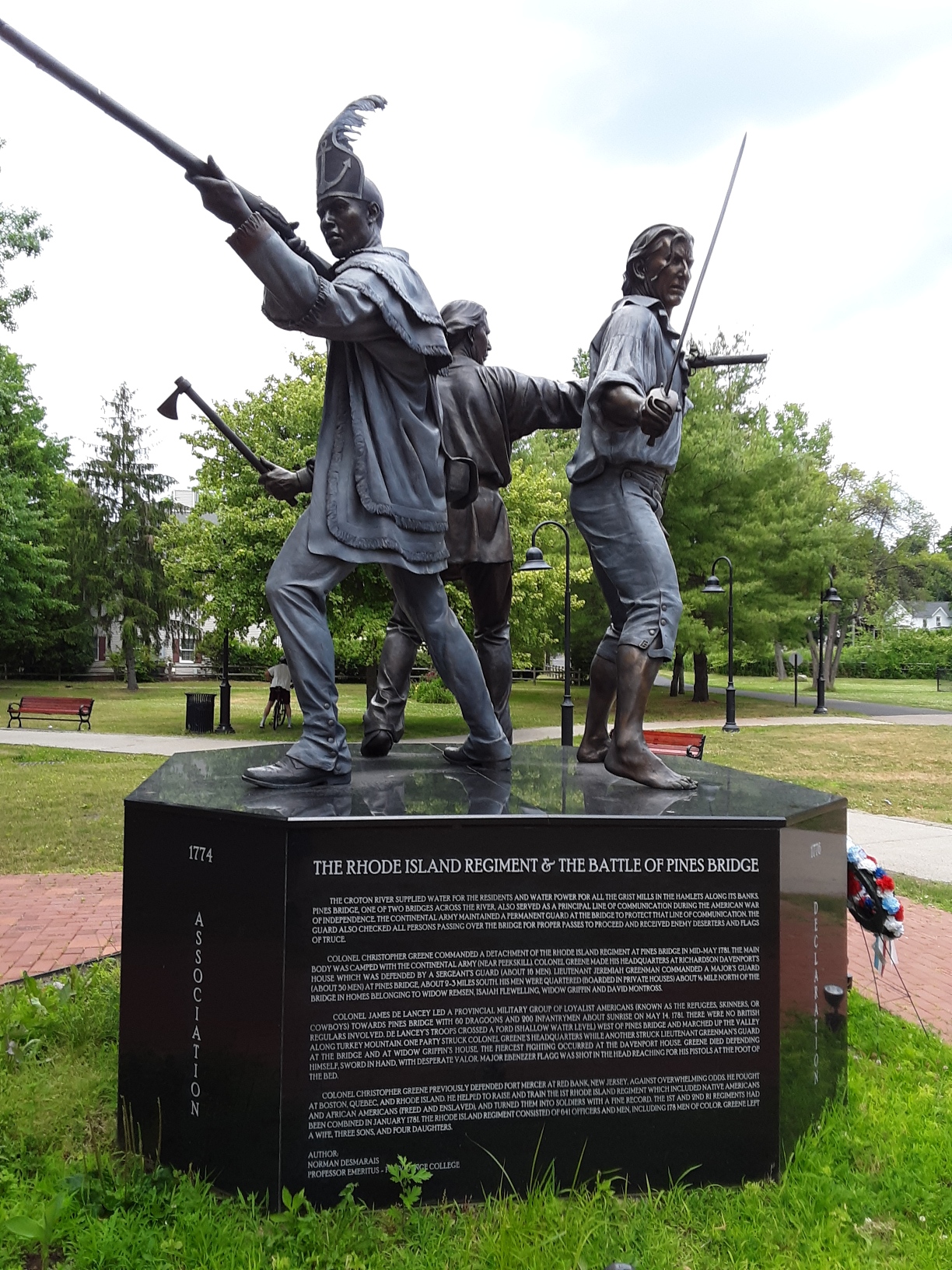

The Battle of Pines Bridge Monument

There’s a striking monument dedicated to the soldiers of the First Rhode Island Regiment in Yorktown Heights, New York. Not far from the site, the regiment was surprised just after dawn on May 14, 1781 by a large party of Loyalists resulting in the death of the white commander, Christopher Greene along with several of his men. The engagement was a complete success for the enemy, so why was this monument dedicated to the regiment?

