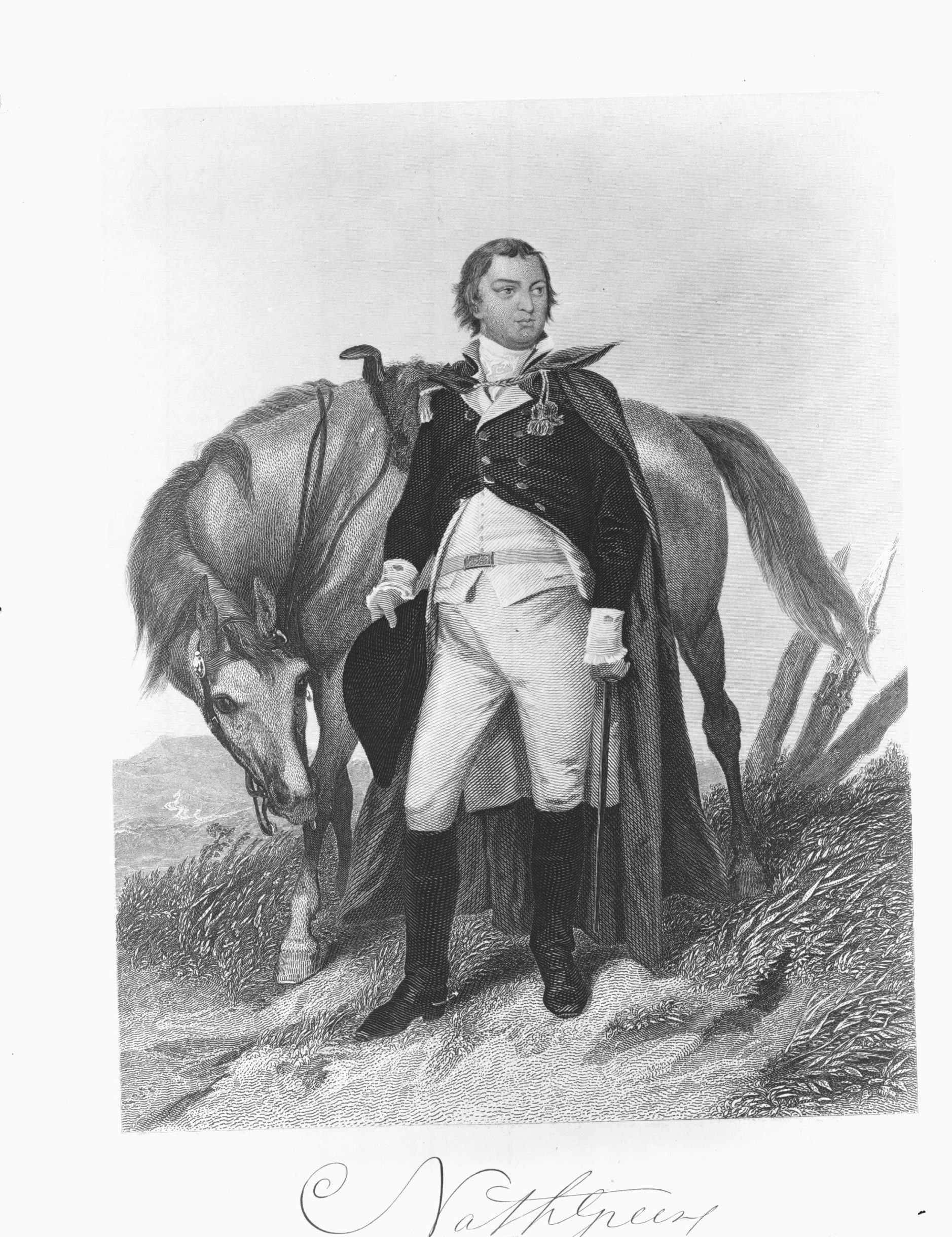

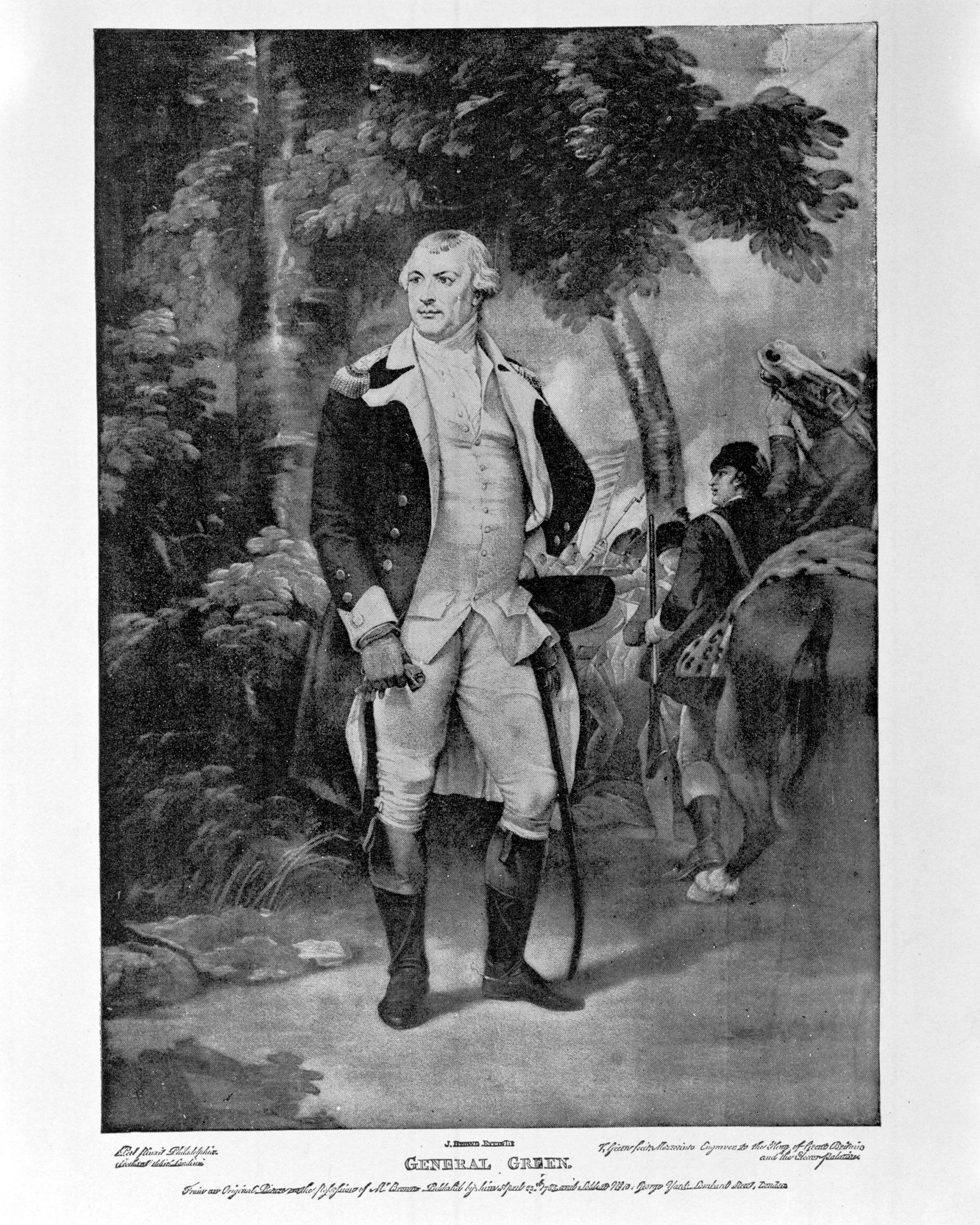

Engraving of Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene, a native of Rhode Island, was one of the generals of the Continental Army in the South during the American Revolution. Greene worked his way up from being a military novice to a respected general. He had a mind for strategy, which proved beneficial to General George Washington, and he found unique ways to play to his strengths. Nathanael Greene’s relationship with Washington, his investment in public support, and his emphasis on military intelligence made him an effective leader in the southern campaign of the Revolutionary War.

