On the Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee in 1772

Essay by Steven Park, Ph.D., Director of Academic and Scholarly Technology at Wheaton College (IL)

The Gaspee Affair, which took place in June 1772, offers a snapshot of an event situated in a much larger picture of British colonial rule and acts of resistance by British colonists that would eventually lead to calls for independence. To understand the events that took place on the night of the Gaspee attack, we must understand the way of life of Rhode Island colonists in the 1760s and 1770s, as well as general attitudes toward the British Empire at the time.

The British Empire spanned continents in the 1700s. It expanded even further after the treaty was signed that ended the French and Indian War (known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe). The terms agreed to in the treaty stated that France would cede some of its colonies in the Caribbean as well as its land claims in North America that stretched from Canada down to what is Alabama today, to the British.1Nick Bunker. An Empire on Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2014. p. 7 This meant that the British Empire controlled land in Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and North America, including the colonies that would become the United States of America.

The far reach of the empire allowed colonists under British rule in different parts of the world to trade different kinds of goods with one another, and this increase in trade made merchants very wealthy. However, much of the capital gained through this trade came from the trans-Atlantic slave trade and depended upon the labor of enslaved people.2Joey DeFrancesco. “The Gaspee Affair was about the business of slavery.” UpriseRI. June 9, 2020 [link] ; See also our chapter Rhode Island, Slavery, and the Slave Trade [link]