The First Rhode Island was unique because it was the first time a state recruited enslaved Black and Indigenous men to fight in the Continental Army. Along with other free men, “the monument is designed to reflect that diversity, and will be the first revolutionary War memorial to depict all three races together in combat.”1“The Pines Bridge Monument” [link]

The white officer, an Indigenous man, and a Black man are depicted as being prepared to engage the enemy. They look determined to fight, all facing out with their backs protected by their comrades, implying trust, brotherhood, and equality.

The First Rhode Island Regiment

Essay by H. Scott Alexander, Historian

When war began after Lexington and Concord in 1775, many Rhode Islanders answered the call to fight. When George Washington took command, the Rhode Island militia units became part of the newly organized national army, the Continental Army. For two and a half years, they fought in most of the northern battlefields in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

The origin of what would be called the “Black” regiment began at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, during the winter of 1777-1778. Severe shortages of troops had weakened the entire army. This was caused not only by desertions and casualties inflicted by combat or disease but also owing to the relatively short period of enlistment. Many signed up for between a few months up to about a year. A bold proposal forwarded by General James Varnum of Rhode Island to Commander George Washington tried to address this problem by enrolling new recruits for the duration of the war with a radical and innovative twist.2Robert A. Geake & Loren M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution, Westholme Publishing, 2016, p. 20 There were two Rhode Island regiments in the encampment with a shortage of men. Varnum suggested combining all of the enlisted men into one unit, the Second Rhode Island, and sending the officers of the First back to their state to replenish its ranks. The radical part of the proposal was to enlist a regiment consisting entirely of enslaved men. The governor of Rhode Island thought that at least 300 could be gathered in this way.3“Governor Cooke to George Washington, February 23, 1778” Rhode Island State Archives, Digital Collection, African-American Collection Since the war’s duration seemed to be discouraging men from enlisting even with attractive rewards like money up front and old age pensions, the desire of enslaved men for their freedom might prove to be a compelling incentive.

It would also counter the embarrassing situation of so many enslaved people, especially in the South, flocking to the British lines. Americans called these self-liberating individuals runaways. No matter what they were called, it was obvious that the desire for freedom was overwhelming. During the Revolution, it has been estimated that over 20,000 enslaved people took an active role in the combating armies, with 75% (15,000) on the British side.4Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, New York University Press, 2016, p.70 This was one way to stop that flow of manpower to the enemy.

Blacks, both enslaved and free, had been fighting on the American side since the beginning of the war in 1775 at Lexington & Concord. Scholars estimate that there were at least 31 free Black and Indigenous men in the Rhode Island units in 1775 and 750 serving in the militia and Continental Army ranks for the state during the entire war.5“The Battle of Rhode Island” The Rhode Island Society of the Sons of Liberty. 2006 When Washington arrived outside of Boston to assume the command of the Continental Army, he was “… alarmed to find so many armed African Americans…and forbade black men to enlist…”.6Robert A. Geake and Loren M. Spears.From Slaves To Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution. Yardley, PA, Westholme Publishing LLC. 2016.p. 21 However, it would not take long for this to be ignored as the Americans were constantly struggling for more troops. Though the numbers may never be verified, it has been estimated that there were close to 800 Black men among the ranks of the entire army when Varnum pitched his idea.7John U. Rees, “‘They Were Good Soldiers’: African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783”, Helion & Company, 2019, p. 36

The proposal was forwarded to the governor of Rhode Island, who sent it to the legislative branch for consideration. It did not take long for the General Assembly to cobble together an act that took effect on February 14, 1778. The new law permitted “… every able-bodied Negro, Mulatto and Indian Man Slave…” to enlist and upon passing muster by the officers would be given a paper to present to their enslavers that they had been approved for service and upon completion of the war would be forever free.8Rhode Island State Archives, C#0210-Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly. v. 17, no. 4