Nathanael Greene: Revolutionary Strategist

Essay by Sarah Heavren, Education Intern, Providence College

Nathanael Greene grew up in a Quaker family in Potowomut, Rhode Island. His mother died when he was eleven years old, leaving him in his father’s care. His father was a devout Quaker who promoted “pacifism, hard work, and adherence to Scripture.”1John W. Hall, “‘My Favorite Officer’: George Washington’s Apprentice, Nathanael Greene,” in Sons of the Father: George Washington and His Protégés, ed. Robert M.S. McDonald (University of Virginia Press, 2013), 152 [link] As a consequence of his father’s strict religious views, Greene did not receive much education. Additionally, the Quaker principle of anti-violence barred Greene from involving himself in military affairs. After his father died in 1770, Greene separated himself from Quaker practices to such an extent that he was suspended from the Quaker community in 1773. However, he took advantage of his freedom to educate himself on various subjects, including military practices.2Hall, 152

The outbreak of the Revolutionary War created the perfect opportunity for Greene. He served as a militia private before he became commander of the Rhode Island militia and junior brigadier in the Continental Army. Greene’s positions of authority had changed so quickly that he had little time to gain significant military experience, let alone leadership experience. However, his reputation caught the attention of General George Washington, who was willing to mentor Greene in return for advice on military strategies.3Hall, 151

Throughout the Revolution, Greene and Washington developed such a special relationship that Greene named his first two children George Washington and Martha Washington Greene. Greene “was competent, loyal, and—critically—less experienced than the commander in chief.”4Hall, 150 Washington was grateful that Greene respected him and was eager to learn. Although Greene did not have much of a military background, he had other strengths that made him an asset to Washington. As Hall writes, “Despite his lack of combat experience, Greene’s shrewd judgment and organizational abilities earned Washington’s trust.” 5Hall, 153 Greene started to build up a reputation because of his military cunning and his advising skills. He became the commander of the New Jersey militia and advised Washington’s various councils. On multiple occasions, Greene’s advice proved to be the best approach, which bolstered the reliability of his judgment.6Hall, 154

Washington was not a strategic expert when it came to military matters. While he was rooted in European traditions characteristic of the British army, Greene had a unique mind for strategy. After studying military theory and experimenting with executing various strategies, Greene proved he had developed a strong military intuition.7Hall, 156 Greene was more open to a less structured form of warfare than the formal style that Washington had been using. Confident in his mentee’s strategic abilities, Washington appointed Greene to lead the southern division of the Continental Army in October of 1780. The army that Greene inherited from General Horatio Gates was not in good condition. Gates and the southern army had suffered a serious defeat in Camden, South Carolina, just two months prior to Greene’s appointment, leaving supplies and morale low.8James Haw. “‘Everything Here Depends Upon Opinion’: Nathanael Greene and Public Support in the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine. v. 109, no. 3 (July 2008): 212 Greene’s leadership and cleverness lent a new approach to the war efforts in the South.

One of the creative strategies that Greene used was to increase public confidence. Because of the state of the army, Greene recognized that “keeping the support of the people was crucial to victory.”9Haw, 212 When the British began targeting the South in 1778 under the command of General Charles Cornwallis, they planned to occupy nearby towns and then train the loyalists there to maintain British dominance after the British had left. Greene knew facing the British would be an even greater challenge in the South than in the North, especially because southern states did not have a system in place to raise local militia. In Charlotte, North Carolina not only was Greene’s army small, but it had little military training or equipment. Greene, therefore, proposed taking a defensive stance against the British as opposed to being on the offensive. Aware that the public’s morale was already sinking, Greene did not want to risk another defeat. Greene’s decision to remain defensive is an example of his careful consideration of the capabilities of his troops.10Haw, 218-221 His strategic leadership over the following months resulted in the British abandoning South Carolina and parts of Georgia, which boosted the public’s confidence in the Continental Army and the patriot cause.11Haw, 226

