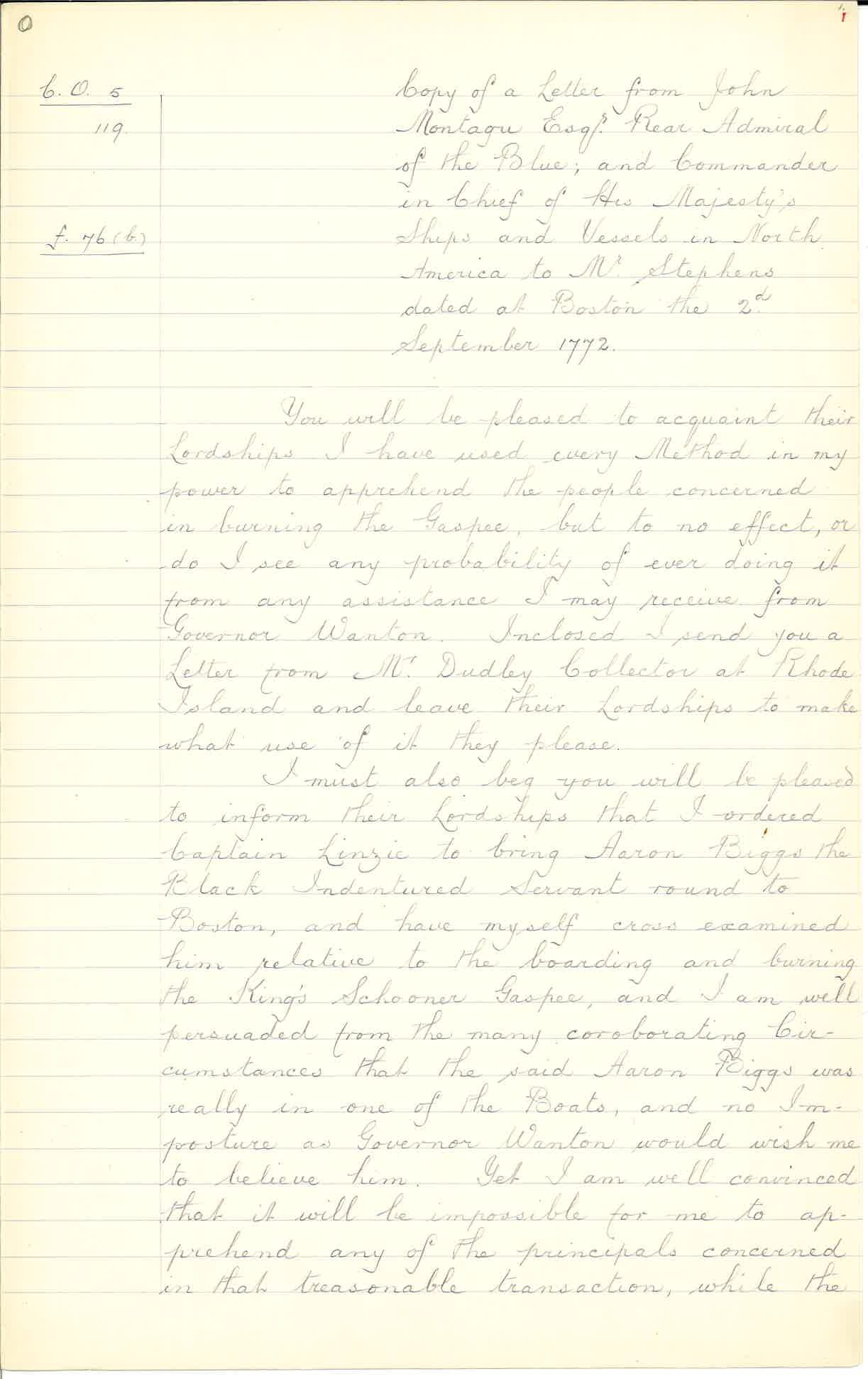

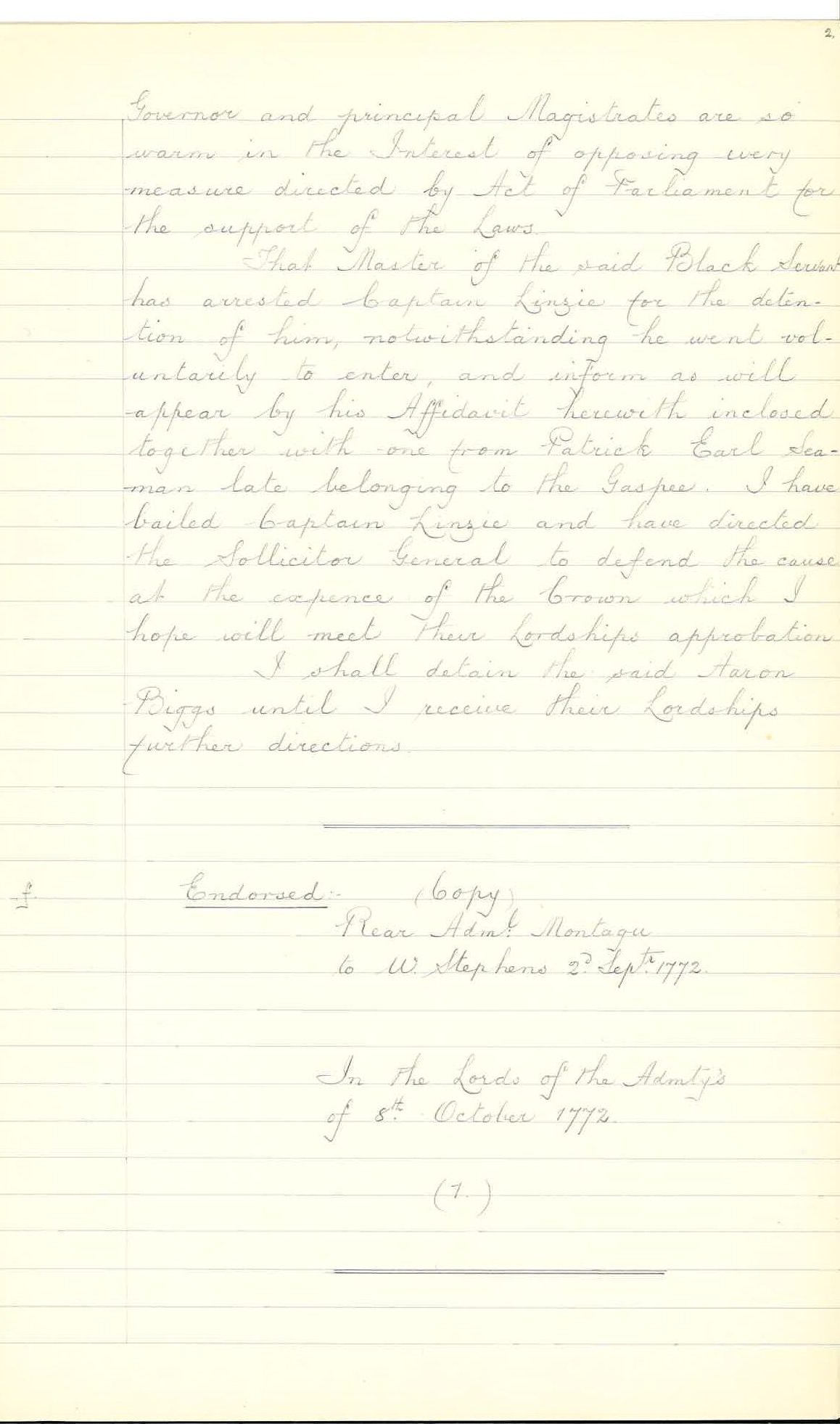

Copy of a letter from Rear Admiral Montagu to Mr. Stephens in the British Parliament

This is a copy of a letter from John Montagu Esq. Rear Admiral of the Blue, and Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Ships and Vessels in North America to a Mr. Stephens in the British Parliament. It is dated at Boston on September 2, 1772.