In addition, they would be entitled to the same benefits offered to any other recruit, such as signing bounties, monthly pay, and pensions. There would be a committee of five men from the State to compensate the owners of the indentured and enslaved servants by affixing an amount that would not exceed 120 pounds, which was equal to $400 Continental dollars.9“Letter regarding inadequate pay for slaves in Colonel Greene’s regiment, September 3, 1779”, Rhode Island State Archives, Digital Collection, African-American Collection The wording of the law could cause problems for the enslavers and render them quite powerless. An enslaved man who was determined to gain his freedom could take charge of his own fate. The enslaved man needed only to “present” himself and pass muster; the enslavers would ultimately be compensated, but they would not be consulted.10Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, p. 72

Word spread quickly, and within two days, three men had been accepted, although many were not pleased with the terms of the new law and lobbied hard to repeal it. Eventually, six enslavers would sign a letter of protest. The arguments put forth included doubts that enough enslaved men could pass muster, that the enslavers would not be satisfied with the amount of compensation, and that the enemy would belittle them for using enslaved men instead of free whites to secure their rights and liberties.11Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, p. 72-73 This last complaint was hypocritical, for several prominent men had been willing to substitute enslaved men for themselves or other family members when the towns were setting their quotas. One Hessian officer had made note of this fact when he wrote in 1777, “The negro can take the field in his master’s place; hence you never see a regiment in which there are not a lot of negroes, and they are well-built, strong, husky fellows among them.”12John U. Rees. “They Were Good Soldiers” African Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783. Warwick, England Helion & Company. 2019. p.29 A recruiting officer noted that an enslaver was trying to frighten recruits from enlistment by saying that they would be used solely for manual labor or used on the front lines as sacrifices in battle and be sold back into slavery if captured.13“Letter from Captain Elijah Lewis to the Speaker of the General Assembly, March 13, 1778.” Rhode Island Digital Archives, African-American Collection