As the war raged on and as supplies became scarce in the South, Greene found himself faced with the need for more men and material. However, having sympathy for the people and their struggles, he tried to compromise as much as possible. For example, although his army desperately needed horses to transport supplies, Greene declared that the soldiers should not commandeer the more valuable breeding horses and instead should leave them for the people to use. Although taking supplies from civilians as a way of supporting the army was a common military practice, he recognized that the war was economically challenging enough for people and that the army did not have the right to strip civilians of their means of support.12Haw, 227 Greene valued the public, and “from 1775 on, he ordered that care be taken to prevent plundering, destruction of property, or even insults to civilians.”13Haw, 215 Going even further, Greene made sure that those who made contributions to the army would be reimbursed unless their property was damaged as an unavoidable consequence of war.14Haw, 216

Greene also highly valued the importance of military intelligence. As Daigler states, “During the southern campaign, a war of mobility where Greene’s Continentals were numerically weaker than his enemy, timely and accurate intelligence was the key to his army’s survival.”15Kenneth A. Daigler, “Nathanael Green and the Southern Campaign,” in Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Georgetown University Press, 2014), 198 [link] Greene sought for the “identification of British and Tory units, their strength, and the details of the fortifications they defended.” Additionally, he prized information regarding British travel plans. Although incredibly useful, information regarding British tactics was especially difficult to obtain and frequently required a source from the inside – a spy.16Haw, 198 Greene knew that having military intelligence could give him an advantage against the British, despite his meager supplies and untrained soldiers.

Greene was a valuable source of military intelligence for Washington. Prior to commanding the southern forces, Greene deployed his own spies to gather information on British movements as he moved his army across the northeast, and he frequently passed along valuable information to Washington. In his personal papers, Greene documents methods for collecting intelligence, including ways of protecting both his informants and their findings.17The Rhode Island Historical Society has a nine-volume set of his transcribed papers, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, available for view at the Robinson Research Center Greene used codenames and had men who were able to decipher British codes. Other methods included sending field agents to gather information from loyal locals, interrogating prisoners of war, questioning civilians who formerly supported the British, intercepting British reports, and setting standards for spies venturing into British territory. According to Greene’s personal writings, more than twenty-five officers from the Continental Army and local militias under his command were focused on gathering military intelligence.18Haw, 199-202

During Greene’s service during the Revolution, he became a valuable asset for Washington. He was able to use his strategic mind to lead the Patriots to success. He utilized public support and military intelligence to confront the British, choosing strategy over force on the battlefield. He also brought success to the Continental Army in the South.

Terms:

Novice: a person who is new to an activity or organization and lacks experience

Quaker: a person who follows the set of religious beliefs established by the Society of Friends. One of the characteristics of Quakerism is pacifism, or avoiding violence

Militia: local military forces composed of civilians

Brigadier: the military rank that is above colonel but below major general

Commandeer: the act of taking possession of supplies or property from civilians to support the military

Tory: an American colonist who remained loyal to England during the Revolutionary War

Questions:

In what ways were Nathanael Greene’s strategies unusual?

Do you think Nathanael Greene’s strategies were successful despite being unusual? Why or why not?

Why was it important that Nathanael Greene consider the ways in which the war affected civilians despite being in dire need of supplies?

Is having a mind for strategy an essential quality in a good general? Why do you think that?

- 1John W. Hall, “‘My Favorite Officer’: George Washington’s Apprentice, Nathanael Greene,” in Sons of the Father: George Washington and His Protégés, ed. Robert M.S. McDonald (University of Virginia Press, 2013), 152 [link]

- 2Hall, 152

- 3Hall, 151

- 4Hall, 150

- 5Hall, 153

- 6Hall, 154

- 7Hall, 156

- 8James Haw. “‘Everything Here Depends Upon Opinion’: Nathanael Greene and Public Support in the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine. v. 109, no. 3 (July 2008): 212

- 9Haw, 212

- 10Haw, 218-221

- 11Haw, 226

- 12Haw, 227

- 13Haw, 215

- 14Haw, 216

- 15Kenneth A. Daigler, “Nathanael Green and the Southern Campaign,” in Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Georgetown University Press, 2014), 198 [link]

- 16Haw, 198

- 17The Rhode Island Historical Society has a nine-volume set of his transcribed papers, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, available for view at the Robinson Research Center

- 18Haw, 199-202