The Gaspee Affair and the Boston Tea Party: On the Road to Revolution

Essay by Jackson Piantedosi, Rhode Island Historical Society Education Intern, student at Providence College

On the night of December 16, 1773, Massachusetts Bay Colony pushed Great Britain’s thirteen colonies dangerously closer to open rebellion. That night in Boston, angry merchants and townsmen marched down to the docks of Boston Harbor and dumped a full shipment of the King’s tea into the sea. The participants, some dressed as Native Americans, were protesting the British Parliament’s right to impose taxes on the colonists, even though the colonists lacked representation in Parliament and, outside of extrajudicial means, were largely powerless to oppose laws they saw as unfair or unjust. This complaint was expressed with the famous cry of “no taxation without representation,” which was born during protests over the Stamp Act a decade earlier. This act of defiance enraged the government of Great Britain, who responded with the Coercive Acts, which the colonists referred to as the “Intolerable Acts.” These new laws closed Boston Harbor to trade and removed the right of Massachusetts colonists to govern themselves. Nine months after the Boston Tea Party, in September of 1774, the first Continental Congress was formed to coordinate protests against what they considered oppressive British colonial rule. Then, in the spring of 1775, the first shots of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord.1Peter C. Messer. “A Most Insulting Violation; The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” New England Quarterly. v. 88, Issue 4. December 2015. p.582-622; Benjamin Warford-Johnston. “American Colonial Committees of Correspondence: Encountering Oppression, Exploring Unity, and Exchanging Visions of the Future.” The History Teacher. v. 50, No. 1. November 2016. pp. 83-128

The Boston Tea Party represents a turning point in American colonial history. A growing number of colonists began to put aside their regional and economic differences to oppose British colonial policies. Accordingly, the event maintains a prominent place in United States history textbooks and is fundamental to any teaching of the American Revolution.

However, 50 miles south of Boston, another less familiar event occurred that also edged the colonists closer to rebellion. On a summer night in 1772 in Providence, Rhode Island, another group of angry colonists boldly defied the British Crown, and in doing so, set a precedent that paved the way and lit the fuse which culminated in acts like the Boston Tea Party. The burning of the HMS Gaspee in June of 1772 “marked the end of the period of calm which had prevailed since the repeal of the Townshend Acts and the beginning of the series of events that ultimately led to revolution.”2William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. p. 233 The act of defiance continued to prove to colonists that bold acts were effective in resisting British rule. In addition, the weak response of the British government that followed gave colonists, especially those in Boston, the mistaken idea that their acts of resistance would go relatively unpunished, further motivating them to take the dramatic measure they did on that December night in 1773.

The situation in 1772 Providence, Rhode Island, was not much different than the situation in Boston, Massachusetts. As you read in the main essay, British customs officials, who were charged with making sure that the colonists were following the laws put forth by the Navigation Acts had become stricter and more forceful in carrying out their duties. The laws that they were enforcing required that the colonists only trade for products that came from within the British Empire and that taxes were paid toward these products. These laws provided the British government with much-needed revenue following the costly victory over the French in the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in the colonies). The customs officials would board ships to ensure that the merchants had paid their fair share to the British Crown and that the cargoes they carried were legal– a practice that the colonists saw as harassment. One customs official, Lieutenant William Dudingston, had earned a reputation among the colonists of Rhode Island as particularly aggressive and rude. In one incident, Lt. Dudingston sent illegal cargo of undeclared rum he had seized in Rhode Island to Boston, Massachusetts, for trial, “contrary to an act of Parliament, that required such trials to be held in the colonies where the seizures were made.”3John Russell Bartlett, ed. Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Volume VII: 1770-1776. Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1862. p.60 [link] By doing so, Lt. Dudingston had not only ignored regulations but had also broken the chain of command by going behind the back of the Governor of the colony of Rhode Island, Governor Joseph Wanton, who was typically charged with handling these trials.

Recognizing this, Governor Wanton wrote a letter to Lt. Dudingston informing him that what he had done was illegal. The reply that Governor Wanton received was perceived as rude and arrogant, with Dudingston complaining, “I have done nothing but what was my duty, and their complaint can only be found on their ignorance of that.”4Letter from Lt. Dudingston to Governor Wanton, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p.61 Governor Wanton, offended that his authority was not recognized, wrote a letter to Lt. Dudingston’s superior, Rear Admiral Montagu stationed in Boston, and informed the Rear Admiral that he did not know “whether he [Dudingston] came hither to protect us from pirates, or was a pirate himself.”5Letter from Governor Wanton to RA Montagu, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island p.63 Rear Admiral Montagu took the side of Lt. Dudingston, creating a situation where the government of Rhode Island and Royal customs officials were at odds with one another. As the people of Rhode Island learned of this incident, they were outraged at what they saw as a double standard that British officials did not receive the same punishment that the colonists did when they broke the law.

