Teacher Background: Jewish History in Rhode Island

Essay by Holly Snyder 1Holly Snyder was the North American History librarian at the Brown University Library. She earned her Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and was previously a post-doctoral fellow in Modern Jewish Studies at Hampshire College. 2Funding for this chapter was provided in partnership with the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities through the National Endowment for the Humanities “A more perfect union” initiative.

According to local legend, the first Jews in Rhode Island may have been freemasons who arrived in 1658. 3 This legend originated with claims made about a single document with conflicting dates that referred to different calendar years, and it could not readily be made available for study at the time the claim was made in the 1800s. The document has not been seen by any researchers for the past century. The story also cannot be verified by information in any official records of the Rhode Island colony, or by any other private sources from the time that are still available to view. For further details about the document, see Samuel Oppenheim, “The Jews and Masonry in the United States Before 1810,” 19 Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (1910), pp. 9-14. While we cannot confirm that legend as fact, Jewish Rhode Islanders do appear in two important early events. The first was the establishment of the Jewish burial ground in Newport. The town property records show that this burial ground was established in February of 1678. 4Britain was one of the last European nations to complete its switch to the Gregorian form of calendar (the calendar that we still use today) from the older and inaccurate Julian form of calendar. If you find an old document from the 1600s or 1700s dated with two years (for example, “1677/78” or “1677/8”) it is from a period before the switch to the Gregorian calendar was completed and both calendars were in use at the same time. By our current standard, the year is correctly interpreted as the later of the two years. That is to say, “1677/78” should be understood as meaning 1678. The second was a 1684 petition to the colony’s General Assembly by seven Jewish merchants whose property had been seized by the colony’s tax collector. 5John Russell Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. III, p. 160. The description of the latter case makes clear that the seven Jewish merchants both claimed to be and were officially recognized by the General Assembly as residents of Rhode Island. Between the 1680s and the 1800s, there are many official records that show Jewish people were a part of Rhode Island. Here they lived, worked, and practiced their religion freely.

In 1636, Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, and other religious dissenters founded Rhode Island. They had their own religious beliefs, different from those of the Puritans in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Rhode Island was meant to be a safe haven for people with diverse religious ideas. Roger Williams was especially passionate about separating the government from religion. In his view, each person should have the liberty to follow their own beliefs without government interference. In Massachusetts and Connecticut, however, Puritan leaders controlled the government and frequently punished those who did not adhere to Puritan practices. In Roger Williams‘ view, such punishments forced the Puritan religion on people in a way that “stinks in God’s nostrils” (was offensive to God). He imagined a different course for Rhode Island. Roger Williams wanted Rhode Island to be a place where religious freedom was a basic principle of public life . However, upon Rhode Island’s founding in the 1630s, there were no Jewish people among its founders. How would these ideas be applied to Jews who arrived later, many years after the colony had been founded? 6 For more information about Roger Williams please see our Encompass unit

