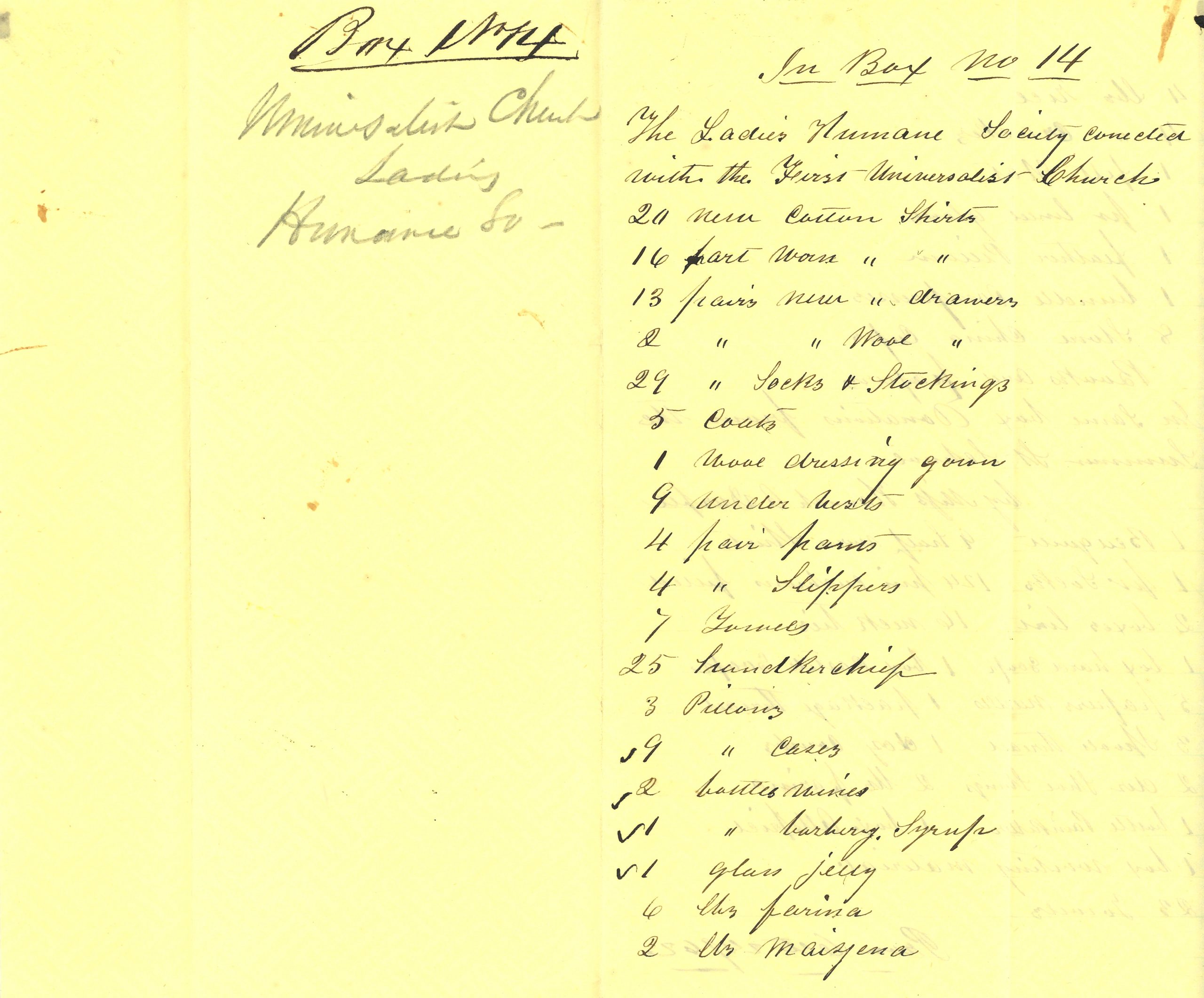

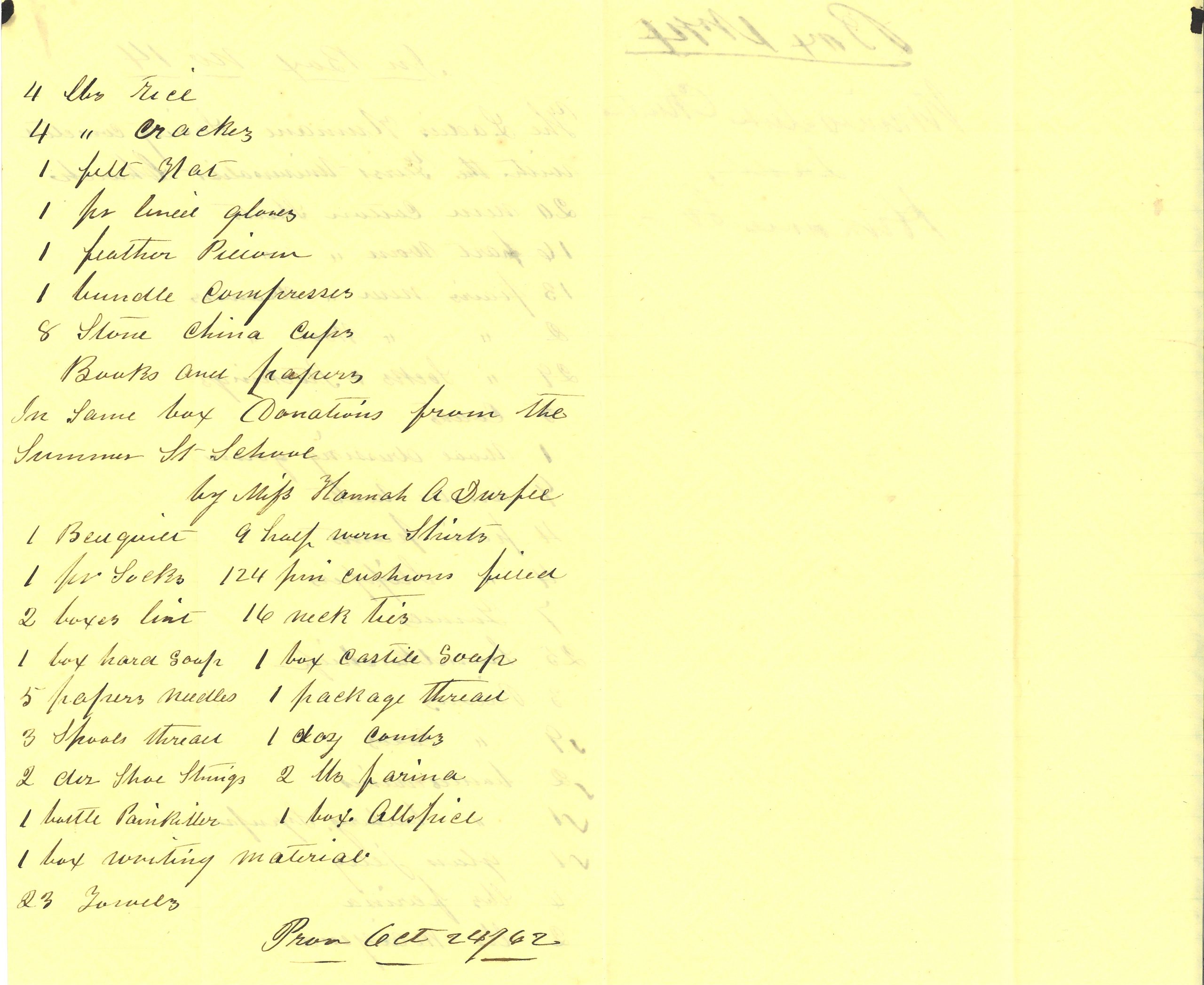

An Account of Women’s Donations to the War

This is an account showing women’s donations from the “Ladies Humane Society” and the “First Universalist Church” to the war cause. Examples of donated goods included large volumes of cotton shirts, handkerchiefs, stockings, coats, and other comfort items like homemade soap and candles.

