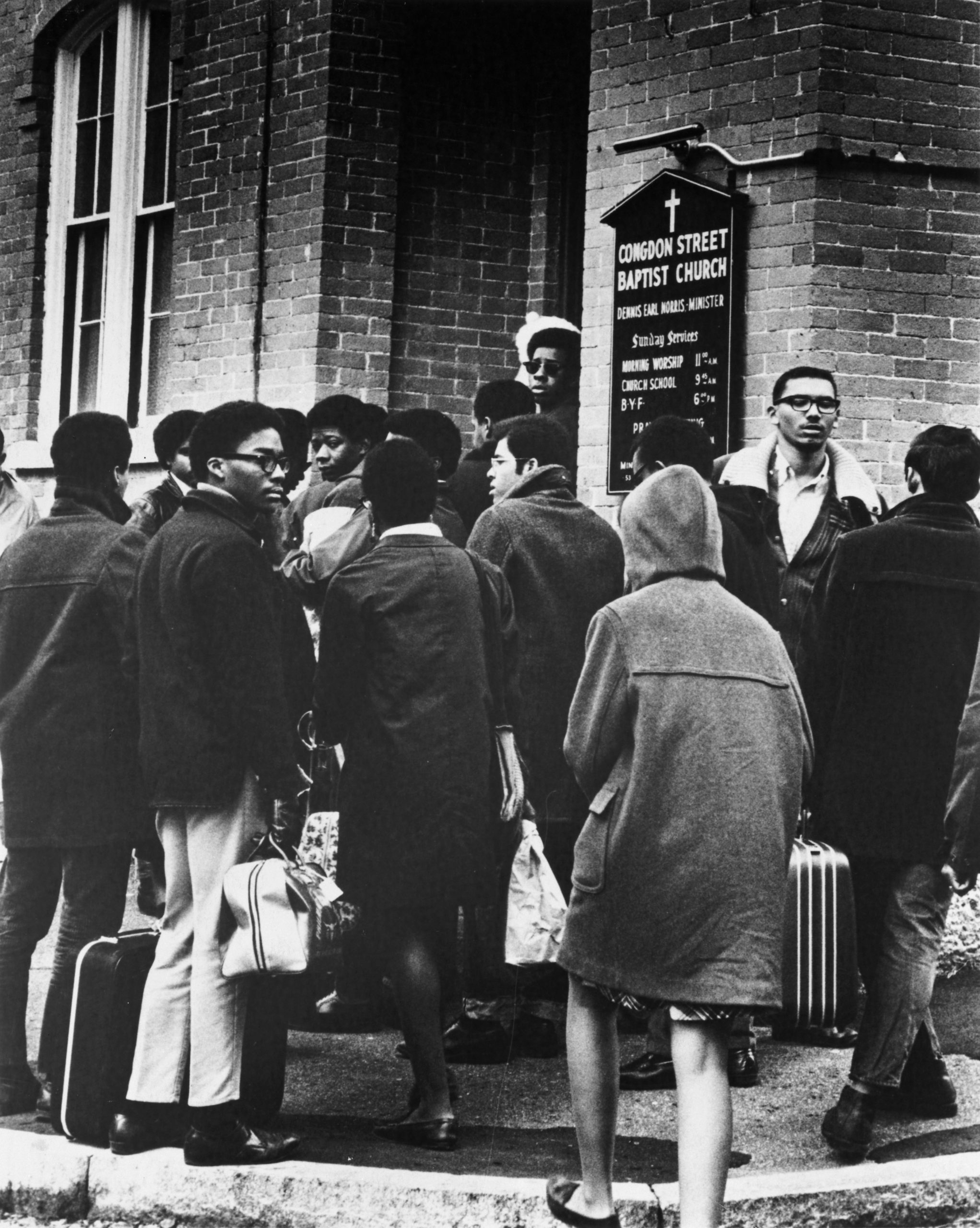

Film Still of Student Clash Outside of Central High

On October 4, 1971, Black and Italian American students clashed with each other at Central High School. Given that this occurred soon after the new school year began, school officials and members of the media speculated it was a result of the Providence Plan. This is a still image taken from video footage.