Early Jewish Settlement in Rhode Island

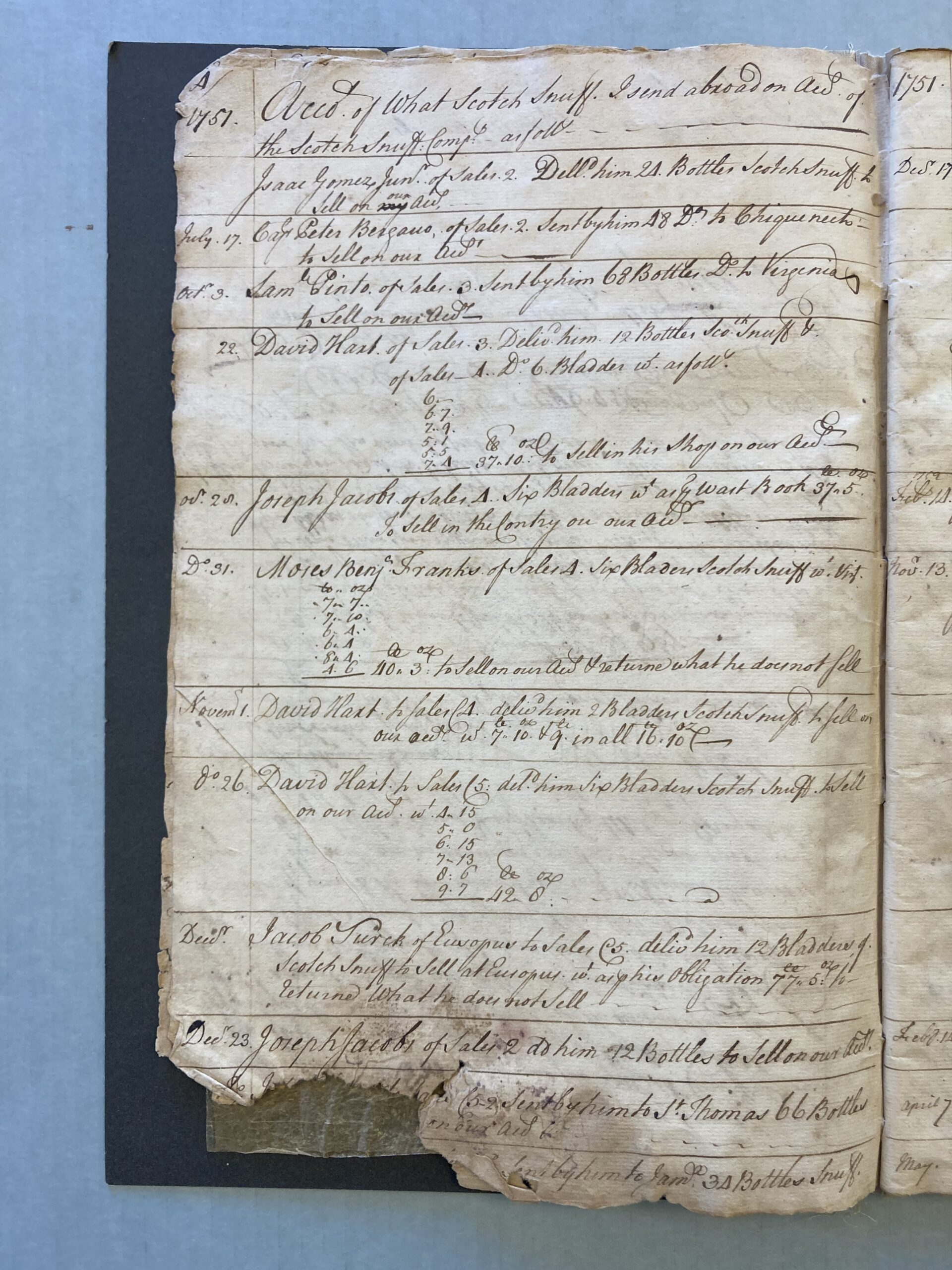

Similar to other parts of British North America, the growth of cities played a key role in the establishment and growth of Jewish colonial settlement in Rhode Island. Jews were attracted to Rhode Island by trade. Newport, in particular, was appealing for its growing prominence as a trading center during the 1670s. When Jewish settlers arrived in Rhode Island, they found a welcoming economic environment for the type of business activities they wanted to pursue. They bought and sold goods, and also manufactured items for sale. Manufactured items included potash, flavored snuff, rum-based liqueurs, and candles made from whale oil, for which they found a ready stream of buyers. Jewish merchants stayed and established homes, shops, warehouses and workshops, and invited extended family to join them.

The first group of Jews to settle in Rhode Island came from Barbados. They were determined to stay and practice their religious traditions, as demonstrated by their establishment of consecrated burial grounds according to Jewish customs. At the beginning, there was such strong support for this decision to build a Jewish community in Newport that when the group of merchants were seen as outsiders rather than English subjects, they fought back by petitioning the colony’s government. The petition, submitted by seven Jewish merchants to the General Assembly in 1684, was the earliest test of the colony’s commitment to religious tolerance. Ultimately, the General Assembly ruled that Jews should have the same freedom as other Rhode Island residents to live and worship as they wished as long as they followed the colony’s laws.

Although Jews living in Rhode Island had been granted the right to worship freely, they still faced anti-Jewish bigotry. . Jewish Rhode Islanders were often seen as having European roots. That perception gave Jews some legal and social privileges that were denied to peoples of Indigenous and African descent, many of whom were enslaved at this time. Many non-Jewish people in Rhode Island worked closely with their Jewish neighbors and treated them as friends, if not entirely as equals. But there were always a few who believed that Rhode Island was meant only for Protestant Christians and that Jews did not belong here.