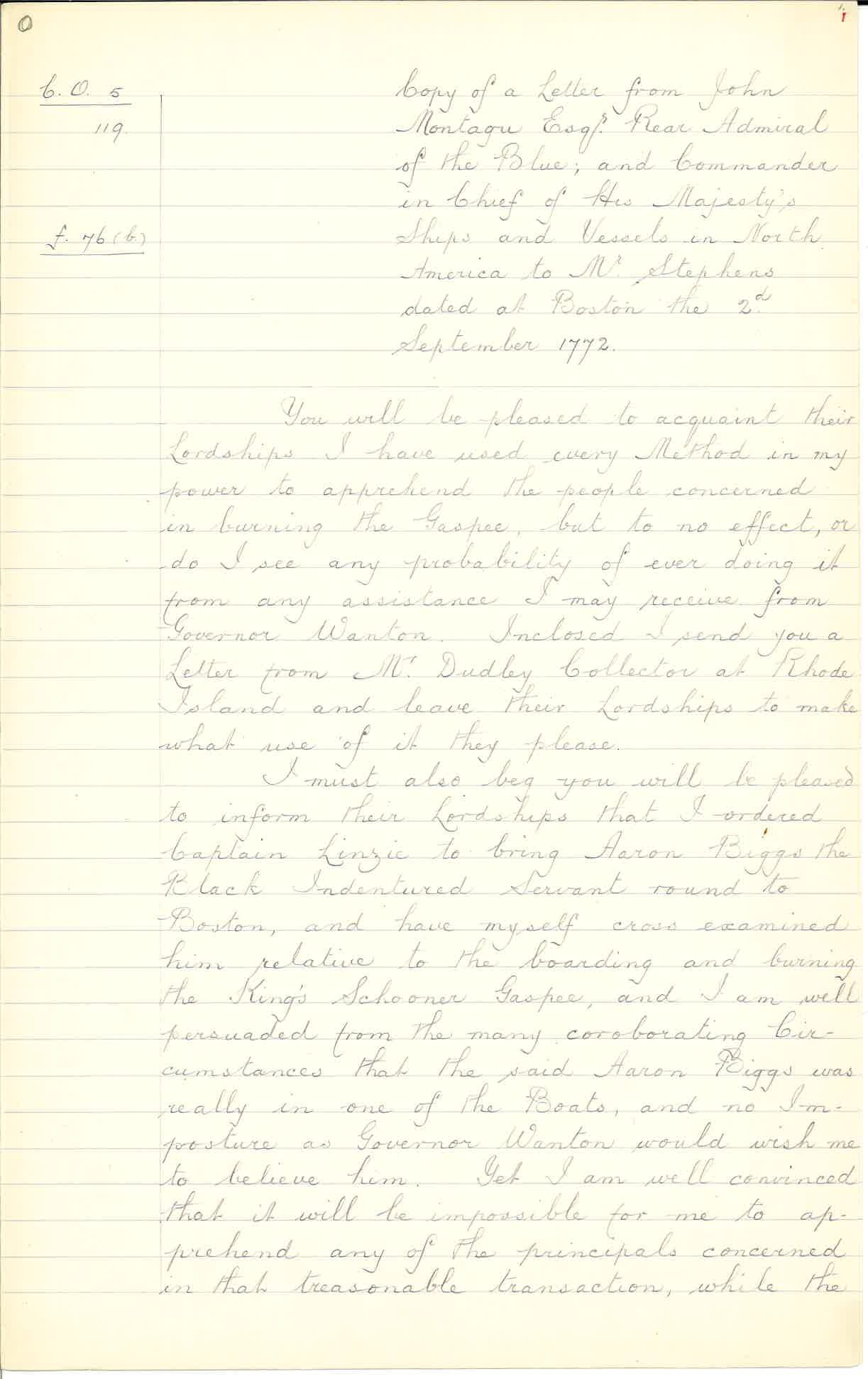

Copy of a letter from Rear Admiral Montagu to Mr. Stephens in the British Parliament

Learn how the handling of the Gaspee Affair may have influenced the Boston Tea Party here

Because of their help with the British victory in the French and Indian War in 1763, Rhode Island colonists had war receipts that they hoped to collect. In their eyes, the London government owed them gratitude and thousands of pounds (British currency). Therefore, they were shocked and angry when, rather than being thanked and reimbursed for their wartime service to the Empire, they were burdened with additional taxes to help the London government service its large war debt!3James B. Hedges. The Browns of Providence Plantations: Colonial Years. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1952 The insult of no gratitude or payment, added to the injury of heavier taxes, contributed to the colonists’ attitude of resistance to the heavy taxes imposed on them by the British government.

Because Rhode Island was a British colony, the British government legally controlled who Rhode Island could trade with and what they could trade.4Steven Park. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An Attack on Crown Rule Before the American Revolution. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. 2016. p. 3-6 Most Rhode Island merchants accumulated wealth through the legal and illegal trade in rum, sugar, molasses, and tea, among other items.5Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.48-49 These items were directly tied to the trans-Atlantic slave trade as sugar was harvested by enslaved laborers in the Caribbean and turned into molasses, which was shipped to New England, used to make rum which was then shipped to the coast of Western Africa to be traded for enslaved people.6DeFrancesco, “The Gaspee Affair was about the business of slavery”

Illegal trading and casual smuggling of goods in the North American colonies had been going on for decades due to the inefficient nature of enforcing these laws on the part of the British. It took too much time and too much money to constantly police the trade of New England merchants.7Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, p.4 But suddenly, in 1771, British naval ships started seeking out smugglers to address their serious offenses and collect taxes on the goods they were smuggling. This change occurred because the British Empire’s economy was collapsing in the early 1770s due to poor decisions being made by British colonial officials in Asia and the mishandling of the tea trade in China.8Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.41-49 The British needed money to address the failing trade economy as well as to pay off their war debts.

Throughout the 1760s, colonists up and down the Eastern Seaboard, and especially in Southern New England, participated in protests and riots to resist new and increasing taxes. By 1772, things had mostly quieted down, and all the taxes had been repealed except for the one on the importation of tea.9Professor Maier explained how rioting was used to enforce what colonists believed were just laws. Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1972

Despite the wealth and control the British Empire accumulated all over the globe, the expansiveness of the British Empire had a big downfall, too. Because the Empire was so big, their authority over the colonies was hard to enforce. They simply did not have enough resources to enforce colonial rule in all of the colonies, all over the world. The British’s inability to control its colonial subjects, in this case in Southern New England, was sometimes unknown to them “until it had become impossible to prevent.”10Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.11