Civil Rights in Education

Essay by Geralyn Ducady, Director of the Newell D. Goff Center for Education & Public Programs

In 1855, George T. Downing, then a successful Black caterer living in Providence, began a years-long campaign to desegregate Rhode Island’s schools after his children were refused admission to the schools in Newport. Following in the footsteps of their neighbors to the North, Black Rhode Islanders like Downing saw the integration of schools in Massachusetts as a call to action in their own state.1Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.154 Facing racism despite his economic status, Downing was a leader in early civil rights activities. In 1866, after eleven years of effort by Downing, the Rhode Island legislature finally made it illegal for cities and towns to segregate their schools.2Lawrence Grossman. “George T. Downing and Desegregation of Rhode Island Public Schools. 1855-1866.” Rhode Island History 36, no. 4 (November 1977): 99-105 [link] Nevertheless, de facto segregation still occurred. Due to racist employment practices, like companies refusing to hire non-White employees, many people of color faced difficulty obtaining higher-paying professional jobs. This led to a disproportionate number of people of color with lower earning power. This, along with discriminatory housing practices, led to highly segregated neighborhoods and, thus, segregated neighborhood schools. What this means is that though schools were not allowed to turn away students because of their race, since neighborhoods were segregated, most schools remained segregated.3Kelton Ellis. With illustrations by Dorothy Windham. “Small State, Big Gaps: Segregation in Rhode Island’s Public Schools.” The Indy, November 4, 2016

These conditions persisted into the 20th century. After World War II, many White families fled urban areas and moved into the suburbs. A commonly used term for this is “White flight,” and it occurred throughout the United States. Rhode Island was neither an exception nor was it unusual in this regard. Individuals with higher earning power generally moved to the suburbs. Lower-income residents were not able to keep up the maintenance of homes, property values dropped, and property taxes subsequently also dropped. Since taxes help to fund public schools, this further eroded the economic support of urban schools in segregated neighborhoods with lower home values. This led to further segregation and to unequally-funded school districts. “Due to the property tax funding model, a school’s resources tend to reflect those of its student body and surrounding neighborhoods. Schools that are poorer, which are invariably attended by mostly students of color, suffer from lower achievement due to this disparity.”4Kelton Ellis. With illustrations by Dorothy Windham. “Small State, Big Gaps: Segregation in Rhode Island’s Public Schools.” The Indy, November 4, 20165Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974:135-136

How did Providence’s students react to separate and unequal schools? On May 9, 1969, between 150 and 200 Black students staged a walkout at Hope High School after their principal, Max H. Faxman, refused to discuss a list of complaints they had prepared. Students had a meeting with school officials the next day. However, that came to an end when they could not agree on resolutions over some of the issues. On May 13, students damaged school property in protest (reported in the media as a “rampage”) after the negotiations stopped. What were the students requesting? Students reported that some of their teachers were racist, noting that different tests were given to Black and White students and giving an example of a teacher commenting on a Black student’s hair to make the White students laugh at him. “I came to school this year with natural hair. My teacher had some remarks with me. I didn’t have to take that, but I did. All the white cats laughed.”6C. Fraser Smith. “Black Hope Students List Aims.” Providence Journal, May 15, 1969. p.25

Because of issues like these, the students wanted their teachers held accountable. Students also wanted more teachers and school administrators of color working at their school. More teachers of color would help ensure that students of color felt that they were represented in the school’s authority and leadership and that they had a safe place to talk about issues they had or the help they needed. Students also noted that the history curriculum focused on White heroes and stories. Neither Blacks nor other groups of color were represented in the curriculum, and students called for a course in Black history and literature.7C. Fraser Smith. “Black Hope Students List Aims.” Providence Journal, May 15, 1969 p.25

The Hope High School protests may have been inspired by protests at Brown University six months prior. On December 5, 1968, 75% of Brown University students of color staged a “walk-out” in protest of unequal representation on campus. At the time, African Americans made up 11% of the overall population in the United States but only 2.3% of Brown’s population. Students advocated for policies that would ensure a higher and proportionate percentage of students of color on campus. In addition, students who walked out asked for a similar list of demands to the students at Hope High School. Brown University students also wanted more professors, administrators, admissions officers, and staff of color.8The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019. p.21-22 In addition, they wanted an African American Studies major to be developed with several courses in African American history and current events. Some, but not all, of the demands were met. The Africana Studies Department was founded, but students voiced concern over issues such as recruitment again in 1975 and, more recently, in 2015. In that year, the University established a Diversity and Inclusion Action.9WGBH News. “Fifty Years Ago, Black Students Walked Out for Change.” December 5, 2018. [link]

In the early 1970s, President Nixon identified school segregation as an issue in cities across the country.10New York Times. “Text of the President’s Statement Explaining His Policy on School Desegregation.” March 25, 1970, p. 26. Accessed July 16, 2020 [link] Lawmakers also argued that racism persisted because children were not exposed to each other due to segregated schools. An NAACP field agent threatened Providence with a lawsuit if they did not initiate a plan to desegregate the city’s public schools.11Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.170 In an attempt to solve this issue, cities across the north, including in Rhode Island, implemented plans to integrate the schools. Most plans centered around the busing of children, discussed below, and some went hand-in-hand with urban renewal projects.12For more information about urban renewal, please see our Encompass essay [link] Providence Mayor Joseph A. Doorley put forth The Providence Plan.13Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p.17-18; The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019. p.21