Rhode Island’s Women on the Homefront during the Civil War

Isaac Eng, History B.A. Candidate, Brown University

Most Civil War records that we have today are the letters, business documents, and military paper trails of men. But some documents shed light on women’s wartime roles. Through the stories of a number of important Rhode Island women, we can see how working to win the Civil War did not depend only on the battlefield but also on the homefront, where women frequently predominated as politically active, hard-working, and conscientious supporters of the Union cause. From volunteer hospital work to songwriting, from housekeeping to supporting the economy in the absence of men who were the traditional breadwinners in the home, Rhode Island women were unsung but significant figures in the American Civil War.

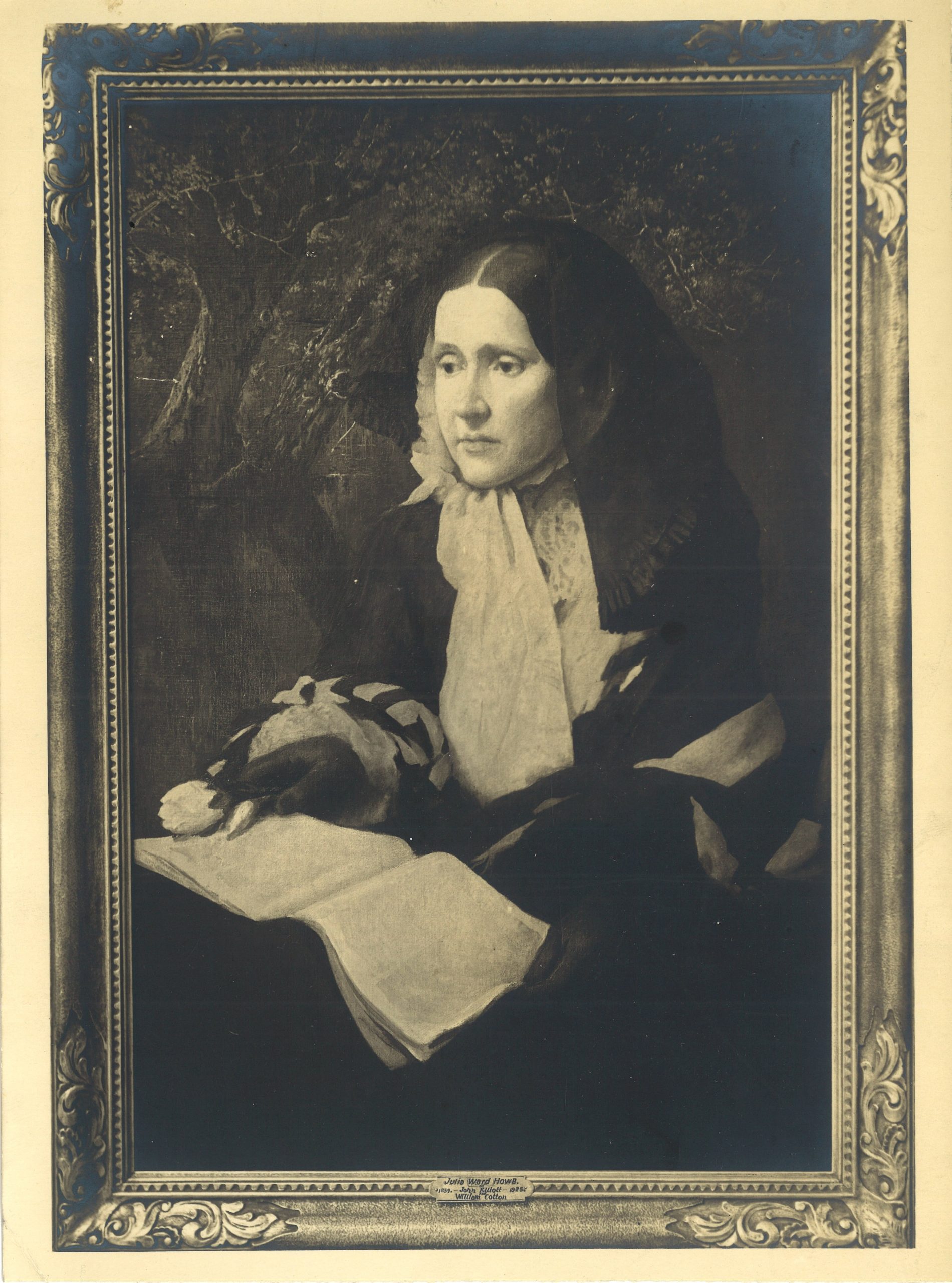

One of these Rhode Island women was Julia Ward Howe. Born in 1819, she had established a reputation as an abolitionist, writer, and poet before the Civil War broke out. Living in New York, her connection to Rhode Island was through spending summers with her family in Newport. She later owned an estate in Portsmouth, where she died in 1910. Her husband, Samuel Gridley Howe, was a physician. Together, they worked on abolitionist causes and were part of a group that supported abolitionist John Brown, known for leading an 1859 raid on a federal armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, with the intention of starting a slave liberation movement. During the War, the Howes provided financial support and service to the U.S. Sanitary Commission. In November of 1861, in Washington D.C. on Sanitary Commission business, the Howes visited a military encampment. On the carriage ride home, they and a friend traveling with them sang popular army songs—one being “John Brown’s Body,” after the aforementioned abolitionist. Julia Ward Howe was inspired to write new words to the hymn. She took some of her inspiration from the women she saw participating in the War. In her personal memoirs, she writes, “I thought of women of my acquaintance whose sons or husbands were fighting our great battle; the women themselves serving in the hospitals or busying themselves with the work of the Sanitary Commission.”1Frank J. Williams and Patrick T. Conley, The Rhode Island Home Front In the Civil War Era. Nashua, New Hampshire: Taos Press. 2013: 152-153 Her words were published in the February 1862 issue of Atlantic Monthly under the now well-known title “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”2Listen to “Battle Hymn of the Republic” [link]

