, the project is often referred to as the University Heights Project. Irving Fain was a man who was passionate about racial equality and had organized Citizens United for a Fair Housing Law as a way to campaign for legislation that would prohibit discrimination in private and public housing.10Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p18 He attempted to realize this mission through University Heights and even addressed the issue of the inevitable displacement of the minority communities in the Lippitt Hill neighborhood in the bid proposal:

“It is their [the developer’s] determination that University Heights will become a wholesome, desirable area of Providence, outstanding not only for its environmental advantages but…as a demonstration to Providence and to America that people of many backgrounds can live in harmony.”11University Heights: A Proposal for Lippitt Hill, 1962. p4

This idealized final product of racial harmony would consist of “a complex of 482 middle- to high-income apartments and [an] adjoining University market place.”12Ben Berke. “Providence’s Lippitt Hill Residents Get a Chance to Tell Their Story.” Providence Journal, 2017 It was implied that many of the displaced families would be able to find affordable housing in the new apartment complex, and further, that “The exterior design of the low-income blocks was such that this status was indistinguishable from the higher income units.”13“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of Freedom, 2017 [link]

Despite what appears to have been due consideration for the displaced community, the results of the project tell a much different story. A total of 650 dwelling units were demolished, and 450 of them were occupied by non-White tenants. Many of these former tenants would go on to face extreme discrimination when they tried to rent new housing because many landlords would not rent to African Americans. This form of racism was the status quo in a 1960 housing market that was legally discriminatory.14Ben Berke. “Providence’s Lippitt Hill Residents Get a Chance to Tell Their Story.” Providence Journal, 2017

Today, the University Heights apartment complex still stands on the site of what was once the Lippitt Hill neighborhood. It is accompanied by a large shopping center that houses a Whole Foods, Starbucks, and McDonalds (among other businesses). In addition to racial harmony and diversity, another promise of Irving Fain and University Heights, Inc. was that there would always be at least one black-owned business within that shopping center. Mr. Fain would undoubtedly be upset to learn that as of 2020, there is not a single black-owned business in the complex. However, the financial success of the venture cannot be denied, as the shopping center serves as a main center of commerce for the entire East Side and beyond.

An interesting detail from the Lippitt Hill/University Heights case is the role that local preservationist Antoinette Downing played in it. She is famous for founding the Providence Preservation Society, which led to the preservation movement that saved many of the historic homes and neighborhoods on the East Side from being demolished. She also served on the board of University Heights, Inc., which made her heavily involved in the redevelopment of Lippitt Hill.15“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of freedom, 2017, [link] This connection makes it clear that “preservation” was a priority for the “white neighborhoods” of the East Side while the preservation of the “black neighborhood” was ultimately less important than the need for a new supermarket. It is precisely these realities that, in 1966, led the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Floyd B. McKissick to state that urban renewal in Providence was more appropriately described as “negro removal.”16Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.101 The urban renewal projects of Providence seemed to have accomplished the exact goal of those who had signed the petition in Tonomy Hill two decades earlier.

Between the years of 1940 and 1960, the African American population in Providence increased from 6,388 to 11,900. By 1965, eighty percent of this population was forced to move at least once due to urban renewal projects.17Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74 (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. 95 Well aware of these facts, the city and state attempted to address this inequity and around this time Joseph Doorley took over as mayor of Providence (1965). Even in those days, it was understood that urban renewal was having a disproportionately negative impact on communities of color. What was also well understood was that many of the neighborhoods in question truly were in disrepair and, without a doubt, needed to be rehabilitated. Mayor Doorley believed that he could find a solution wherein he could eliminate slum areas without having to displace people. His commitment to integrate a “social renewal as well as a physical renewal” conveyed the understanding that urban blight is as much a product of poor social conditions as it is deteriorating buildings. In order to address this, Doorley worked to build enthusiasm for his urban renewal projects among the citizens with the idea that urban renewal was something everyone benefited from. His many press releases and the national attention he received for his efforts created an image of commitment to this optimistic message.18Carl Antonucci, Carl. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.97-102 Unfortunately, as was the pattern, good intentions did not always result in good outcomes.

In 1965, the “Rhode Island Fair Housing Practices” law was enacted with the goal of eradicating the legal discriminatory practices minorities faced in the housing market. The opposition to fair housing laws was fierce. In the years prior, 500 opponents to fair housing led by Providence attorney Robert Dresser protested at the Rhode Island State House, stating that “a fair housing law would infringe on private property rights, legislate social progress, lower property values and increase racial tension in the state.”19Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle For African American Civil Rights In 20th Century Rhode Island A Narrative Summary of People, Places & Events. p.15-16 These complaints echo the same opinions displayed over 20 years earlier in the petition at Tonomy Hill in Newport.