The Providence Plan consisted of closing two schools, Flynn Elementary School and Temple Elementary School, and busing children to schools outside of their neighborhoods in an attempt to diversify all schools and encourage students from different neighborhoods to interact with one another. Examples of schools whose student population were made up of mostly Black students include the Doyle Elementary School (97%) and Jenkins Elementary (95%) in 1967. In some cases, children were bused to other schools across the city, far away from their own neighborhoods. Some school administrators and parents agreed with the plan and believed that by diversifying the schools, all children would have a better education. They thought that children, no matter their race, should have equal educational access. These individuals also thought that children would learn from one another about the lived experiences of students who came from diverse racial, class, and religious backgrounds since they would be learning together. Yet, the parents of Providence’s schoolchildren had their reservations about these plans. Some Black parents believed that it was mostly their children who were being bused out of their neighborhoods and thought the new policy unequally affected their children. And, indeed, this may have been true. The part of the Providence Plan affecting the elementary schools projected that 76% of the children to be transferred to new schools were Black.14Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.193 Some Black parents noted that if a child was sick and needed to be sent home, it could be difficult for a parent who did not have their own vehicle and who was reliant on public transportation to travel to the school to pick up the sick child. Some parents believed the sense of the neighborhood community would be broken if kids were not attending neighborhood schools. All of these concerns and beliefs were valid, and the program was implemented without much public support.15Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974

Providence’s high schools were integrated according to the Plan by the start of the school year in 1971. Students from the predominantly White Italian neighborhood of Federal Hill and students from the predominantly Black neighborhood of South Providence attended Central High School together. In early October, racially charged student altercations forced the school to close for a week. Officials disagreed with each other about whether the new Providence Plan contributed to the racial tensions that led to the student conflict. White students complained that Black students assaulted them and took their money, while Black students complained that White students at the school received preferential treatment and that the courses at the school were irrelevant to them.16Dante Ionata. “Racial Conflict Closes Down Central High.” Providence Journal, October 5, 1971

Did the Providence Plan work? According to researcher Anna Holden who interviewed teachers, parents, and administrators in 1973, “Providence’s school desegregation plan was effective in almost completely eliminating school and classroom segregation from the city’s elementary schools.”17Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.274 However, it certainly did not remain that way over time. A 2015 article in the Providence Journal points to continually high rates of segregation in Rhode Island’s schools. The article’s authors claim Rhode Island had the sixth most segregated schools in the United States at the time of its writing. They also note that 20% of all of Rhode Island’s public schools are 90% White, while in 14% of the public schools, 90% are students of color. These statistics demonstrate that racial segregation in Rhode Island public schools is still a very real issue today.

While school segregation in the mid-1900s primarily pertained to Black and White students, more recently Latinx students experience “language segregation” as well as racial and economic segregation.18Linda Borg, Patrick Anderson, and Paul Edward Parker. “Separate and Unequal: Racial Segregation Widespread in R.I. Public Schools.” Providence Journal, November 8, 2015. p.1 A 2019 report from Johns Hopkins University specifically pointed out several issues with Providence’s schools, including a lack of quality curriculum, poor test scores, and high schoolers not being aptly prepared for college courses. Latinx parents, who represent the majority of the population, feel marginalized, and students and teachers do not feel safe. Many of these issues stem from racial inequality.19Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy. Providence Public School District in Review. June 2019

The actions and requests of high school and college students of the 1960s and 1970s at Hope, Central, and Brown reflect what happened at other schools throughout the state and nation. We still see patterns of segregation within our cities and towns, and students continue to fight for change. In the early 2000s, students at Hope High School formed a group called Hope United that staged a walkout in an effort to change the curriculum to better reflect stories of people of color. Similar student organizations were formed at other Providence High Schools, including Central High. The organizations merged in 2010 to form the Providence Student Union (PSU). PSU tackles all sorts of issues important to Providence’s diverse student population, many of which reflect those of the Civil Rights era. Students successfully asked for an Ethnic Studies course with a curriculum inclusive of the histories and cultures of the student population. A 2019 Providence Journal article contained interviews of the students themselves. Many of the students noted that some actions by the predominately White teaching staff have left them feeling “uncomfortable, stereotyped, and belittled by their teachers.” Student Aleita Cook noted an incident where a teacher “thought my Afro was a wig….I’m like ‘It’s my natural hair’” echoing a student’s complaint from 1969. The students proposed a solution to this problem—the school department should recruit more teachers of color. In addition, that all teachers, regardless of color, should be trained in cultural competency, or the ability to understand and interact with people, in this case students, across cultural backgrounds.20Madeleine List. “Providence Students Say Race is a Big Part of Disconnect with Teachers.” Providence Journal, August 16, 2019. [link]21Providence Student Union [link]