Women during the Civil War also carried out intricate daily economic dealings, sustaining large families and businesses that, prior to the War, had been handled by the male heads of household. For example, Mary Saunders Johnson Blake, living in what is today downtown Providence, Rhode Island, did a staggering amount of work to bring in income for her large home during the absences of her son and husband. She managed a “sizeable flock of hens,” harvested a cherry tree, collected rent from a property she owned, saw to repairs at a shop her family-owned, took care of paying the workers who helped around the house, and would cook up to 20 pies at a time, often many times a week.3This is from the summary of the material written by Alys F. Mcleod on behalf of the Rhode Island Historical Society on April 18, 1998. Mary Saunders Johnson Blake, Mary Saunders Johnson Blake diary 1863, Manuscript, Robinson Research Center, Providence, RI Because we have access to her diary, we catch a glimpse into the life of one of many women who did similar things for their own families during the War.

Rhode Island women’s efforts did not stop in the home. During the Civil War, they also fought for political change. Elizabeth Buffum Chace called community members together in Providence for the abolitionist cause, brought pro-abolition lecturers to speak, sent out pamphlets, and encouraged her children to gather signatures for an anti-slavery petition. She was one of many who pressured President Lincoln to make abolition an aim of the war. It was relatively common for women, especially of upper-middle-class families, to be politically active while the war raged on from 1862-1865. In addition to the abolition of slavery, a major issue throughout the War, women like Buffum Chace and other well-known national political figures like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton also fought for voting rights for women and temperance.4Judith E. Harper, Women During the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. 2004: 3