Given this background, it becomes clear that by the night of June 9, 1772, both sides were ready for a confrontation. Lt. Dudingston, in command of the ship the HMS Gaspee, attempted to board and harass the colonial ship Hannah. The sailors on board the Hannah fled and, because of their superior knowledge of the waters of Narraganset Bay, led the Gaspee into shallow waters where she ran aground. Dudingston had to wait until high tide to try to free his ship, so until late that night, the Gaspee would be unable to move. Meanwhile, word of the Gaspee’s situation spread quickly to the residents of Rhode Island, who jumped at the opportunity to finally rid themselves of the harassment that the ship and Lt. Dudingston had caused them for so long. One well-known merchant, John Brown, known even by British officers, was particularly enthusiastic about destroying the ship. In an account given by Ephraim Bowem, a participant in the incident, he claims that, “Mr. Brown immediately resolved on her destruction.”6Testimony of Col. Ephraim Bowem, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p.69 John Brown and a group of Rhode Islanders rowed up to the HMS Gaspee and shot and wounded Lt. Dudingston, becoming, “an earlier ‘shot heard ‘round the world.’”7William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. v. 39, no. 2. September 1952. p. 233 They then proceeded to burn the ship down to the waterline in an act of defiance that would send shock waves over all thirteen colonies.

When word of the incident spread across the Atlantic Ocean, the British government was outraged. Remembering a long history of maritime protests that began with riots surrounding the impressment of American sailors and anti-Stamp Act protests in the two decades prior, they had finally had enough. The incident was seen as a criminal act. Lord Dartmouth, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, claimed it was“ considered in no other light than as an act of high treason.”8Letter from Lord Dartmouth, September 4, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society Although the British government quickly moved to prosecute those who had taken part in the burning of the Gaspee, it became apparent almost immediately that it would be impossible to bring those responsible to justice, despite the fact that the organizers of the Gaspee affair were among the most well-known citizens of the colony. Although Governor Wanton established a commission to investigate what had happened that night, the investigation would fail to collect enough evidence to indict a single person, largely due to the efforts of Governor Wanton himself. In a letter written by Rear Admiral Montagu, Lt. Dudingston’s superior, he complains that, “I have used every method in my power to apprehend the people concerned in burning the Gaspee, but to no effect.”9Letter from RA Montagu to a Mr. Stephens, September 2, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society He adds, “nor do I see any probability of ever doing it from any assistance I may receive from Governor Wanton.”10Letter from RA Montagu to a Mr. Stephens, September 2, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society This same conclusion was reached by an unknown individual in an unsigned letter written on June 16, 1772, only a week after the incident, “if it is left to this government [the Rhode Island Colonial Government] to find out the perpetrators they will I am confident remain very safe.”11Unsigned Letter, June 16, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society

The incident passed without any serious punishment for the colonists of Rhode Island, a fact that Boston noted and led the attorney general of Rhode Island, Henry Marchant, to believe that “The American Congress may be much nearer than the greatest prophet has ventured to predict.”12Peter C. Messer. “A Most Insulting Violation: The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” The New England Quarterly. p. 584

Word of the incident spread to Massachusetts in a short amount of time, where the colonists received the news with excitement. Opinion pieces written for the Providence Gazette urged readers to either “prevent the fastening of the infernal chains now forging for you… or nobly perish in the attempt.”13John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p. 113 This represented a growing anti-British sentiment that continued to spread throughout the colonies. It was on display among the citizens of Boston the following January at a town hall meeting in Dorchester, where it was claimed that “it is incumbent upon the people to be watchful; and especially at this time, when we are alarmed with a new and unheard-of grievance.”14Town Hall Meeting in Dorchester, January 4, 1773; John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island p. 114 The Gaspee affair had implications for both those loyal to the Crown and those that opposed it.