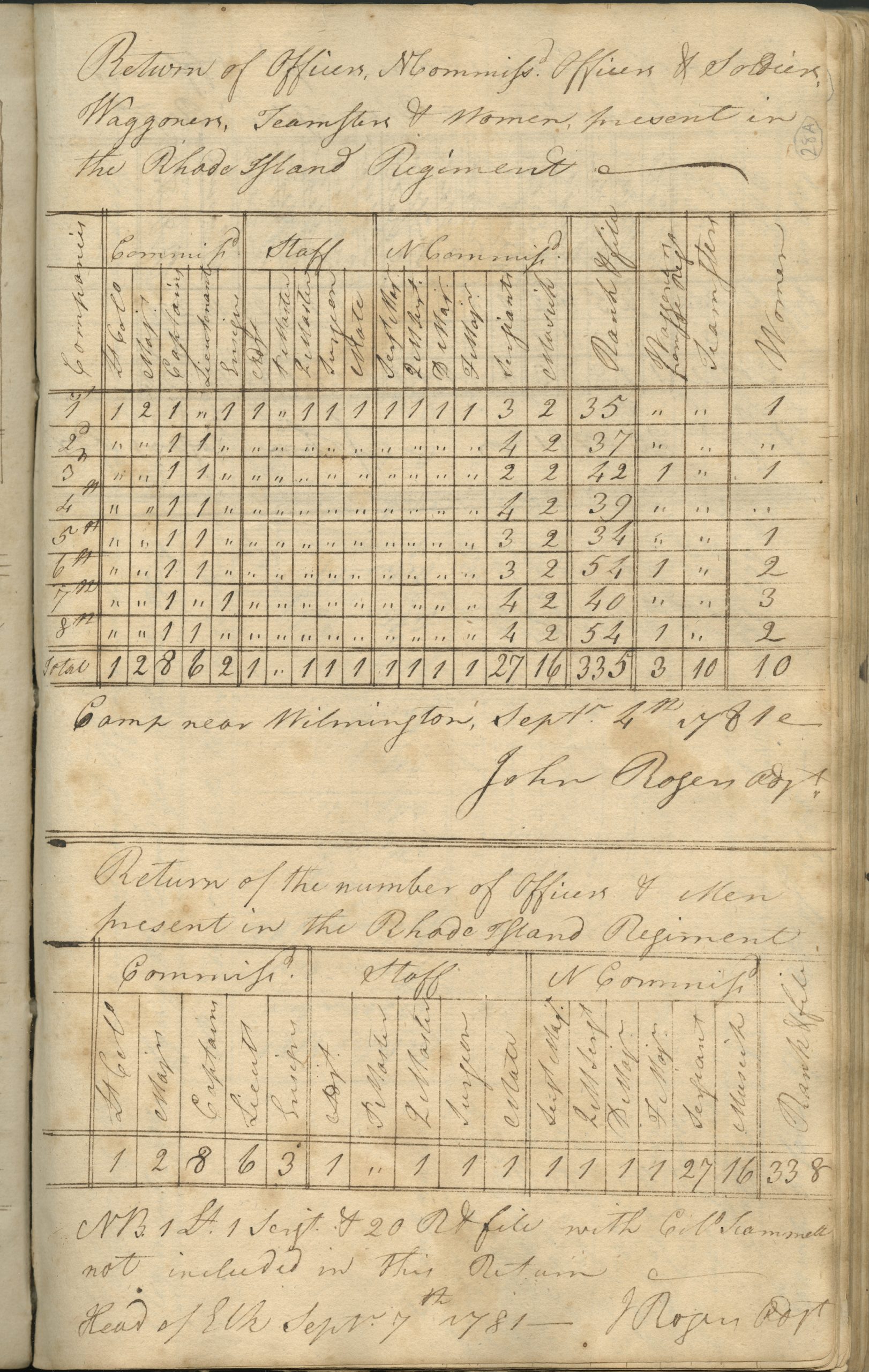

That spring, those who opposed the Act were able to elect new members to the General Assembly who were sympathetic to their complaints. The newly elected officials immediately suspended enrollment of enslaved men by the 10th of June. Within four months, 117 enslaved men had enlisted, and another 44 free men enrolled after the repeal. These newly enrolled recruits served together in small segregated units known as companies. However, the overall regiment was integrated with men who were both enslaved and free.14Rees, “They Were Good Soldiers”, p. 73

The official register of the First Rhode Island listed 225 men, of which 140 were men of color. This included Indigenous men from the local tribes, especially the Narragansetts. For over 100 years, since their defeat in King Philip’s War of 1676, members of the tribe had been enslaved, indentured, or displaced from their traditional villages. Oral tradition states that the men joined for freedom, empowerment, warrior pride, protection of their way of life, and to provide hope for future generations.15Geake & Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers, p. 42-45

As the newly recruited troops trained during the summer, events were placing the spotlight of the war upon Rhode Island. Since December of 1776, the British had occupied Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island. The threat of attacking inland towards Providence and capturing the rest of the state was quite real, and the population was very nervous. The over 400 miles of coastline in Narragansett Bay created a maritime tradition of opportunity for a large proportion of the male population to serve as sailors, for either American warships or the merchant-owned vessels, which turned into privateers. The British warships at Newport acted like a cork in a bottle preventing American ships from leaving the bay. Now it appeared conditions were lining up to “pop” the cork and oust the British for good.