Racial tensions in private and public housing continue to be a problem in the United States as well as in Rhode Island. Through historical research, we can better understand the ways that the state and federal governments participated in discriminatory housing practices and also the ways that they tried to, successfully and unsuccessfully, remedy that very problem. The fact that many solutions were pursued in good faith and yet still failed to resolve these issues is proof of how complicated urban renewal was (and still is) as a practice. Most of the structures built during the urban renewal boom can still be seen today. It is undeniable that many of these projects have been very successful in bringing increased traffic and revenue into the city. In some ways, this justifies the initiatives. However, there are those who continue to remind us of the neighborhoods that once stood in these places of the communities that were displaced, and of the promises that were left unfulfilled. The racial discrimination operative in the cases of Tonomy Hill in 1942 and of Robert Dresser in 1963 absolutely still exists. Opposition by residents and some lawmakers against having low-income housing built in certain neighborhoods use similar arguments – racist opinions cloaked in economic rationales – that low-income housing brings higher crime with it and lowers the sale-ability of surrounding homes. Perhaps this is what Mayor Joseph Doorley meant when he advocated for a “social renewal” that must occur if “urban renewal” is ever to be successful.

Terms:

Urban Renewal: a program of land redevelopment often used to address urban decay in cities

Urban Decay: the process by which a previously functioning city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair

Racial Inequality: a disparity in opportunity and treatment that occurs as a result of someone’s race

Dilapidation: falling into disrepair

Fair Housing Laws: laws that protect people from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home, getting a mortgage, seeking housing assistance, or other housing-related activities

Inequitable: unfair or unjust

Negros: a term used to describe people of African descent or with dark-colored skin. During the Civil Rights Movement, this word was used often whereas it is now considered disrespectful. However, some people still self-identify with this term. You may also come across the terms African American, Black, person of color, colored person, or colored. Colored person and colored are also outdated terms

Providence Redevelopment Agency (PRA): an agency in Providence that uses the power of land acquisition to create urban renewal projects that address urban decay and promote economic development in struggling areas of the city

Blighted: a decrease in value of an area caused by ageing, neglect, deterioration, and a lack of financial support for maintenance

Eminent Domain: the right of a government to take ownership of land for public use

Constitutionality: the condition by which an action follows a law set forth by a constitution

Displaced: force someone to leave their home

Clout: influence or power

Affluent: having a great deal of money; wealthy

Slum Clearance: an urban renewal strategy used to transform low income settlements with a poor reputation into another type of development or housing.

Citizens United for Fair Housing Law: a group of local citizens who organized to push for laws and politics that promote fair housing

Legally Discriminatory: acts of prejudice, bigotry, discrimination, and segregation that are not prohibited by law

Questions:

What are some of the benefits of Urban Renewal? What are some of the negatives?

Why did many people of color have a hard time finding places to live in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s?

What does fair housing mean and why is it important?

- 1Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.95

- 2Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p.13-14

- 3Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.90-91

- 4Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.91

- 5Supreme Court of Rhode Island. “Ajootian v. Providence Redevelopment Agency.” 11 Aug. 1952. Justia US Law

- 6Patrick T. Conley and Robert G. Flanders, Jr. “The Rhode Island Constitution: A Reference Guide.” Reference Guides to the State Constitutions of the United States. Westport, CT. Praeger Publishers. 1955. p.199

- 7Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.93

- 8Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.93-104

- 9“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of freedom, 2017 [link]

- 10Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p18

- 11University Heights: A Proposal for Lippitt Hill, 1962. p4

- 12Ben Berke. “Providence’s Lippitt Hill Residents Get a Chance to Tell Their Story.” Providence Journal, 2017

- 13“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of Freedom, 2017 [link]

- 14Ben Berke. “Providence’s Lippitt Hill Residents Get a Chance to Tell Their Story.” Providence Journal, 2017

- 15“LIPPITT HILL PROJECT.” Stages of freedom, 2017, [link]

- 16Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.101

- 17Carl Antonucci. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74 (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. 95

- 18Carl Antonucci, Carl. Machine Politics and Urban Renewal in Providence, Rhode Island: The Era of Mayor Joseph A. Doorley, Jr., 1965-74. (2012). History Dissertations. Paper 1. p.97-102

- 19Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle For African American Civil Rights In 20th Century Rhode Island A Narrative Summary of People, Places & Events. p.15-16