These opponents tried to limit the rights of Jews economically, politically, socially, and religiously. While they did not propose that Jews should be banned from Rhode Island, they did succeed in placing some limitations on the rights of Jewish Rhode Islanders. These limitations prevented Jews from achieving true equity with their European neighbors in the colony. Such discrimination against Jews in Rhode Island continued even after the colony declared its independence from Great Britain. This was frustrating to those in the Jewish community who had been very loyal to the new state throughout the Revolutionary War, when Rhode Island was occupied by the British. It also prompted the Jewish community to pay special attention to the Constitution of the United States, which they praised in a letter to George Washington. But it took until 1798, nearly ten years after the United States Constitution was fully in effect, for the state of Rhode Island to finally change the discriminatory laws against Jews and grant them equal legal rights.

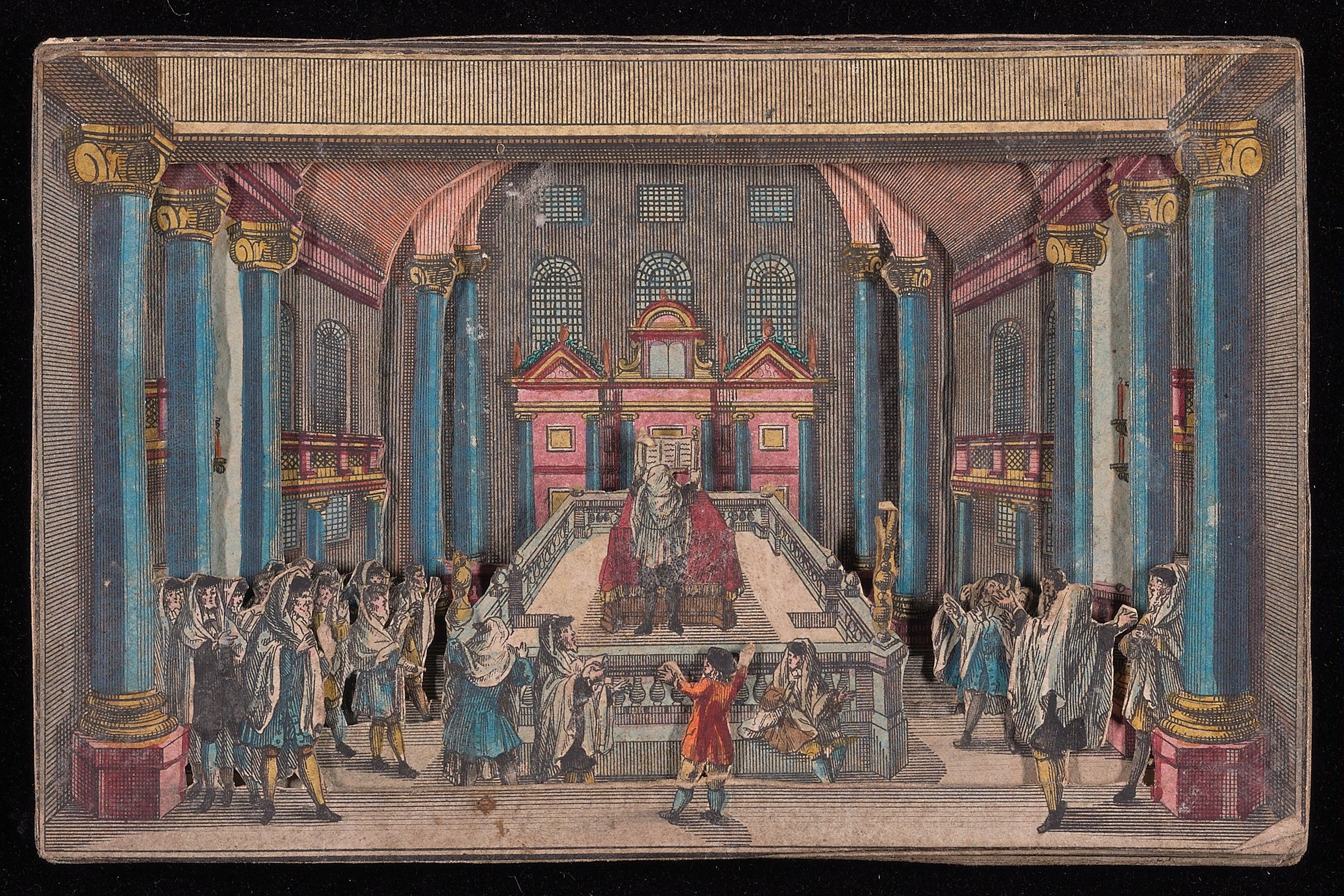

By the 1750s, Newport, Rhode Island, had a growing number of Jewish families, and a strong Jewish community began to form. This community worked to hire lay leaders and others with the right knowledge to serve the religious needs of Jewish life. They began to raise funds for the construction of a synagogue building to be located near the burial ground established in 1678. Although this effort took a long time, in December 1763 the Touro synagogue was consecrated and joined Newport’s architectural skyline. The newly constructed synagogue was a symbol of the religious diversity present in the city and throughout the colony. [For more information about Touro Synagogue, please see our Encompass essay[/mfn]

![“To the President of the United States of America Sir: Permit the children of the Stock of Abraham to approach you with the most cordial affection and esteem for your person & merits and to join with our fellow Citizens in welcoming you to New Port. With pleasure we reflect on those days—those days of difficulty and danger when the God of Israel, who delivered David from the peril of the sword, shielded your head in the day of battle: and we rejoice to think that the same Spirit who rested in the Bosom of the greatly beloved Daniel enabling him to preside over the Provinces of the Babylonish Empire, rests and ever will rest upon you, enabling you to discharge the arduous duties of Chief Magistrate in these States. Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now (with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events) behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language, equal parts of the great governmental Machine: This so ample and extensive Federal Union whose basis is Philanthropy, Mutual Confidence and Publick Virtue, we cannot but acknowledge to be the work of the Great God, who ruleth in the Armies Of Heaven and among the Inhabitants of the Earth, doing whatever seemeth him good. For all the Blessings of civil and religious liberty which we enjoy under an equal and benign administration, we desire to send up our thanks to the [Ancient] of Days, the great preserver of Men—beseeching him, that the Angel who conducted our forefathers through the wilderness into the promised land, may graciously conduct you through all the difficulties and dangers of this mortal life: and, when like Joshua full of days and full of honour, you are gathered to your Fathers, may you be admitted into the Heavenly Paradise to partake of the water of life, and the tree of immortality. Done and Signed by Order of the Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island Moses Seixas, Warden August 17, 1790](https://encompass.rihs.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/us0121_02_group_725-666x1024.jpg)

In Providence, Rhode Island’s other emerging urban center, Jewish settlement happened later. This was mainly because of slower economic development in the northern portion of the colony and because Providence was farther from main seaports along the coast. While a few Jewish merchants started businesses in Providence in the mid-1700s, there was not enough business to allow them to support their families. These pioneering merchants in the 1700s typically struggled to build business for a year or two, but then decided to move on to places with better opportunities including New York, the Caribbean, or Europe.

The Industrial Revolution and Jewish Contribution to Textile Production

The way the Jewish community previously grew and shrank started to change when the Industrial Revolution began in the 1800s. This transformation was made possible by improvements in machine technology. Initially, manufacturing was performed mostly in the northern part of Rhode Island. In this region, water power was readily available from local streams and rivers. The large-scale production made possible by harnessing water power led to the rapid growth of manufactured goods (textiles or fabrics, metals, metal work and machine tools). Industrialization gave workers steady jobs and allowed business owners to bring in good profits. Jewish immigrants were particularly drawn by the new opportunities to turn their knowledge of textile trading to the manufacturing of textiles. For example, Edgar J. Lowenstein learned silk manufacturing at the prestigious silk mills of Paterson, New Jersey. He then bought the Oriental Mills building in Providence and established the American Silk Spinning Company in 1908. The business did well, and he was able to send both his sons to Brown University. Other Jewish immigrants worked in cottons and woolens, or in the specialized manufacture of unique narrow fabrics. Narrow fabrics were used to create flexible tubing for gas appliances, elastic braiding and shoelaces.