One person who immediately recognized what would happen should the British government fail to punish anyone in the Gaspee incident was Thomas Hutchinson, the Loyalist governor of Massachusetts. He knew that the feelings of those colonists in Providence were shared by the citizens of Boston and recognized that they would see the failure to punish the participants of the Gaspee affair as a weakness. In a letter addressed to John Pownall, a member of the British Parliament, Hutchinson wrote,

“If it is passed over without a full inquiry and due resentment, our liberty loving people will think they may with impunity commit any acts of violence, be they ever so atrocious, and the friends to government will despond and give up all hopes of being able to withstand the faction.”15Letter from Governor Thomas Hutchinson to Secretary Pownall, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p. 102

Hutchinson expressed his fear that colonists in Boston would see the Gaspee incident as proof that the British government was unable to control even the most extreme colonial reactions. It became clear to the colonists that they had more freedom to protest the enforcement of customs laws than they previously believed.

The British government attempted to learn from their mistake in handling the Gaspee affair yet took the wrong lesson in the wake of the Boston Tea Party. The British government now knew that far more extreme measures were required in order to control unruly colonists. This new attitude was summed up by Lord Mansfield, lamenting that “Things will never be right until some of them [protesting colonists] are brought over [to England for trial].”16William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. p.255 Therefore, in the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party, instead of relying on the colonial governments to carry out justice, they took matters into their own hands. In response to the Boston Tea Party, the culmination of violent resistance that began with the Gaspee affair, the British government closed Boston Harbor to commerce and revoked the colonists’ rights to govern themselves, a reaction that frightened all thirteen colonies. The First Continental Congress was formed to uniformly oppose the measures taken by the British government, and not long after that, the first shots of the American Revolution rang out.

Terms:

Parliament: the highest legislative body in the United Kingdom. It is similar to the United States Congress

Extrajudicial: outside of court

Stamp Act: a 1765 Act from British parliament imposing a tax on newspapers and legal and commercial documents

Precedent: an act or action that serves as an example for acts or actions that occur later

HMS: stands for “His Majesty’s Ship.” HMS is the prefix given to ships in the Royal British Navy

Customs Officials: the people in charge of making sure goods are not brought into a country without paying taxes

Undeclared: an item or items brought into a country without announcement to a customs official to avoid paying taxes

Double Standard: a rule or law applied in different ways to different people

Treason: betrayal. Betrayal against one’s country is a crime

Prosecute: bring a person to court who has been accused of a crime

Commission: a group appointed by law to work together to gather information

Indict: formally charge someone with a crime

Loyalist: a person who remains loyal to the established ruler or government even in the face of revolution. In this instance, a person who remains loyal to the British government rather than the establishment of an American government

Impunity: not be punished for actions

Questions:

Would you consider the actions taken by the colonists in the Gaspee Affair and the Boston Tea Party Extreme? Why or why not?

Can you identify any similarities between these events and actions taken by citizens today who disagree with government actions? Any differences?

- 1Peter C. Messer. “A Most Insulting Violation; The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” New England Quarterly. v. 88, Issue 4. December 2015. p.582-622; Benjamin Warford-Johnston. “American Colonial Committees of Correspondence: Encountering Oppression, Exploring Unity, and Exchanging Visions of the Future.” The History Teacher. v. 50, No. 1. November 2016. pp. 83-128

- 2William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. p. 233

- 3John Russell Bartlett, ed. Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Volume VII: 1770-1776. Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1862. p.60 [link]

- 4Letter from Lt. Dudingston to Governor Wanton, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p.61

- 5Letter from Governor Wanton to RA Montagu, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island p.63

- 6Testimony of Col. Ephraim Bowem, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p.69

- 7William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. v. 39, no. 2. September 1952. p. 233

- 8Letter from Lord Dartmouth, September 4, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 9Letter from RA Montagu to a Mr. Stephens, September 2, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 10Letter from RA Montagu to a Mr. Stephens, September 2, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 11Unsigned Letter, June 16, 1772, Gaspee papers, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 12Peter C. Messer. “A Most Insulting Violation: The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” The New England Quarterly. p. 584

- 13John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p. 113

- 14Town Hall Meeting in Dorchester, January 4, 1773; John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island p. 114

- 15Letter from Governor Thomas Hutchinson to Secretary Pownall, John Russell Bartlett, Colonial Records of Rhode Island, p. 102

- 16William R. Leslie. “The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. p.255