Origins of the Schooner Gaspee

British naval officers had commissions, or appointed duties, that were tied to the ships they served on. If their ship was decommissioned, they would no longer be a naval officer. In an effort to keep some of its officers on the payroll, after their ships were decommissioned, the Navy gave “dual commissions.” A commander might have a commission with the customs service to enforce customs regulations while at the same time continuing to hold on to their commission in the navy on their ship. Given the crippling debt of the British Empire, the ability to aggressively collect customs duties was especially important.11Thomas C. Barrow. Trade and Empire: The British Customs Service in Colonial America, 1660-1775. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1967

One of these ships tasked with enforcing the laws of the trade was the Gaspee. Lieutenant William Dudingston served in command of the Gaspee and was not well-liked by local merchants. He was known to be an aggressive customs official, likely due to his own interest in gaining wealth. Dudingston would receive a share of the proceeds for the sale of every smuggling American vessel and its cargo he seized.12Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.53

There was a century-long tradition of resistance to customs officials in the English–speaking colonies of North America. Customs vessels had been attacked and burned, and officials had been abused, especially in Rhode Island and Southern Massachusetts. For example, the British seized a vessel called the Swanzey and its cargo in February 1772, claiming it didn’t have the necessary papers for the goods it was carrying. While the customs officials waited overnight to escort the Swanzey, via armed guard, to a British navy base to be dealt with, Americans overtook the Swanzey, seized the crew, took their weapons, and put them in small boats to row back to shore in the freezing cold. In the morning, Dudingston appeared with the Gaspee to pick up the naval officers attacked by the Americans. They set off looking for the Swanzey but couldn’t find it. Then, shots were fired at the Gaspee by Americans onshore and in boats. The British officials fired back, but eventually, both sides backed down. Even still, word of this incident spread, and Dudingston became one of the most hated men among New England colonists.13Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.54-55

What happened on that June night in 1772

The Gaspee had already been in Rhode Island for five months by June 1772. Its commanding officer, Lieutenant Dudingston, had a reputation for being a hard-driving, violent man, as described above. He had created such a negative reputation for himself that Nathanael Greene, a local merchant and later general in Washington’s Army in the American Revolution, would write that Dudingston created a “Spirit of Resentment that I have devoted almost the whole of my time in devising measures for punishing the offender,” the offender in this case, being Dudingston.14“Greene to Samuel Ward, April? 1772,” in Showman, Papers of General Nathanael Greene, p. 26; quoted in Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p. 56

On the afternoon of June 9th, the Beaver, the other British vessel stationed in Narragansett Bay, left the Gaspee alone. What happened next is in dispute and depends on which witnesses you consult. We have one side of the story told by two colonists who wrote down their recollections of that night decades later. Lieutenant Dudingston got to tell his side of the story at his court martial later that year. The Rhode Islanders claimed they lured the Gaspee into a sandbar with a small, light vessel called the Hannah, owned by prominent merchant John Brown. Dudingston claimed that he ran aground at Namquid Point because he did not have his local pilot with him and lacked knowledge of the Bay.15Namquid Point was renamed Gaspee Point immediately following this incident Dudingston used the opportunity of being run aground and waiting on the tide to set his vessel free to have his men do some routine maintenance on the vessel. The crew spent the hot afternoon waist-deep in the water, scraping barnacles off the hull.16Ephraim Bowen [link] and Dr. John Mawney [link] recorded their accounts of that night decades later. While some historians may be skeptical of human memory after such a long period of time, their stories are very similar. But that could also be because they spoke with each other about that night over the intervening years, reinforcing each other’s memory.

Inspired by their hatred for Dudingston, their resentment of British taxes, and their desire to continue illegal trading to amass as much wealth as possible, local colonists decided this would be their best opportunity to neutralize the Gaspee. At about 10 o’clock that evening, a local boy was heard beating a drum around the streets of Providence, and the local Sons of Liberty gathered at Sabin’s Tavern to discuss what they might do about the Gaspee’s vulnerable position. The beating of a drum was the traditional call for local militia to muster. They melted down some lead into bullets and departed in longboats to confront the stranded Gaspee sailors.