In the 1840s, the stream of workers attracted to Rhode Island by these opportunities included Jewish immigrants from Western Europe. 7 The principal places of Jewish immigration from Western Europe were Germany, Holland, England and Austria. From Eastern Europe, the principal places of immigration were Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Russia. Later on, Jews from Eastern Europe arrived in Rhode Island. By 1854, Providence had an established Jewish community with its own synagogue called Congregation B’nai Israel (Sons of Israel). A second congregation, Sons of David, formed a few years later. 8These two early Providence congregations merged in 1874, and became Congregation of the Sons of Israel and David. The merged congregation built the Friendship Street synagogue, the first synagogue building to be constructed in Providence, in 1890. The congregation has since moved twice, but survives today as Temple Beth-El. Soon, Jewish community life began to develop in other parts of the state. Smaller Jewish communities with their own institutions were formed in other industrialized towns like Woonsocket and Bristol. Woonsocket was one of the earliest places in Rhode Island where textile factories were built. In Bristol, the United States Rubber Company set up manufacturing in 1901. Even though it did not have industrial opportunities to draw Jewish immigrants, Jewish life in Newport was also revived. In 1881, a group of Eastern European Jews petitioned to use the Touro synagogue. Touro had been closed since 1822 when Moses Lopez, the last Revolutionary War era Jewish resident of Newport, left for New York City. The congregation this new group established there has been at Touro synagogue ever since

As manufacturing in Rhode Island continued to grow and become more diverse, Jewish immigrants found the state an increasingly appealing place to build a better life for their families. In the effort to create communities, Jewish immigrant families built not only cemeteries and synagogues, but also a wide variety of institutions designed to serve their social needs in the 1800s and 1900s. These institutions included charitable organizations, burial societies, lending institutions, cultural activity centers, clubs, recreational facilities, and kosher markets. While some of these institutions have faded away with time, many are still active. Nevertheless, all serve as important markers of Rhode Island’s Jewish history.

Terms:

freemasons: The name given to members of various fraternal (men’s) organizations whose activities originated from medieval guilds

Puritans: In the 1600s, some English Protestants believed that the practices of the Church of England were too much like those of the Roman Catholic Church. They called themselves “Puritans” and defied the authority of the clergy because they thought they were corrupted by the power they held.

religious dissenters: In the 1600s and 1700s, anyone in England who belonged to a church other than the official Church of England was called a dissenter because they had different ideas about religion that the official Church allowed.

consecrated: A process by which something (typically a building or land designated for use as a church, temple or burial ground) is removed from ordinary activities and dedicated solely for religious use by means of prayers, rites and/or ceremonies.

Questions:

What are reasons different groups of people come to a new place? What examples do you see?

How have people in the past built community? How are those ways different or similar to how we build community today?

- 1Holly Snyder was the North American History librarian at the Brown University Library. She earned her Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and was previously a post-doctoral fellow in Modern Jewish Studies at Hampshire College.

- 2Funding for this chapter was provided in partnership with the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities through the National Endowment for the Humanities “A more perfect union” initiative.

- 3This legend originated with claims made about a single document with conflicting dates that referred to different calendar years, and it could not readily be made available for study at the time the claim was made in the 1800s. The document has not been seen by any researchers for the past century. The story also cannot be verified by information in any official records of the Rhode Island colony, or by any other private sources from the time that are still available to view. For further details about the document, see Samuel Oppenheim, “The Jews and Masonry in the United States Before 1810,” 19 Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (1910), pp. 9-14.

- 4Britain was one of the last European nations to complete its switch to the Gregorian form of calendar (the calendar that we still use today) from the older and inaccurate Julian form of calendar. If you find an old document from the 1600s or 1700s dated with two years (for example, “1677/78” or “1677/8”) it is from a period before the switch to the Gregorian calendar was completed and both calendars were in use at the same time. By our current standard, the year is correctly interpreted as the later of the two years. That is to say, “1677/78” should be understood as meaning 1678.

- 5John Russell Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of Rhode Island, Vol. III, p. 160.

- 6For more information about Roger Williams please see our Encompass unit

- 7The principal places of Jewish immigration from Western Europe were Germany, Holland, England and Austria. From Eastern Europe, the principal places of immigration were Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Russia.

- 8These two early Providence congregations merged in 1874, and became Congregation of the Sons of Israel and David. The merged congregation built the Friendship Street synagogue, the first synagogue building to be constructed in Providence, in 1890. The congregation has since moved twice, but survives today as Temple Beth-El.