Women across the Union volunteered to care for sick and wounded soldiers at military hospitals. One such hospital was authorized to open in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, on May 19, 1862. The small Marine Hospital in Providence had been overrun by the sick and dying coming off the battlefield, and the city desperately needed aid. Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital was determined to be the ideal place for a new high-capacity war-time hospital. It was located along a large wharf and had a railway depot, which meant that soldiers and medical supplies could be moved in and out more quickly than they could in Providence.5Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death At Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2012: 14 Female nurses from the surrounding townships, like Newport, made up a sizable portion of the volunteer workers at Portsmouth Hospital. One significant woman at the hospital in charge of those volunteers was Katherine Prescott Wormeley. Born to a wealthy English family in 1830, Wormeley moved to Newport with her mother at the age of 31 after the passing of her father. After the war broke out, she wasted no time in joining the U.S. Sanitary Commission’s Hospital Transport Service, which transported wounded soldiers around the East Coast. Aboard the Daniel Webster, a Union transport vessel, she cooked, bathed patients, and organized supplies. Before long, she moved on to a hospital in Virginia, where she learned hospital administration from her colleagues. Described by historian Frank Grzyb as being intelligent, possessing foresight, and having a “clear-thinking” mind, she was ready to “excel

in a field dominated by males.” It was no surprise then that by 1862 she had been appointed the “Lady Superintendent” of Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital. This position placed her in charge of staffing the hospital, managing the needs of the patients, overseeing the diet kitchen, and supervising the laundry department (which was no small feat considering almost 1,800 pieces of clothing needed to be washed every week). After a year of service at Portsmouth Grove Hospital, Katherine Wormeley stepped down from her position as Superintendent for health reasons, but not before leaving behind a legacy of unsurpassed organization and patient care that “would resonate for the remaining years of the hospital’s existence.”6Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death At Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2012: 80-857Read more about Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital in our essay [link]

Women all over the state provided the Union army with homemade equipment that helped them stay warm, comfortable, and healthy on the battlefield. In churches and homes, women spun cloth, made candles, sewed shirts, and polished boots for the soldiers in the field, often with their own money. Through ladies’ aid societies such as the Ladies Humane Society, they worked long, hard hours on top of their own personal commitments to ensure that the army was well-provisioned.8Association for the Relief of Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors in Washington, Manuscript, Charles N. Talbot Papers, Robinson Research Center, Providence, RI

As men went off to war, women took up work at home, manufacturing the resources the Union needed for victory, discussing the politics of the time, and continuing to support their families and feed their children.

Terms:

Homefront: spaces where battles are not happening during a war or military conflict and where civilian members of a population at war undertake activities that support the war effort

Conscientious: to do what’s right. to do one’s work or duty well and thoroughly

Abolitionist: a person against the institution of slavery

U.S. Sanitary Commission: a commission founded during the 19th century interested in the reform and maintenance of United States Hospitals

Temperance: the temperance movement was a social movement in the early 20th century in the U.S. to ban the consumption of alcohol

Well-provisioned: supplied with enough equipment, food, water to have all one needs to survive

Questions:

Why do you think that so many of the records we have today about the Civil War are only about the activities of men?

Think about the day-to-day lives of the women depicted in the essay. What would it have been like to be in their shoes?

Which Rhode Island woman were you most impressed by and why?

- 1Frank J. Williams and Patrick T. Conley, The Rhode Island Home Front In the Civil War Era. Nashua, New Hampshire: Taos Press. 2013: 152-153

- 2Listen to “Battle Hymn of the Republic” [link]

- 3This is from the summary of the material written by Alys F. Mcleod on behalf of the Rhode Island Historical Society on April 18, 1998. Mary Saunders Johnson Blake, Mary Saunders Johnson Blake diary 1863, Manuscript, Robinson Research Center, Providence, RI

- 4Judith E. Harper, Women During the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. 2004: 3

- 5Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death At Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2012: 14

- 6Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death At Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2012: 80-85

- 7Read more about Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital in our essay [link]

- 8Association for the Relief of Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors in Washington, Manuscript, Charles N. Talbot Papers, Robinson Research Center, Providence, RI