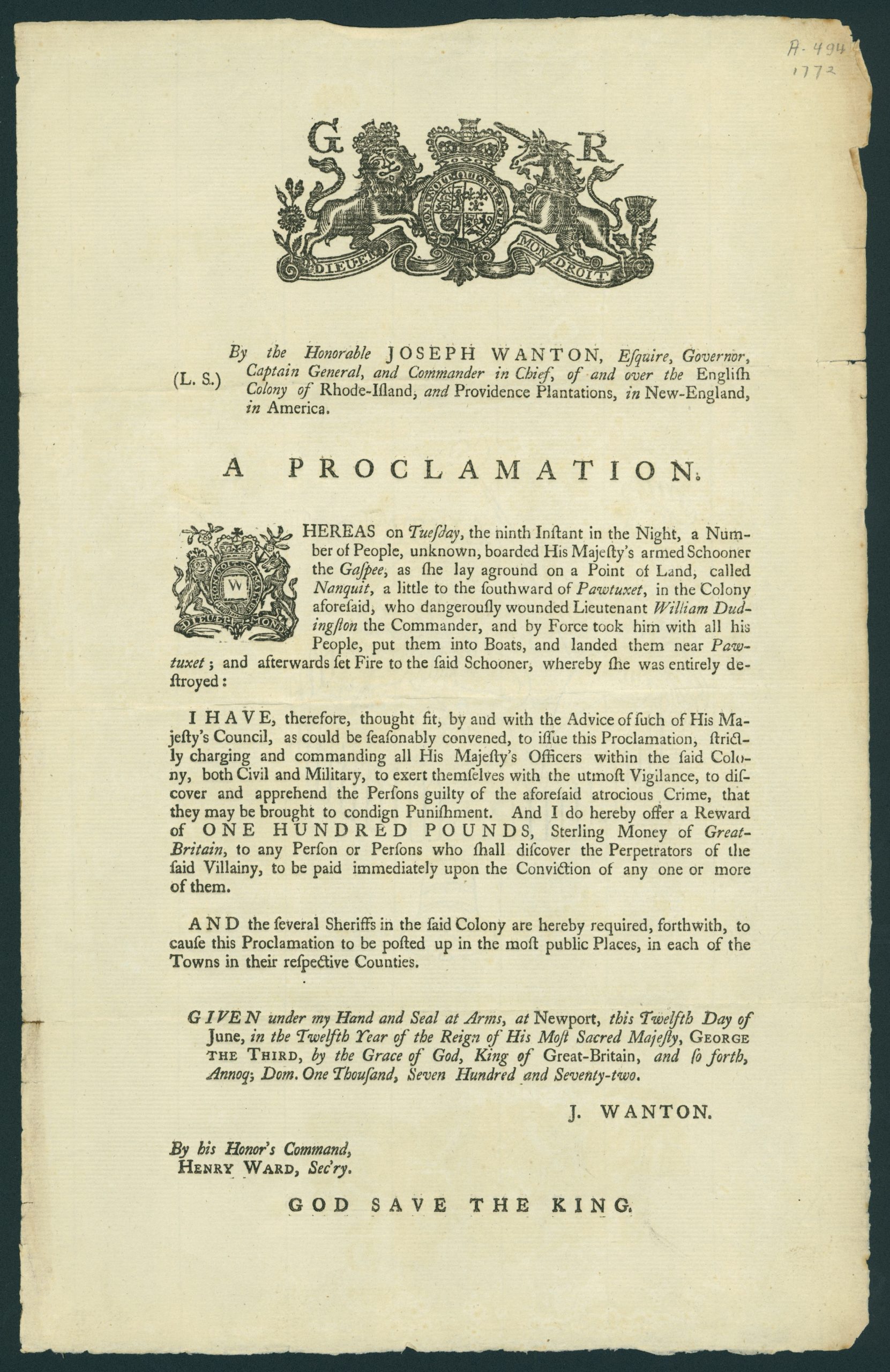

A Proclamation by Governor Wanton

Learn about the commission formed to investigate the burning of the Gaspee here

As best we can tell, by the phases of the moon and the time of day, it would have been extremely dark at 2:00 in the morning of June 10th. Colonists claim there were approximately eight longboats with about 64 men. Dudingston claimed there were dozens of vessels comprised of about 250 men. The Gaspee was understaffed with 19 sailors, all of whom were down below deck and asleep except for one lone lookout. Their small arms were locked up in a chest, and thus, the crew of the Gaspee were unprepared to defend their ship. Three components of the story told by the colonists make this look like a well-planned and intentional attack. First, the Gaspee was lured aground by following the ship, Hannah. Second, it was an exceptionally dark night. And thirdly, another longboat joined the colonists from Bristol across the bay.17Please see Dr. Concannon’s piece in the Journal of the American Revolution online [link]