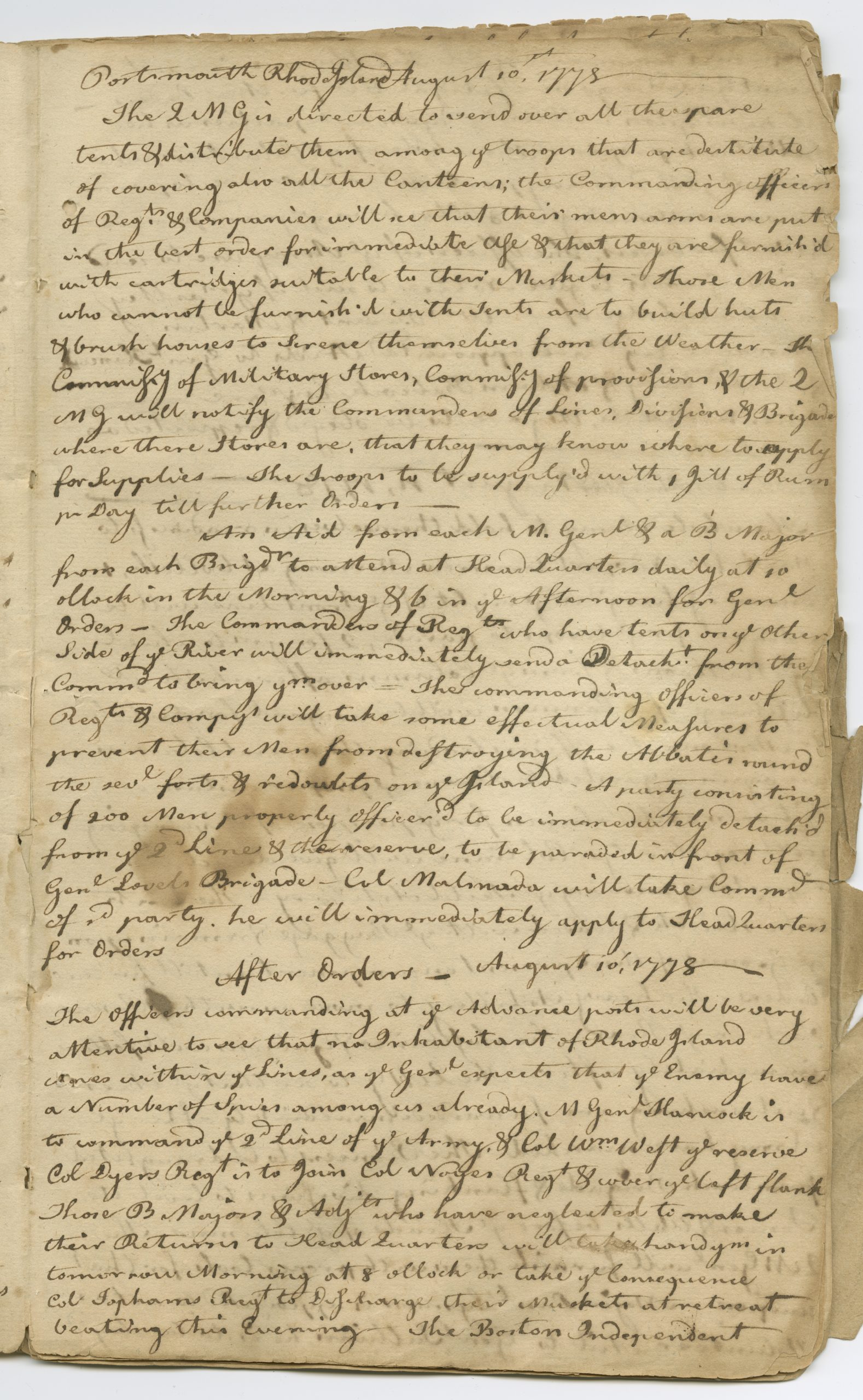

With the major American victory at Saratoga, New York, in October of 1777, the French had changed their secret support into an open alliance with the United States. In the summer of 1778, the French sent a large fleet to help coordinate a joint campaign with the Americans to drive the British from Rhode Island. The opening moves looked promising. However, a hurricane damaged the French vessels, and they departed, leaving the American troops to retreat off Aquidneck Island. The newly formed First Regiment saw their first engagement on August 29th as they were placed on the American right flank in the town of Portsmouth. They stood their ground during three assaults by the Hessian mercenaries hired by the British, and the British attack all along the line failed. Exhausted, the British retreated as the Americans escaped off the Island.16Patrick T Conley, “The Battle of Rhode Island,29 August 1778: A Victory for the Patriots,” Rhode Island History. v. 62, no. 3(Fall 2004), p. 53-58

