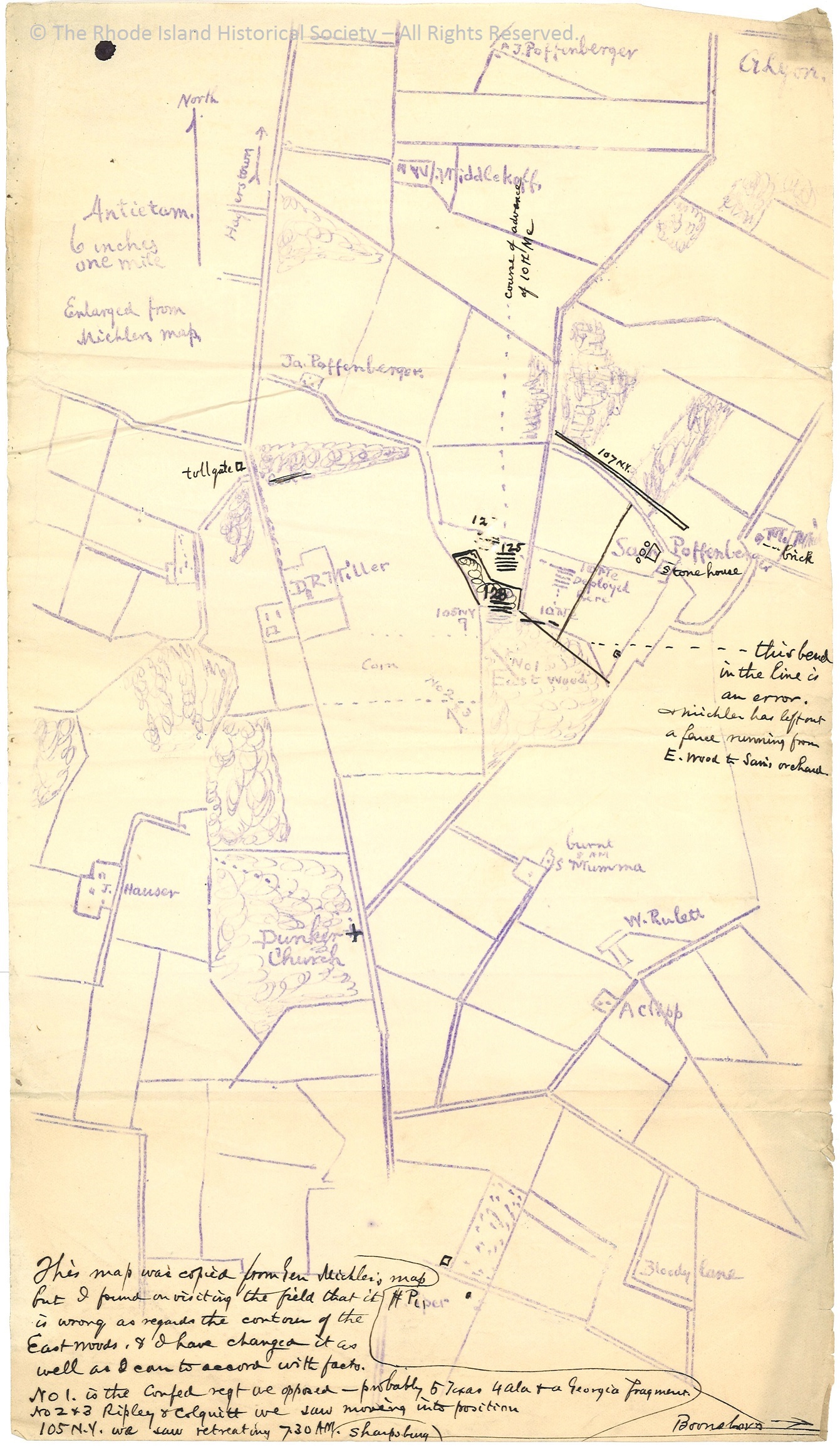

Annotated Map of Gettysburg

This hand-drawn map of the battlefield at Gettysburg in 1863 contains annotations by Brigadier General George Sears Greene after the battle.

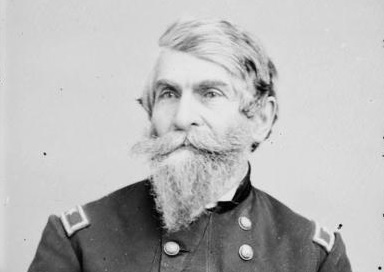

General George Sears Greene

Essay by Jennifer Galpern, Research Services Manager, Rhode Island Historical Society

General George Sears Greene, Major General by brevet, and Brigadier General of Volunteers in the service of the United States, son of Caleb Greene and Sarah Robinson Greene, of Warwick, Rhode Island was born May 6, 1801. Members of his family served in the American Revolution, and he followed in their military footsteps. He was appointed a cadet at the Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated second in the class of 1823, and was commissioned 2d Lieutenant in the 3d Regiment of Artillery. Greene was incredibly smart and was appointed as Acting Assistant Professor of Mathematics in the last year of his studies at West Point. After he was commissioned, he remained for three years at the Academy as a professor of Mathematics and one year as an Assistant Professor of Engineering. He was on duty with his regiment for several years, resigning in 1836 to devote himself to civil engineering. In this part of his professional duties, he was occupied in mining and in the laying out of railroads. He was also engaged on the Croton aqueduct in New York City, and had charge of the enlargement of the works. While he was working on these civilian, rather than military, aspects of civil engineering, the Civil War broke out.