When they approached the grounded vessel in the dark, someone claiming to be a sheriff (probably John Brown) stated that he had a warrant for Dudingston’s arrest (Scholars have never found this document).18In most counties, a prominent man would have the title of Sheriff, and he could call upon other upstanding men in his community to help with a crisis. Additionally, a local sheriff could write up a warrant for the arrest of a British official if they believed he was exceeding his orders or otherwise behaving in an unworthy manner But, before Dudingston could be arrested, someone got an itchy trigger finger and shot him and nearly killed him. The colonists bound and rowed the other sailors ashore unharmed. While searching the Gaspee for the orders from the Admiralty and other documents, whether on purpose or by accident, the colonists set the vessel on fire and it burned to the waterline. Everyone scattered, and by the next day, it seemed no one knew anything about what had happened the night before.19A Rhode Island Judge compiled all of the important documents surrounding the Gaspee Affair in the middle of the nineteenth century. Staples, William R. The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee. Providence: Knowles, Vose, and Anthony. 1845, 1990

The Fallout

Prior to the Gaspee, there had been little administrative follow-up on the abuse of customs officials and even vandalism against customs property. This was a different situation because the Gaspee was a commissioned naval vessel on station, and Dudingston was a commissioned officer. The Admiralty and the Privy Council could not ignore this action. However, Rhode Island already had a system of courts in place and held that London’s government could not merely step in and set up its own court.

Rhode Island’s Governor Wanton immediately offered 100 pounds for any information about the perpetrators. The British Crown subsequently offered a 500-pound reward. Ultimately, the Crown’s best legal advisors stated that they could set up a “Royal Commission of Inquiry,” a type of research group, to gather information. Additionally, these advisors noted that the only way the perpetrators could be charged with a capital crime was if they were tried for treason.