The “Black Regiment” remained in Rhode Island watching until the British left Newport late in 1779 and then fortified the city during 1780 with French troops. It then joined Washington’s army outside of White Plains, New York. As previously mentioned, the unit suffered a setback in New York in early 1781 with the loss of its commander and several comrades. With the death of Colonel Christopher Greene, the men were led by his replacement, Jeremiah Olney. In a night engagement at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 14, 1781, they captured one of the key defensive positions on the battlefield, prompting the surrender of the British. A French general commented that the First Rhode Island was the best American unit, “…the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in its movements.”17Linda Crotta Brennan, The Black Regiment of the American Revolution, Moon Mountain Publishing, North Kingstown, RI, 2004, p 25

Although the fighting was essentially over, it would take almost two more years for the peace treaty to be signed. The men of the First, having signed on for the duration of the war, spent the remaining time in upstate New York. An ill-conceived winter attack on a British fort on Lake Ontario in 1783 was a disaster, as many soldiers suffered severe frostbite without ever launching an attack. Finally, in June of 1783, most of the men gathered in Saratoga, New York, and were disbanded. Colonel Olney praised them for their “valor and good conduct.” He also regretted that there were no funds from the government to pay them what they were due. When they were dismissed, they all trudged home to pick up their lives.18Ibid, p.26

Most of the formerly enslaved men valued their freedom but soon realized it was not a sufficient benefit on its own for their livelihoods. Their family members were still enslaved and required money for their release. Jobs were scarce, and few whites were willing to hire Black men. Others had been disabled by illness or combat injuries and were not able to care for themselves. In 1785, the General Assembly passed a law making each town accountable for caring for the veterans living in their jurisdiction.19Grundset,Eric G.,ed. Forgotten Patriots: African Americans and American Indians in the Revolutionary War, Washington, D.C.; National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. 2008 However, the towns avoided this obligation by refusing to provide care if they had been born in another town by a system known as “warning out.”20Geake & Spears. From Slaves to Soldiers. p. 98; For more information on Warning Out, see our essay Citizenship in Providence, RI: the long road to rights [link]

Colonel Olney did what he could for his men after the war. He wrote to both the national and state governments on the men’s behalf to secure their promised benefits, especially their pensions. In addition, he provided proof of citizenship certificates to protect them as sailors (the British would often “impress” American sailors to work on British naval ships if they had no papers), and he fought attempts to re-enslave them.21Crotta Brennan, p.27 In 1790, one former enslaver cited that he had not received compensation for a soldier named London Hall. In a petition addressed to the General Assembly, the enslaver insisted upon either receiving an amount of money or the right to re-enslave London. Olney was placed on a committee to investigate, and the committee recommended that London’s three-year service was enough time to exchange for his freedom, so the claim was denied.22Geake, Robert G. and Zilian, Fred, “Patriot’s Park.” Rhode Island Slave History Medallions

Very few of the men received any credit for their accomplishments while they were alive. Even in Rhode Island, public recognition was not achieved until 1976. At Portsmouth, Rhode Island, near where the men fought in 1778, a monument to the regiment was erected at Patriot’s Park.23Geake & Spears, p. 130 The site has been expanded and now contains a list of all of the soldiers who served during the war that gained not only our nation’s freedom but also, for many, their own.24“The Battle of Rhode Island”, The Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 2006

Terms:

Regiment: the basic military unit used during the war usually comprising of a few hundred soldiers. Also referred to as a “Battalion” in some records

Loyalist: person loyal to the British government

Indigenous: original people of an area, in this case a member of one of the Native American groups in Rhode Island such as the Narragansett

Race: a social construct which groups people together based on physical or other attributes. Skin color is an example

Pension: money paid to someone after retirement

Negro: a term used to describe people of African descent or with dark-colored skin. This is an old term that is now considered disrespectful. However, some people still self-identify with this term. You may also come across the terms African American, Black, person of color, colored person, or colored