The students’ actions have inspired advocacy from other groups, for example, a recent push by the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society to require African American history in the school curriculum throughout the state.22Sean Flynn. “Newport City Council backs African Heritage courses for all schools in state.” Newport Daily News, July 24, 2020 The 1696 Historical Commission was established in 2014 to develop African American history curriculum in Rhode Island, and indications are that it will succeed.23Office of the Secretary of State. Report of the 1696 Historical Commission. State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. August 1, 2015. (Report 1 and Report 2)

Terms:

De jure segregation: refers to the separation of races in schools, neighborhoods, employment, and elsewhere “by law.,” meaning that there are laws that prohibit Blacks and Whites from socializing or being in these same spaces

De facto segregation: refers to the separation of races in schools, neighborhoods, employment, and elsewhere “by fact.” It is compared to “de Jure” segregation since it does not occur because it is the law, but because of other societal forces

People of color: a term used to describe people who are not considered or who do not identify as White

Property tax: money collected by local town/city municipalities based on a percentage of the value of a person’s home or land within that town/city used to pay for common services such as schools, police, fire, and the maintenance of roads, etc.

Integrate: to bring together

Latinx: a person of Latin American origin or descent

Language segregation: treating or separating those who speak a language other than English. This can lead to unequal education if teachers or administrators fail to recognize a student’s ability in school subjects because of a language barrier

Marginalized: a person or group with less access to power, decision-making and influence. That person or group may also be forced into homes and jobs that are less desirable or more dangerous

Questions:

Why is it important for students of color to have teachers, administrators, and staff at their schools who come from similar racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds? Do you see teachers, administrators, and staff who “look like you” at your school? Why do you think it is the case that they do or do not? How does that affect your learning and social experience at school?

Why do people believe that integrated schools make for a better school experience? What do you believe and why?

In what ways do you think you can push for change at your school? Are there issues you would like to address at your school?

- 1Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.154

- 2Lawrence Grossman. “George T. Downing and Desegregation of Rhode Island Public Schools. 1855-1866.” Rhode Island History 36, no. 4 (November 1977): 99-105 [link]

- 3Kelton Ellis. With illustrations by Dorothy Windham. “Small State, Big Gaps: Segregation in Rhode Island’s Public Schools.” The Indy, November 4, 2016

- 4Kelton Ellis. With illustrations by Dorothy Windham. “Small State, Big Gaps: Segregation in Rhode Island’s Public Schools.” The Indy, November 4, 2016

- 5Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974:135-136

- 6C. Fraser Smith. “Black Hope Students List Aims.” Providence Journal, May 15, 1969. p.25

- 7C. Fraser Smith. “Black Hope Students List Aims.” Providence Journal, May 15, 1969 p.25

- 8The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019. p.21-22

- 9WGBH News. “Fifty Years Ago, Black Students Walked Out for Change.” December 5, 2018. [link]

- 10New York Times. “Text of the President’s Statement Explaining His Policy on School Desegregation.” March 25, 1970, p. 26. Accessed July 16, 2020 [link]

- 11Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.170

- 12For more information about urban renewal, please see our Encompass essay [link]

- 13Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. The Struggle for African American Civil Rights in 20th Century Rhode Island: A Narrative Summary of People, Places, and Events. Report for the National Park Service. Providence. 2018. p.17-18; The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Survey Report African American Struggle for Civil Rights in Rhode Island: The Twentieth Century: Statewide Survey and National Register Evaluation. Report submitted to the Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission for the National Park Service. Providence. 2019. p.21

- 14Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.193

- 15Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974

- 16Dante Ionata. “Racial Conflict Closes Down Central High.” Providence Journal, October 5, 1971

- 17Anna Holden. The Bus Stops Here: A Study of School Desegregation in Three Cities. Bronx: Agathon Press. 1974. p.274

- 18Linda Borg, Patrick Anderson, and Paul Edward Parker. “Separate and Unequal: Racial Segregation Widespread in R.I. Public Schools.” Providence Journal, November 8, 2015. p.1

- 19Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy. Providence Public School District in Review. June 2019

- 20Madeleine List. “Providence Students Say Race is a Big Part of Disconnect with Teachers.” Providence Journal, August 16, 2019. [link]

- 21Providence Student Union [link]

- 22Sean Flynn. “Newport City Council backs African Heritage courses for all schools in state.” Newport Daily News, July 24, 2020

- 23