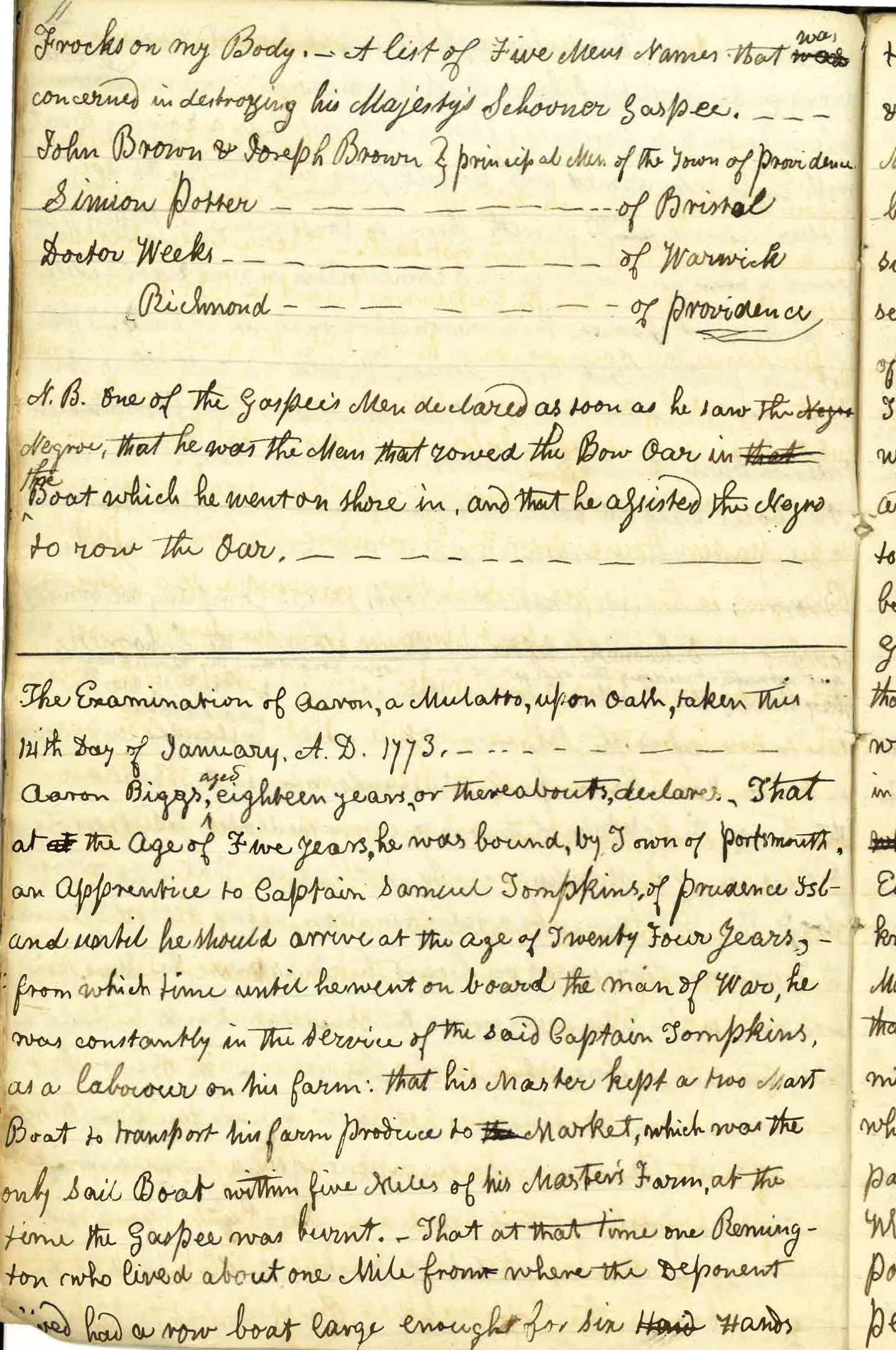

Copy of the testimony of Aaron Briggs

Learn more about Aaron Briggs here

Governor Wanton was placed at the head of this panel of interrogators. He made certain that none of the Gaspee crew were ever in the colonial house for questioning at the same time as any of the Gaspee raiders in order to prevent crew members from identifying the raiders. After months of interviews and questions, the commissioners had only one sound eyewitness, an enslaved man of African and Native American descent named Aaron Biggs (American documents show his name as Aaron Briggs) Rhode Island’s merchants and colonial officials worked to discredit his testimony to ensure he didn’t solve the mystery of the raiders’ identities, and Briggs then disappeared into the British Navy under a new identity for his own protection. It was not safe for him to return to Rhode Island after implicating powerful Rhode Island merchants. No one was ever charged with the crimes of shooting the commander or burning the vessel.20I made a chart on page 70 of my book where I showed how Governor Wanton cleverly staggered the dates and times and kept his witnesses from seeing each other. Park, Steven. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An attack on crown rule before the American Revolution. Westholme Publishing: Yardley, PA. 2016

The sailors on the Gaspee did not do a very good job protecting themselves from a group of civilians. The loss of his vessel did not hurt Dudingston’s career too much. He returned to service and retired decades later. He even returned to the colonies for a short time but served off the coast of Virginia and stayed away from Southern New England.

The Gaspee’s Legacy

So, why do we know so much about this “Gaspee Affair” and still talk about it almost 250 years later? An event that added to its legacy was a Thanksgiving Day sermon preached by a radical immigrant Baptist minister in Boston named John Allen in 1772. Ha gave his sermon at the request of Boston’s Sons of Liberty and mentioned the injustice of the Gaspee investigation seven times. Oration on the Beauties of Liberty, Or the Essential Rights of Americans, became one of the most popular pamphlets of the pre-revolutionary period. Boston patriot leader Samuel Adams helped rekindle suspicion of the motives of British officials using the Gaspee Affair and John Allen’s famous sermon. While historians can rarely draw a straight line of cause and effect, it is notable how Boston’s residents seemed empowered to throw tea into the harbor 18 months after the Gaspee Affair with little thought to the dire implications. London’s most recent response to colonial resistance seemed toothless.21John M. Bumsted and Charles E. Clark, “New England’s Tom Paine: John Allen and the Spirit of Liberty.” William and Mary Quarterly. v.21 no.4. October 1964