As soon as Greene heard about the attack on Fort Sumter, which is considered the start of the American Civil War, he offered his military services to the Governor of New York, Edwin D. Morgan, where he was living at the time. In January 1862, he was commissioned by Governor Morgan to serve as the Colonel of the 60th New York Regiment. He was promoted to Brigadier General later that year and took his military services to Virginia, where he would command the Army of the Shenandoah. His bravery and military skill, shown by his many promotions, gained him the respect and admiration of his superior officers.

General Greene fought in some of the most well-known battles of the Civil War, including Antietam, Chancellorsville, VA, and Gettysburg. Greene was especially noted for his skillful strategy and heroic defense at Gettysburg. His 25 years as an engineer, designing and building railroads and waterworks, and his aggressive leadership style made him the ideal man to lead the defense of Culp’s Hill, where he made an early morning decision to construct breastworks. At that point in the war, many officers on both sides still opposed their use. Confederate General John Bell Hood, for example, felt they “would imperil that spirit of devil-me-care independence and self-reliance” that supposedly helped make Confederate troops effective. Some thought breastworks diminished soldiers’ courage. Not Greene. He believed human lives were too important to be sacrificed to bravado and unproven theories. Without the protection of breastworks, Greene’s heavily outnumbered brigade probably would have been swept from the hill to the great peril of the Union army. Under Greene’s direction, the works were perfectly located and constructed not only to protect the defenders but also to conceal them. Thus, the 4,000 to 5,000 attackers did not know their enemy was a mere 1,350 men.

In September 1863, he was transferred again and engaged in battle at the Battle of Wauhatchie on the border of Tennessee and Georgia. Greene rode his horse along the front line to lead and instill confidence in the men he commanded. He was in front of the section of artillery when it started firing, making his horse jump and breaking the saddle girth, the strap holding the saddle on the horse. He rode his horse to the rear of the line to fix it, but while he was preoccupied with his horse, he was shot through the upper jaw. The shot took out all of his upper teeth and disabled his voice so he could not command. He turned over command to his senior colonel. His face wound affected the salivary organs in his mouth, and he had the wound operated on in May of 1864. He took time away from the war during the period in which he had his injury cared for.

As soon as he was ready to return to the battlefield again, he went to Newbern, North Carolina, and joined General Schofield’s column. He then went on the advance to open communication between the cities of Beaufort and Goldsborough. Soon after, he was again wounded, but he was able to march with Sherman’s army to Washington. In Washington, he was granted the post of President of the general court-martial and presided over cases until the close of the war. Also on his arrival in Washington, he received the appointment of Major General of Volunteers by brevet in the service of the United States, to date from March 13, 1865.

After the war, Greene resumed his civil engineering career in New York and Washington, D.C. From 1867 to 1871, he was the chief engineer commissioner of the Croton Aqueduct Department in New York. At the age of 86, he inspected the entire 30-mile Croton Aqueduct structure on foot. He also became an active genealogist, and his notes were used to publish an authoritative genealogy of the Greene Family of Rhode Island.

George Sears Greene died just shy of his 98th birthday on January 28, 1899, in Morristown, N.J. His body was returned to the family plot in Apponaug, Warwick, Rhode Island. A large boulder from Culp’s Hill, Pennsylvania was placed over his grave, along with a replica of his sword and a plague commemorating his military achievements. The State of New York honored him with a bronze statue atop Culp’s Hill in the Gettysburg National Military Park in 1906.1Eric Ethier. “George Sears Greene: Gettysburg’s Other Second-Day Hero.” Rhode Island History, Vol. 53, May 1995; Eric Ethier. “King of the Hill: Grandfatherly General George Sears Greene Saves the Day at Gettysburg.” Civil War Times, Dec. 1997; George Sears Greene Collection. Rhode Island Historical Society, MSS 460

Terms:

Brevet: the promotion of a military officer to a higher rank without increase of pay. It is often granted as an honor before retirement

Commissioned: given a rank in the military upon graduation

Civil engineer: a person who designs public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, and harbors, or supervises their construction or maintenance

Croton Aqueduct: this carried water by gravity 41 miles from the Croton River in Westchester County to reservoirs in Manhattan, New York. It was built because local water resources had become polluted and inadequate for the growing population of the city

Breastworks: a low barrier, usually breast high, that is temporary and used in military defense

Saddle girth: the strap of the saddle that wraps around the horse’s underside

Salivary organs: glands in the mouth that secrete saliva

Questions:

Why is George Sears Greene an important figure in Rhode Island history? What did he accomplish during his military career?

Why were many officers opposed to constructing breastworks?

- 1Eric Ethier. “George Sears Greene: Gettysburg’s Other Second-Day Hero.” Rhode Island History, Vol. 53, May 1995; Eric Ethier. “King of the Hill: Grandfatherly General George Sears Greene Saves the Day at Gettysburg.” Civil War Times, Dec. 1997; George Sears Greene Collection. Rhode Island Historical Society, MSS 460