Mulatto: an old term used to label a person of mixed race or multi-racial

Muster: enlisting into military service

Bounty: a reward, premium, or subsidy when offered or given by a government

Pound: primary monetary unit of the British government

Lobby: to influence politicians to act or vote a certain way on a particular issue

Hypocritical: pretending to be what one is not, a pretense of virtue

Quota: the share or proportion assigned to each member

Hessian: German troops fighting on the side of the British

Segregated: set apart from each other. In this case, it was common to separate the races into different units so that men of color and white men did not serve together

Indenture: a form of enslavement that is not inherited and ends after a set period of service. It is set apart from chattel slavery which is inherited and for life

Privateers: private individuals who were given rights by their governments to use their ships to rob and pillage enemy ships from other countries during war. These acts were sanctioned by law unlike pirating which was against the law

Warning out: the determination of residency by reviewing a person’s place of birth. This system was used by local town governments to claim that a person was actually the responsibility of another town at a time when towns used monetary funds to support a person who was unable to support themselves

Questions:

The beginning of this essay mentions embarrassment on behalf of the colonists about enslaved individuals fleeing to British lines to guarantee their freedom? Why do you think that would embarrass the colonists?

Why do you think enslavers were petitioning the decision to allow enslaved men to join the army? What about enlisted enslaved people do you think would threaten enslavers?

This essay states that public recognition for the service of the First Rhode Island Regiment was publicly achieved until 1976. If they served in RI in 1778, why do you think it took almost 200 years for public recognition? What does this tell us about how we remember history in the United States?

- 1“The Pines Bridge Monument” [link]

- 2Robert A. Geake & Loren M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution, Westholme Publishing, 2016, p. 20

- 3“Governor Cooke to George Washington, February 23, 1778” Rhode Island State Archives, Digital Collection, African-American Collection

- 4Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, New York University Press, 2016, p.70

- 5“The Battle of Rhode Island” The Rhode Island Society of the Sons of Liberty. 2006

- 6Robert A. Geake and Loren M. Spears.From Slaves To Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution. Yardley, PA, Westholme Publishing LLC. 2016.p. 21

- 7John U. Rees, “‘They Were Good Soldiers’: African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783”, Helion & Company, 2019, p. 36

- 8Rhode Island State Archives, C#0210-Acts and Resolves of the General Assembly. v. 17, no. 4

- 9“Letter regarding inadequate pay for slaves in Colonel Greene’s regiment, September 3, 1779”, Rhode Island State Archives, Digital Collection, African-American Collection

- 10Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, p. 72

- 11Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, p. 72-73

- 12John U. Rees. “They Were Good Soldiers” African Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783. Warwick, England Helion & Company. 2019. p.29

- 13“Letter from Captain Elijah Lewis to the Speaker of the General Assembly, March 13, 1778.” Rhode Island Digital Archives, African-American Collection

- 14Rees, “They Were Good Soldiers”, p. 73

- 15Geake & Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers, p. 42-45

- 16Patrick T Conley, “The Battle of Rhode Island,29 August 1778: A Victory for the Patriots,” Rhode Island History. v. 62, no. 3(Fall 2004), p. 53-58

- 17Linda Crotta Brennan, The Black Regiment of the American Revolution, Moon Mountain Publishing, North Kingstown, RI, 2004, p 25

- 18Ibid, p.26

- 19Grundset,Eric G.,ed. Forgotten Patriots: African Americans and American Indians in the Revolutionary War, Washington, D.C.; National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. 2008

- 20Geake & Spears. From Slaves to Soldiers. p. 98; For more information on Warning Out, see our essay Citizenship in Providence, RI: the long road to rights [link]

- 21Crotta Brennan, p.27

- 22Geake, Robert G. and Zilian, Fred, “Patriot’s Park.” Rhode Island Slave History Medallions

- 23Geake & Spears, p. 130

- 24“The Battle of Rhode Island”, The Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 2006