Terms:

Treaty: a binding formal agreement, contract, or other written instrument that establishes obligations between two or more subjects of international law

Cede: to give up power or territory

Merchant: a person involved in trade, especially one dealing with foreign countries or supply merchandise to a particular trade

War Receipts: papers that certify a person served during the war and is due payment

Triangle Trade: this term is used to describe the trans-Atlantic slave trade and comes from the triangle shape of the route many ships took. Ships would leave New England with rum, trade it on the coast of Africa for enslaved people, go to the Caribbean to trade enslaved people to work on the sugar plantations and get more sugar, then come back to New England where they’d use the sugar to make more rum

Smuggling: the illegal movement of goods into or out of a country. It is worth noting that smuggling taking place in the colonies at this time was either small scale or a “customary” ignoring of certain rules set forth in the Navigation Acts

Repealed: laws and taxes can be reversed or “repealed” by a legislature, assembly, or parliament

Decommissioned: a military term for withdrawing or retiring people and equipment

Customs: an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting duties, or taxes, and controlling what goods can come into or leave that country

Seize: to take suddenly and forcibly

Court martial: a military trial

Sons of Liberty: were a group of local patriots who used legal and sometimes extra-legal means to resist what they believed was Imperial abuse of power

Muster: to enlist into service of the armed forces

Admiralty: in the context of the Gaspee, the Admiralty is the jurisdiction of British courts of law concerning ships and the sea; those concerned with maritime law

Privy Council: a board of advisors to the British Crown

Treason: the crime of betraying one’s country

Implicate: show (someone) to be involved in a crime

- 1Nick Bunker. An Empire on Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2014. p. 7

- 2

- 3James B. Hedges. The Browns of Providence Plantations: Colonial Years. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1952

- 4Steven Park. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An Attack on Crown Rule Before the American Revolution. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. 2016. p. 3-6

- 5Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.48-49

- 6DeFrancesco, “The Gaspee Affair was about the business of slavery”

- 7Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, p.4

- 8Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.41-49

- 9Professor Maier explained how rioting was used to enforce what colonists believed were just laws. Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1972

- 10Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.11

- 11Thomas C. Barrow. Trade and Empire: The British Customs Service in Colonial America, 1660-1775. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1967

- 12Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.53

- 13Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p.54-55

- 14“Greene to Samuel Ward, April? 1772,” in Showman, Papers of General Nathanael Greene, p. 26; quoted in Bunker, An Empire on the Edge, p. 56

- 15Namquid Point was renamed Gaspee Point immediately following this incident

- 16Ephraim Bowen [link] and Dr. John Mawney [link] recorded their accounts of that night decades later. While some historians may be skeptical of human memory after such a long period of time, their stories are very similar. But that could also be because they spoke with each other about that night over the intervening years, reinforcing each other’s memory.

- 17Please see Dr. Concannon’s piece in the Journal of the American Revolution online [link]

- 18In most counties, a prominent man would have the title of Sheriff, and he could call upon other upstanding men in his community to help with a crisis. Additionally, a local sheriff could write up a warrant for the arrest of a British official if they believed he was exceeding his orders or otherwise behaving in an unworthy manner

- 19A Rhode Island Judge compiled all of the important documents surrounding the Gaspee Affair in the middle of the nineteenth century. Staples, William R. The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee. Providence: Knowles, Vose, and Anthony. 1845, 1990

- 20I made a chart on page 70 of my book where I showed how Governor Wanton cleverly staggered the dates and times and kept his witnesses from seeing each other. Park, Steven. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An attack on crown rule before the American Revolution. Westholme Publishing: Yardley, PA. 2016

- 21John M. Bumsted and Charles E. Clark, “New England’s Tom Paine: John Allen and the Spirit of Liberty.” William and Mary Quarterly. v.21 no.4. October 1964